Restoring my voice

One of the worst things that can happen to someone that loves talking as much as I do is losing my voice. What to most people is just a temporary inconvenience -or a relief depending on who you ask- for some is a real hindrance. Patients that suffer from a permanent impairment to their ability to voice out their ideas usually have undergone repeated surgeries or radiation to remove cancerous and non-cancerous growths and, as a result, have a scarring or stiffening of their vocal chords mucosa that impairs their sound production.

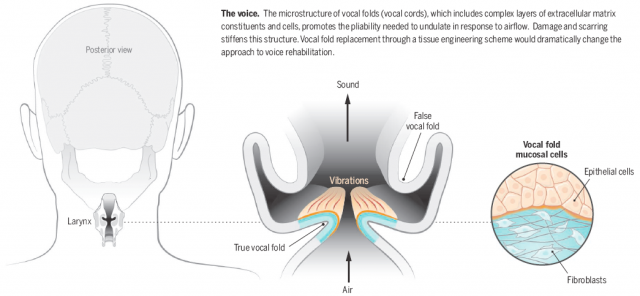

Our voice is the result of the vibration of the vocal chords inside the larinx, these are two flexible bands of muscle lined with a mucosa, a delicate tissue that resonates when the air passes through it.

An example of human vocal folds in action viewed using a strobe light. These dynamic tissues can vibrate hundreds of times each second, acting as a sound source for speech and song. Source: Nathan Welham, University of Wisconsin, Madison / Science News

For the first time, a team of scientists lead by Welham and Ling 1 and published recently in the journal Science Translational Medicine has been able to recreate vocal chord tissue from isolated cells from human vocal chords in vitro. The two cells types, the connective fibroblasts that make up the main body and the epithelial cells that cover the surface, were collected both from a cadaver and from live healthy samples from patients that had their vocal chords removed for unrelated reasons.

These two cells types were set to grow over a 3D collagen matrix that mimics the body conditions and after a couple of weeks the cells had developed into a complex structure that both anatomically and molecularly resembled the native vocal chords in vivo.

To test whether they were also functionally viable, they implanted one of this engineered vocal chord tissues into the larynx of dogs where one of the vocal chords was still the native, and they found that their resonation and sound produced, when air was pumped through, was almost as good as with the original tissue. Not only that, they also found out that their tissue produced no immune rejection in mice genetically modified to resemble the human immune system, therefore making this implants suitable for transplantation in the long term.

One of the biggest challenges of the technique is to assure functionality once transplanted into the recipient patient because, as mentioned in the comment to the article by Long and Chhreti in Science2, the vocal chords are subjected to many stresses like the strength of the air flow, bacterial infections or phonatory trauma, and these factors might affect healing after implantation and, therefore, functionality.

Even after consideration of these potential problems Ling et al.‘s technique offers a promising alternative for patients with a complete loss of vocal chord function and in the future could even be the method of choice for replacement right after resection after a cancer surgery.

All in all a new demonstration of the possibilities that in vitro organ development offers for the future of organ replacement.

References

- Ling C, Li Q, Brown ME, Kishimoto Y, Toya Y, Devine EE, Choi KO, Nishimoto K, Norman IG, Tsegyal T, Jiang JJ, Burlingham WJ, Gunasekaran S, Smith LM, Frey BL, Welham NV. (2015) Bioengineered vocal fold mucosa for voice restoration. Sci Transl Med. 7(314):314ra187. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aab4014. ↩

- Long JL, Chhetri DK. (2015) Restoring voice. Science. 350(6263):908-9. doi: 10.1126/science.aad7695. ↩

1 comment

[…] Perder la voz no es cosa baladí. Piensa en lo mal que lo pasas cuando no puedes hablar durante un par de días. Por eso es tan interesante que por primera vez se haya conseguido producir tejido de cuerdas […]