The comet of the century is dead

Much attention has been payed lately to the novice comet C/2012 S1, more widely known as comet ISON. At the crest of the wave, it was even said that the integrated brightness of the comet after the perihelion could exceed that of the full moon. It was nicknamed “the comet of the century” and everybody from professional and amateur astronomers to mass media was waiting for the magical date as a test for our wildest dreams. However, as it is currently well known, the comet was unable to survive its close pass around our star. We always knew that it was possible but wanted to imagine yet another beautiful comet in the sky. At this point, I think it is a good exercise to look for the scientific literature and see how it covered the comet from its discovery to its mostly certain death.

Comet C/2012 S1 was discovered on September 21, 2012 by Vitali Nevski and Artyom Novichonok. They were using a 16” telescope which is part of the International Scientific Optical Network, hence its name. Several circulars detailed the discovery and subsequent determination of the cometary orbit. The comet was then identified as a “sungrazer” or a comet with a pass very close to the Sun at less than 3 times the solar radius, expected on November 28, 2013. This gave a year of especulation, something very unusual for sungrazers, at a time when we have a plethora of space-based solar observatories able to document its evolution with unprecedented detail.

In a paper published in October, Knight and Walsh 1 tried to answer in advance the question that was in everybody’s mind: will it survive such a close perihelion? This depended on many unknown or poorly constrained parameters. Most importantly, Hubble Space Telescope observations had placed an upper limit for the size of the comet at 2km, big enough to survive tidal disruption. The lower limit, determined by gas emissions, was 0.4 km, just in the bottom end for a likely success. Other important factors were for example the shape and rotation (sense and period). Using simulations of N-bodies aggregates with a parabolic flyby, Knight and Walsh were moderately optimistic with respect to the survival of the comet. However, other work by Samarasinha and Mueller 2 pointed that changes in the rotation of the body could happen in viccinity of the Sun due to outgassing and tidal torques. Those changes could be fatal for the destiny of our Solar System traveller. More observations were clearly needed in order to characterize the evolution of the comet closer to the D-day.

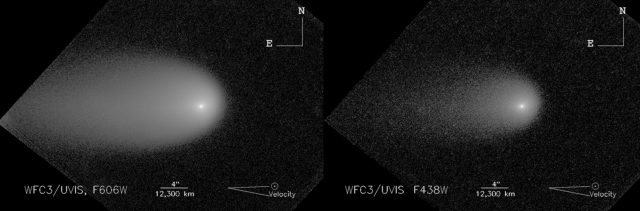

Using far-infrared to millimeter observations from Herschel Space Observatory and Institut de Radioastronomie Millimétrique (IRAM) in March and early April 2013, Rourke and collaborators 3 were able to establish an upper limit to the H2O outgassing, detected the production of CO and showed a first characterization of dust production rates. When such results in press, lower values were retrieved pointing to a decrease in the comet activity. Hubble Space Telescope observations reported by Li et al. 4 showed the nucleus to be smaller than expected and also provided valuable information on the particle size distribution and color, apart from other clues on the nucleus rotation.

A decreased activity was confirmed 5 by June 2013 by using a variety of ground-based telescopes from the 8-m sized Gemini North on Hawaii to the more modest 1.23m telescope at Calar Alto observatory (Spain). It was then thought that the activity through the first semester of the year might had been dominated by the loss of a highly volatile layer.

As the comet approached the perihelion the activity increased again and the community started feeling optimistic, though cautious, again. Thanks to the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory we were able to see the Sun flyby on November 28, 2013. After a few days of confussion it was mostly clear that the nucleus had been disrupted and nothing more than a cloud of dust was left. By the time of this writing it is generally accepted that the comet ISON is dead, after all. The famous comet hunter David H. Levy once said “Comets are like cats: they have tails and they do precisely what they want”. And so did the comet of the present story. It was small and brand new so, in fact, this fate was not completely unexpected.

But, did anybody warned against this possibility clearly? At least one scientist did, to tell the truth. In a report submitted to arxiv on October 2, 2013, Ignacio Ferrin from University of Antioquia (Colombia) predicted that ISON would not survive the perihelion 6. He argued that the brightness evolution of the body, by comparison to other previous cases, was unequivocally telling us that this was going to happen. And he was right, as we all saw.

These months have been very intense. There was a feeling that something important and beautiful could happen in our skies. This excitation was passed on to the society through newspapers and media. It finally did not happen but I’d like to think that this made a lot of people wonder a little bit on the wonders of Universe. And that’s good, even if we won’t have a huge comet in the heavens by Christmas.

References

- M.M. Knight and K.J. Walsh (2013), “Will comet ISON (C/2012 S1) survive perihelion?”, The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 776:L5, doi:10.1088/2041-8205/776/1/L5 ↩

- N.H. Samarasinha and B.E.A. Mueller (2013), “Relating changes in cometary rotation to activity: current status and applications to comet C/2012 S1 (ISON)”, The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 775:L10, doi:10.1088/2041-8205/775/1/L10 ↩

- L.O. Rourke et al. (2013), “Herschel and IRAM-30 m observations of comet C/2012 S1 (ISON) at 4.5 AU from the Sun “, Astronomy & Astrophysics 560, A101, d.o.i.: 10.1051/0004-6361/201322756 ↩

- K.J. Meech et al. (2013), “Outgassing behavior of C/2012 S1 (ISON) from September 2011 to 2013 June”, The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 776:L20, doi:10.1088/2041-8205/776/2/L20 ↩

- J.-Y. Li et al. (2013), “Characterizing the dust coma of comet C/2012 S1 (ISON) at 4.15 AU from the Sun”, The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 779:L3, doi:10.1088/2041-8205/779/1/L3 ↩

- Ignacio Ferrin (2013). The Impending Demise of Comet C/2012 S1 ISON, arXiv: 1310.0552v2 ↩

1 comment

[…] con los cometas que se acercan por primera vez al Sol, su destino ha resultado ser muy diferente. Aquí podéis ver la entrada que he escrito recientemente para el blog Mapping Ignorance, iniciativa de […]