Exocomets

Comets are one of the key components of our Solar System, at least for the Earth’s evolution and humankind point of view. While the inner region of our system was depleted in volatiles due to the high temperatures close to the Sun, the left overs in the outer borders retained water and other condensables in the form of ices. Current models of Solar System formation and evolution show that the migration of the gas and icy giants finally conducted to what has been called the Late Heavy Bombardment, when many small bodies we can think of as comets, transported volatiles into the rocky inner planets, such as the Earth. Thus, we now have oceans filled with water that survived in the cool, outer Solar System and that could have not been kept at our home during the planet formation. Moreover, some speculate on the possibility that the complex organics we often see on asteroids and comets may also played a role on the apparition and evolution of life in our planet. In any case, it is obvious that we would not be the same if comets were not out there, acting as ‘dirty snowballs’ that enriched our vicinity with material that could have not survived otherwise.

We know up to date lots of planetary systems at different evolutionary stages. One of the most interesting ones is that of beta-Pictoris, a young A-type star at some 8000K at the star’s surface with a very young disk formed by dust and gas, some 10 million years old. This debris disk displays clues of planetary formation happening just now close to the star, while other, more subtle features warn us about other processes known only to have happened before in our Solar System. This is certainly an intriguing and amusing place to understand how things happened in the past, when our own planet was forming around the Sun.

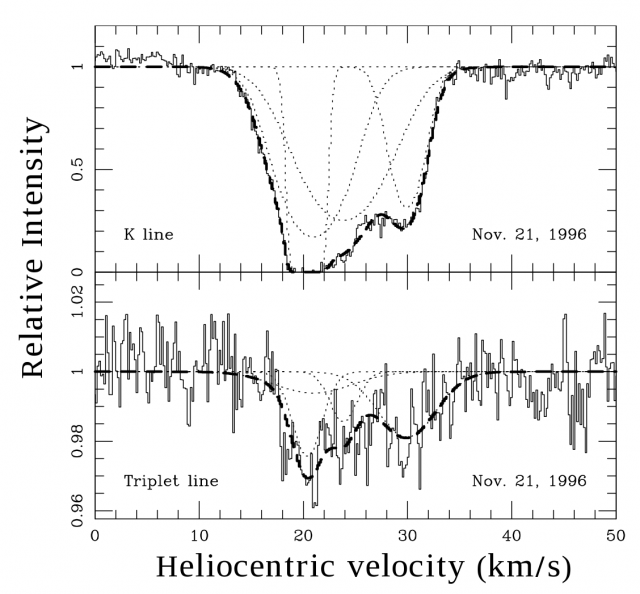

So, given that we have such a good information on beta-Pictoris disk, is it possible to find comets around this other sun? It certainly is, as it was shown around 1987 when we first witnessed some clues that strongly pointed to the presence of small objects traveling into the inner disk, resembling to what happened in our system during the Late Heavy Bombardment. Those clues were termed Falling Evaporating Bodies (FEBs) and were seen as redshifted absorptions at the K and H ionized Calcium lines (Ca II in the astronomical jargon). Among the many papers dealing with the observation and characterization of the FEBs, we can highlight the work by Beust and collaborators in 1990 1 and 1998 2 which provided a comprehensive basis in order to interpret the FEBs as the infalling of small bodies, mostly resembling the good, old comets we have in our Solar System (see Figure 2 for further information).

As good as the idea was, the detection of exocomets was mostly left apart for the following years. Some works were done and characterization of some circumstellar disks (HR 10 and HD 8905, 3) threw results similar to those in beta-Pictoris. In 2012, however, Sharon Montgomery and Barry Welsh published a work in PASP 4 showing that a number of young A-type stars with debris disks had many things in common, particularly the presence of FEBs or exocomets. With this work, up to seven systems were supposed to have exocomet activity (beta-Pic, HR 10, HD 8905, beta-Carinae, 49 Ceti, 5 Vulpeculae and 2 Andromedae). All of them were interpretable in terms of the same model (young disks showing infrared emission excesses and planetary formation inside them) as well as observed using the redshifted lines of ionized calcium absorption.

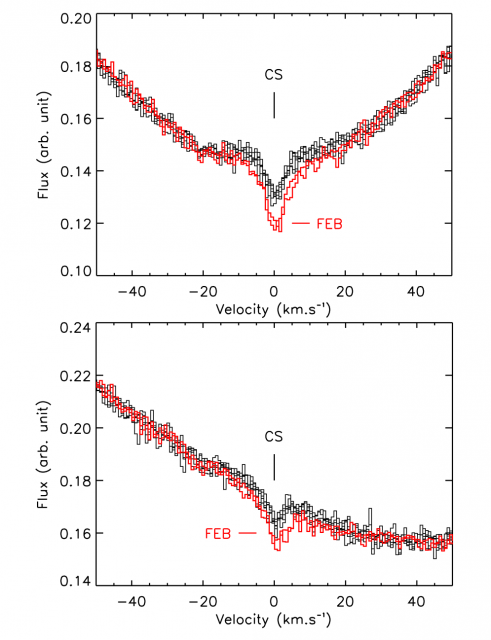

The most recent detection of exocomet activity has been published this year 5. HD 172555 is, guess what, an A-type star surrounded by a debris disk. Once again, the careful analysis of Ca II K and H lines showed the FEBs or exocomets. This work by Kiefer and collaborators used observations with high-resolution HARPS spectrograph at the 3,6m telescope in La Silla, Chile. The high sensitivity of the instrument allowed for the first time not only to detect much lower redshifts in the calcium absorptions, but also to isolate without any doubt absorptions of the circumstellar disk associated with the transient phenomena, therefore ensuring the detection of the exocomets.

All these works give us good perspective on how subtle our careful analysis of new born planetary systems can be. As stated above, the comets surely had a profound impact on our planet and it is really compelling that other planetary systems being born have comets, as well. We will probably know much more about this as our instruments get more precise. The degree of detail we already are capable of is certainly a good demonstration of the combined power of science and technology but it is by no means the best we are going to be able to do.

References

- H. Beust, A.-M. Lagrange-Henri, A. Vidal-Madjar and R. Ferlet (1990). The beta-Pictoris circumstellar disk. X. Numerical simulations of infalling evaporating bodies. Astronomy & Astrophysics, 236, 202 – 216. ↩

- H. Beust, A.-M. Lagrange, L.A. Crawford, C. Goudard, J. Spyromillo and A. Vidal-Madjar (1998). The beta-Pictoris circumstellar disk. XXV. The Ca II absorption lines and the Falling Evaporating Bodies model revisited using UHRF observations. Astronomy & Astrophysics, 338, 1015 – 1030. ↩

- B.Y. Welsh, N. Craig, L.A. Crawford and R.J. Price (1998). bet-Pic like circumstellar disk gas around HR 10 and HD 85905. Astronomy & Astrophysics, 338, 674 – 682. ↩

- S.L. Montgomery and B.Y. Welsh (2012). Detection of variable gaseous absorption features in the debris disks around young A-type stars. Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 124, 1042 – 1056. doi: 10.1086/668293. ↩

- Kiefer F., Lecavelier des Etangs A., -C Augereau J., Vidal-Madjar A., Lagrange A.M. & Beust H. (2014). Exocomets in the circumstellar gas disk of HD 172555, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 561 L10. DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201323128 ↩

2 comments

[…] [Leer la entrada completa en Mapping Ignorance] […]

[…] planeta-sistemaren baten? Erantzuna, EHUko Zientzia Planetarioen taldeko Santiago Pérez-Hoyosek Exocomets artikuluan azaltzen digun moduan, bai […]