Do you take sex into account?

Yes, I talk to you, even more if you are one of those scientists working with any living being either unicellular or multicellular with sexual dimorphism seared in their chromosomes. Such a question may seem trivial. However, recent findings suggest that it is not so trifling, and that an affirmative answer could have major implications not only in experimental results but also in the health of the people receiving the benefits of those results. On one side, we find the fact that most studies to date using either cell lines or animal models suffered negligence: the sex of the subjects under study has been either neglected or shifted towards one gender excluding the other, mainly excluding females. The reasons for this were mostly assumptions probably not as solid as they should. Now, those assumptions have been proven false and the NIH raises again a hue and cry. On the other side, it has been found that it seems important not only to consider the gender of laboratory animals but also the gender of the experimenter in order to trust the data.

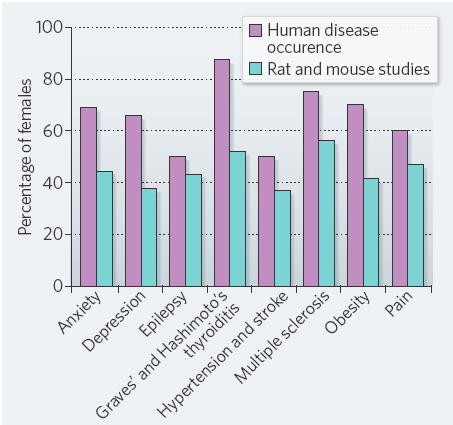

The exclusion of female test subjects in neuroscience and biomedical research was based in the belief that they are more variable due to the hormonal changes during the estrous cycle and therefore, any result would be unreliable. It was assumed that, to trust the experimental result obtained with female animals, it would be necessary to repeat any experiment in the different parts of the menstrual cycle. That was, first expensive and second time consuming. Therefore, most of the experiments, including the ones contributing to develop and test the drugs we have today whiting our hands, were done in populations of mostly male animals. It was also held that apart of the reproductive differences, the cells of males and females were equal when concerning about molecular processes and mechanisms. But the fact (known already for long) is that the secondary non-desirable effects of many drugs and treatments are more prevalent and serious among women than men.

Moreover, the isolated effect of the sexual chromosome complement XX / XY is being investigated in recent times. It has been demonstrated that male and female cells basic behavior is essentially different in many cases. For example, to rule out that differences in cell behavior are due to hormonal presence, primary cells from mice prior sexual differentiation and hormonal presence were used1. It was found that those female and male cells (never exposed to hormones) respond to stress in different ways. They were also different in basal gene expression and the addition of exogenous sex hormones altered the response to stress differently depending the hormone used.

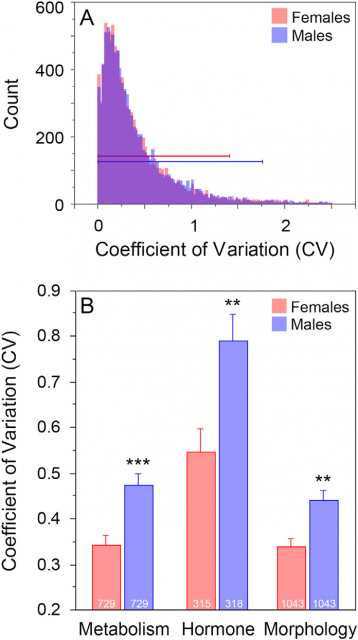

Furthermore, in an effort to overturn the belief against use females in biomedical experiments, Prendergast and coworkers2 did a meta-analysis testing the female and male mice variability across 293 articles compressing the study of behavioral, morphological, physiological and molecular traits. Importantly, the females in those works were studied without taking into account its estrous cycle state. And thus, the main outcome of that meta-analysis was rather surprising: females are not more variable than male but for some traits like metabolism, hormones and morphology males are more variable (Fig.2). As it is known that the group housing condition (versus isolation) is cause of variability in male mice (due to territorialism and fight), they checked whether this was the cause for not find differences in variability respect females. Finding also a striking thing: group housing increased the variability the same extend in males and females, letting then the male variability unexplained. But not only that, there was another worrying point: more than half of those 293 papers did not have any reference about how the mice were housed. This work, together with other extensive study about pain-associated traits in mice (Mogiland and Chanda, 2005), strongly argues in favor of including regularly female experimentation animals in research.

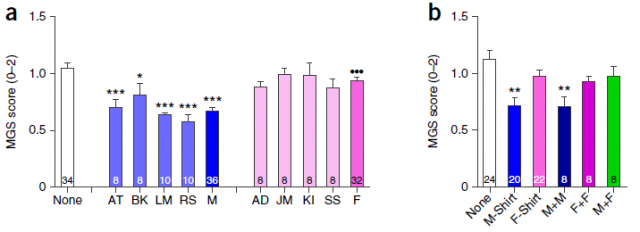

Additionally to the worrying amount animal studies lacking housing details, an article in Nature early last summer points that the experimenter sex can affect mice and rats responses in behavioral testing and thus impacting experimental results3. They report pain inhibition and decrease in pain behavior (via stress-induces analgesia) in mice and rats in presence of male experimenters or T-shirt worn by men. The pain inhibition was not significantly different to the controls in presence of female experimenter or T-shirt worn by females (Fig. 3). In what seemed an olfactory response, the nesting material from other unfamiliar (to the mice under test) mammals like mice, guinea pigs, rats, cats and dogs produced more pain inhibition if the material was from male than from female. In the pheromone trials that they did discard single-pheromone action, betting more by the effect of shared odorant cocktails across mammalians. To note, they also found that the sex of the experimenter is able to alter the threshold response to acute pain tests in large mouse sample sizes. That threshold was higher when the experimenter was man. Such a result talk about the significance of thoroughly describe the housing conditions to the detail of who did a given experiment in order to interpret accurately the results.

Hence, present here one of the Achilles heels of science (not just biomedicine and neuroscience): in this race there is no time or resources to waste if an assumption sounds quite logic. In this particular case, failing to take into account the sex in research is going to be a big problem. Despite the NIH has spent nearly twenty years begging for the equitable inclusion of female animal models in biomedical research due to the problems for generalizing epidemiological and clinical studies made on males to females, only a little progress has been done. Additionally, The widespread lack of data about housing conditions of the experimental animals also will be a problem to evaluate the results in neuroscience. The problem will be even bigger if it is confirmed that the sex of the experimenter distorts the animal behavior. Descending to the level of the cell culture experiments also seems that the gender of different strains has not been regarded when evaluating findings, which could leave lame also many conclusions drawn from cellular models. Works testing the “higher female variability” and gender impact in cellular processes have been rather late and scarce. But now, they begin to drop dissolving some logic assumptions like acid and revealing that maybe now we have to walk the road twice to know where we are. I hope examples like these with neglecting gender in biomedical research help us to be more thorough when performing is our task. Making an assumption, often, is the first step for error.

References

- Penaloza, C. et al. Sex of the cell dictates its response: differential gene expression and sensitivity to cell death inducing stress in male and female cells. FASEB J.23, 1869–79 (2009). ↩

- Prendergast, B. J., Onishi, K. G. & Zucker, I. Female mice liberated for inclusion in neuroscience and biomedical research. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev.40, 1–5 (2014). ↩

- Sorge, R. E. et al. Olfactory exposure to males, including men, causes stress and related analgesia in rodents. Nat. Methods11, 629–32 (2014). ↩

1 comment

[…] ¿Hasta qué punto influye el sexo en una investigación científica en biología? No solo el sexo de los especímenes, sino el de los investigadores. Y no nos estamos refieriendo a cuotas en los laboratorios, sino a efectos en los […]