Burial practices of Neanderthals and early humans in the Levant

Burial practices of Neanderthals and early humans in the Levant

A new study 1 by Professor Ella Been from Ono Academic College and Dr. Omry Barzilai from the University of Haifa sheds new light on the burial practices of Homo sapiens and Neanderthals in the Levant region during the Middle Paleolithic (MP).

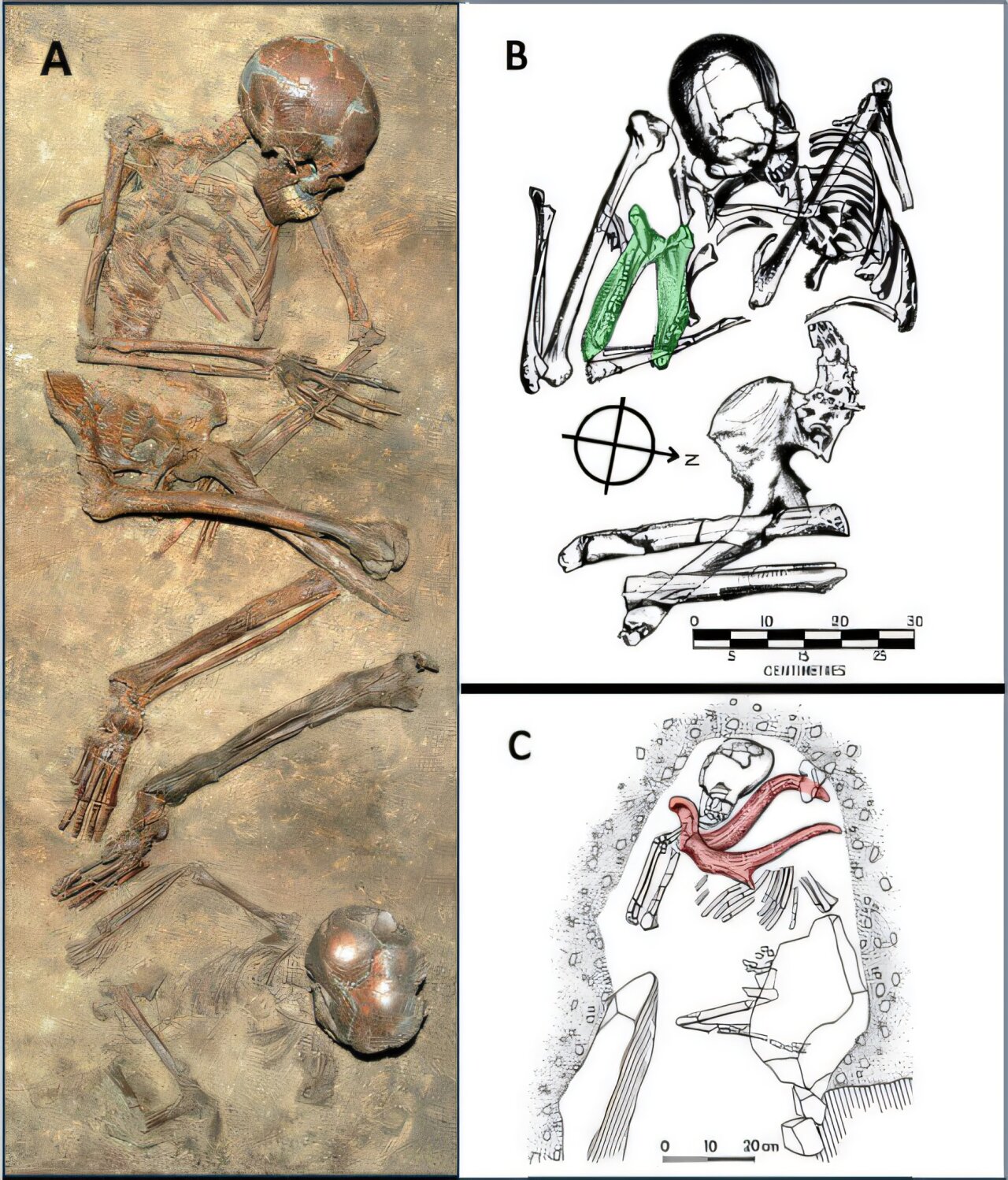

The research, which examined a total of 17 Neanderthal and 15 Homo sapiens burials from various archaeological sites, revealed both similarities and differences in how these two species treated their dead, including differences in burial location, body posture and specific grave goods.

The MP in Western Asia, specifically the Levant, is of particular interest in the study of human evolution due to the co-existence of two hominin species at this time. While Homo sapiens arrived in the region between 170,000 and 90,000 years ago and re-entered the region 55,000 years ago from Africa, Neanderthals came into the Levant from Europe around 120,000 to 55,000 years ago.

During this time, both species suddenly began burying their dead, something neither species had done before. This suggests that burials were first innovated in the Levant before spreading or being autonomously innovated elsewhere.

The two species are easily distinguishable based on their biology and morphology, with nearly every bone in the body being unique to either species. However, their material culture, mobility and settlement patterns are nearly indistinguishable. Despite this, it was hypothesized that the two species may have had different burial practices.

It was a Neanderthal burial which inspired the current study, says Prof. Been, “A few years ago, my colleague Dr. Omry Barzilai and I published an article about the Neanderthals from Ein Qashish (EQ3). Initially, we were uncertain whether EQ3, which was found in an open-air site, was a burial.

“This uncertainty sparked our interest in Neanderthal burial practices, particularly in the Levant. Our current research has led us to the conclusion that EQ3 was indeed a deliberate burial. Additionally, we believe that examining burial practices might provide insight into the similarities and differences between H. sapiens and Neanderthals.”

Based on the results of around 37 total confirmed burials, it was found that both Homo sapiens and Neanderthals buried their dead regardless of sex or age. However, Neanderthal infant burials were more common than Homo sapiens infants. Similarly, both species would sometimes include grave goods in the form of animal remains, including goat horns, deer antlers, mandibles and maxilla.

Despite these differences, the researchers also observed differences, indicating that not all aspects of H. sapiens and Neanderthal material culture were similar in the Levant as previously hypothesized.

Prof. Been elaborates on some of the differences observed, “In the Levant during MI6-MI3, we are not aware of H. sapiens burials within caves. All of their burials are in cave entrances or in rock shelters. Neanderthals, on the other hand, bury their dead inside the caves (except for EQ3, which was buried in an open-air site).”

Additionally, Homo sapiens burials were very uniform, usually laid out in a flexed (fetal-like) posture. This contrasts with the Neanderthal burials, which were more varied and included individuals buried in flexed, extended (straight), and semi-flexed positions while lying on their left, back, or right.

Furthermore, Neanderthals were more likely to include rocks in their burials, including placing a body between two large rocks as a form of positional marker or placing modified limestone pieces underneath the dead’s heads as a sort of headrest.

Similarly, some aspects of burial were practiced by Homo sapiens but not by Neanderthals, such as having burials associated with ocher and marine shells, which were completely absent in Neanderthal contexts.

Interestingly, the researchers also noted a burial outburst during this time. Not only did burials suddenly appear, but they occurred at a very high rate in an equally condensed region, especially compared to later burials during the MP in Africa and Europe, of which there are only three in all of Africa and 27, albeit very spatially and temporarily separated for Neanderthals in all of Europe.

An increase in population density may partly explain this sudden boom in burials. Due to the increased humidity and, thus, a greater number of flora and fauna in the Saharo-Arabian desert around this time, Homo sapiens were attracted to the region from East Africa.

At the same time, melting glaciers in the Taurus and Balkan mountains opened up pathways to the south, enabling Neanderthals to enter the Levant. There, the two populations met, likely increasing population densities in the area and thus increasing demographic pressure and the presence of burials.

This trend of increased burials continued in the region until they suddenly stopped around 50,000 years ago; according to Prof. Been, “The most striking thing is that in later periods, humans in the Levant did not continue the practice of burials. After the Neanderthals went extinct around 50,000 years ago, cave burials ceased until the Late Paleolithic, around 15,000 years ago, during the Natufian culture, a semi-sedentary hunter-gatherer society.”

The study by Professor Been and Dr. Barzilai not only sheds light on the burial practices of Homo sapiens and Neanderthals in the Levant during the MP but also raises intriguing questions about the cultural evolution of these two species.

“Burials are a significant part of culture, and we know that both Neanderthals and Homo sapiens had some form of culture. It’s puzzling why both populations suddenly started burying their dead, rather than it being due to demographic pressure.”

To better understand the differences and nuances in both Homo sapiens and Neanderthal culture and burials, Prof. Been will continue her research, at present, by styling a Neanderthal burial. She says, “I am currently studying Amud 7—a baby Neanderthal from Amud cave in Israel.”

References

- Ella Been & Omry Barzilai (2024) Neandertal burial practices in Western Asia: How different are they from those of the early Homo sapiens? L’Anthropologie doi: 10.1016/j.anthro.2024.103281 ↩