Free water policy in South Africa

Free water policy in South Africa

Standard supply and demand analysis shows that competitive markets will deliver a given commodity up to the point where costs (as perceived by producers) equal benefits (as perceiver by consumers). When both producers and consumers internalize all costs and benefits, the result is efficient in the sense that the market does not dilapidate resources. An additional feature of competitive markets is that all buyers pay the same price for the good or service in question. This is a characteristic of the market, but is not necessary for efficiency. As long as the price I pay for the last unit I buy reflects the real cost of the good, I will not cause any inefficiency, as the number of units I buy would be the same. Of course, if I pay the first units at a lower price, I will be better off, while the seller will be worse. But this is a matter of distribution, not of efficiency.

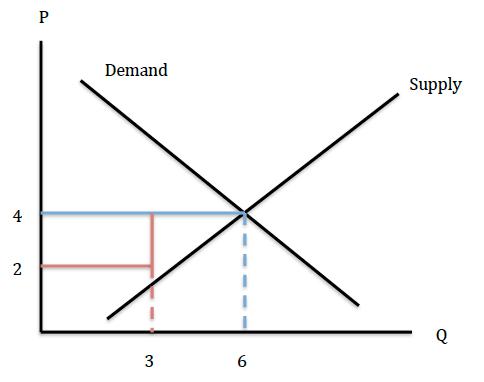

This can be seen in Figure 1. Supply and demand intersect at quantity 6 and price €4. In a standard market (blue lines) consumers will pay €4 for all 6 units (a total of 24). However, under a different payment schedule, consumers may pay €2 for the first 3 units (red lines) and, then, €4 for the next 3 units, adding a total of €18. Under both mechanisms consumers want to buy 6 units: beyond 6 units supply is above demand, meaning that suppliers only accept a price higher than what the demanders are willing to pay. Both mechanisms are equally efficient, but the second is more beneficial for the consumers.

Typically, economic analysis will suggest that monetary redistributions are better than redistributions in kind. The reason is simple: if for some reason you want to give a person or a family €100 worth of good X, you can as well give them €100 in cash. The individual can still buy the good X in the amount you wanted her to have, but she can use the money for something else, indicating that that something else is more valuable to her. For the same price, you will be helping more.

The opening argument of this article is, however, the basis for a special kind of redistributions. Sometimes the government decides that a given good is a merit good, i.e., a good everyone has to consume regardless of their economic situation. Education and health come to mind. Whether a good must be considered a merit good is a political issue. Economic analysis serves to analyze the consequences of using a specific mechanism in the allocation of merit goods. In the case of guaranteeing the access to water, one question is, as stated before, whether free water is better than a money transfer that can be used to buy water. There may be reasons why free water is better: the consumer does not know the need for clean water (for instance, the father in the family is not aware of the work needed to collect clean water made by the mother and would spend the cash transfer in some other goods), the government does not have a census of the individuals in need of water or there is no functioning market for water that can respond efficiently to the increased demand. Another important question is about whether the mechanism performs as desired.

Andrea Szabó does precisely this. In her work, Szabó (2015) 1, she analyzes South Africa’s Free Basic Water Policy, under which households receive a free water allowance equal to the World Health Organization’s recommended minimum. In terms of our example in Figure 1, it would mean that, for all consumers, the first units (the recommended minimum) are free of charge, but the rest has to be paid at market price.

After the apartheid, water was such a sensitive issue that the right to a minimum allowance of free water was written in the constitution after the 1994 elections. As a result, the Free Basic Water Policy was introduced in 2001 and provides 6 kiloliters of water per month at no cost to households, regardless of income or household size.

Szabó collects data of seven years of monthly reading data for every household in a particularly disadvantage suburb in Tshwane (99% Black, with an average monthly household equivalent to 500 US dollars), the metropolitan area around Pretoria. In this suburb about 11% of the 60,000 households have running water but no sanitation, and 30% consume not more than the recommended minimum of 6 kiloliters per month. The data set contains rich price variation across 20 different tariff schedules, a fact that allows the identification of demand parameters and a counterfactual analysis without free water. The 20 tariff schedules include a 2007 policy experiment in which, in an effort to reduce costs, Tshwane’s Water Department introduced a new pricing policy that removed the free water allowance for most households while providing further discounts to the poorest. The data on water consumption are complemented with a survey of 1000 households carried out in December 2010, that collects information on water use and household demographics and income. Finally, the water provider assigns positive accounting prices to free water, as required to receive the subsidy. These prices can be used to formulate the counterfactual scenario in which the free water policy is removed.

Because the complex block pricing structure, regression methods result in biased estimates. Thus, Szabó uses a structural estimation approach. In particular, she takes the extension of the Burtless and Hausman (1978) 2 demand model, which allows her to recover household-level marginal effects and estimate price elasticities (basically, the reaction of households’ demand after changes in the relevant variables), after solving a number of technical econometric problems.

The author offers two main results. First, she analyzes the counterfactual scenario replacing zero price with the positive accounting prices that reflect costs, and finds that household consumption changes very little with the positive price. This result goes in line with the theory depicted in Figure 1: given that the free water consumption is indeed a low quantity, for most households consumption goes beyond that point.

Most importantly, Szabó investigates whether the pricing system of Tshwane can be improved. To make sense of what it means to improve, she assumes that the social planner maximizes consumers’ total expected utility subject to some constraints, like the profitability of the water provider and, in an extension, some revenue and capacity constraints. The difference with a more general version is that here the maximization is restricted to the individuals under study, and not all the population, including the ones that could benefit from higher revenues by the water provided. Szabó finds that, under these restrictions, the optimal tariff contains gradually increasing positive prices with no free allowance. This corresponds to the current government subsidy being spread more evenly across the lower segments. The optimal tariff increases welfare substantially (adding up to an equivalent increase of 3,5% of the median monthly income) while reducing the percentage of consumers with low water consumption. The intuition behind increased consumption is that consumers currently attempt to stay within the free allowance in order to avoid paying the higher current prices.

References

- Szabó, A. 2015. The Value of Free Water: Analyzing South Africa’s Free Basic Water Policy. Econometrica, 83(5), 1913–1961. DOI: 10.3982/ECTA11917 ↩

- Burtless, G., and Hausman, J. A. 1978. The Effect of Taxation on Labor Supply: Evaluating the Gary Negative Income Tax Experiment. Journal of Political Economy, 86(6), 1103–1130. ↩