Visions for blind eyes: the Charles Bonnet syndrome

Charles Lullin knew that the figures and people he was seeing were illusions.

It was 1759, Charles Lullin was almost ninety years old and he had lost most of his vision: he was still able to distinguish some objects but he was not able to read or write. A servant used to read him the newspaper every day. Despite the fact that he was almost blind, the visions were clear: a blue handkierchief floating in the air, a group of butterflies, two gentlemen’s walking in his room, etc. The visions were diverse and none of them emitted any sound: they were just images moving in front of his eyes.

He never though they were real and he just needed blinking to vanish the images. But, he was curious. The phenomena amazed him and he wanted to share it with others. That is the reason why he dictated his visions in an eighteen pages document and the testimony was signed by five people to certify that he was not mentally ill. The first was his own signature, and the last one was from a naturalist: his grandson, Charles Bonnet.

The Charles Bonnet syndrome is a condition characterized by the appearance of simple or complex hallucinations in patients with an impaired sense and conserved cognitive status. The most common are visual hallucinations with an impaired vision, but it has been documented cases with auditory hallucinations (when the patients have impaired audition instead of vision). The patients experience complex visual hallucinations with images of animals, persons and bizarre geometric forms; and this images can have unusual characteristics like a bigger or smaller size, branching forms, overlapping patterns, etc. The images can last seconds to hours and the duration of the episodes with the syndrome can be from days to years. Despite the visions, the patients have intact cognition and they can usually distinguish easily the “Bonnet´s images” from the reality, as the images have peculiar characteristics and they are viewed in finer details than real objects.

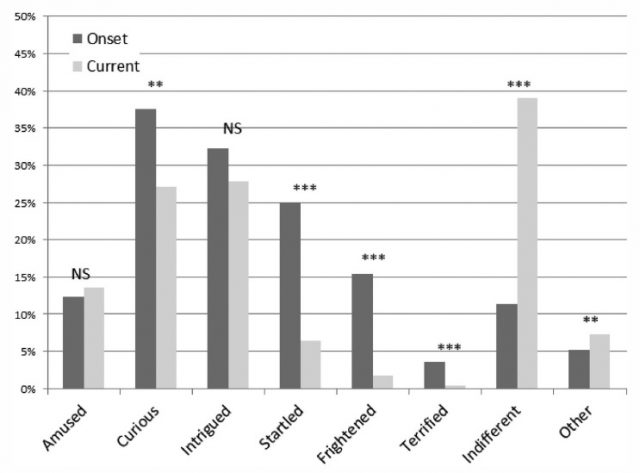

The prevalence of the syndrome ranges from 10-60% in patients with low visual acuity. The fear to be considered crazy it is one of the main reasons why patients do not usually explain the visions and it makes difficult to determine with precision the prevalence of the syndrome. Actually, despite the fact that the hallucinations are considered benign, around a third of the patients find the hallucinations themselves an unpleasant or disturbing experience. Fortunately, they are not usually frightening and once the patience has been diagnosed, he understands his situation and the negative response to the hallucinations becomes minimal.

Low visual acuity is the main risk factor to develop the syndrome, however some patients with normal vision have developed the syndrome if they have visual field alterations secondary to such neurological disorders, as those caused by certain cerebrovascular accidents or any other kind of brain damage. Additional risk factors are social isolation and age (the majority of patients are elderly with a mean age of 70 to 85 years).

Nowadays, there is not a clear explanation for the hallucinations in Charles Bonnet Syndrome. One of the most accepted theory suggests that vision loss leads to disinhibition in visual cortical regions. In theory, the disinhibition could generate the hallucinations since it would facilitate the generation of spontaneous firing of the visual cortical regions. Another theory is the release phenomenon, where missing input to primary visual areas would contribute to a release of visual hallucinations. For example: the loss of stimulation of retinal nerve cells, caused by any eye disease, decreases stimulation of the occipital cortex but since the patients are not completely blind, the stimulation does not disappear completely. The residual visual signals could create changes to synapses in an attempt to compensate for the limited stimulation transforming neurons into hyperexcitable cells. In both theories, the main idea is that the decrease in visual activity induce neuronal changes in the cortex which generate the hallucinations.

Since the hallucinations are benign, usually there is no need to treat the syndrome. However, at the begging the visions can generate stress, fear to be crazy, etc. So, it is important an early diagnosis and educate the patients to reassure them the benign nature of the hallucinations. Finally, since there is no current established medical treatment for the symptoms, threating the visual loss is usually the only option to treat the syndrome. Still, there are some case report where treatments with neuroleptics, anticonvulsants, antidepressants or cholinesterase inhibitors have had favorable results.

Charles Lullin knew that the images were mere illusions. Nowadays, more than two hundred and fifty year later, we do not know much more: we do not have any treatment or at least a unique and validated theory to explain the syndrome. But I am sure that with the new advances in neurobiology, we will know sooner than later (or at least before two hundred and fifty years more), why that man saw one day a blue handkierchief floating in front of his eyes.

References:

Cox, T. M., & Ffytche, D. H. (2014). Negative outcome Charles Bonnet Syndrome. British Journal of Ophthalmology, 98(9), 1236–1239.

Draaisma, D. (2012). Dr. Alzheimer, supongo. Editorial Ariel.

Santos-Bueso E, Serrador-García M, Sáenz-Francés F, García-Sánchez J. (2016) Síndrome de Charles Bonnet en paciente con alteración campimétrica y buena agudeza visual. Neurología. 31:208—209.

Vale, T. C., Fernandes, L. C., & Caramelli, P. (2014). Charles Bonnet syndrome: characteristics of its visual hallucinations and differential diagnosis. Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria, 72(5):333-336.