Sweet, sweet cancers

So many times, I order my coffee while hesitantly eyeing the seductive pastries. This time I’ll resist these sweet beauties.

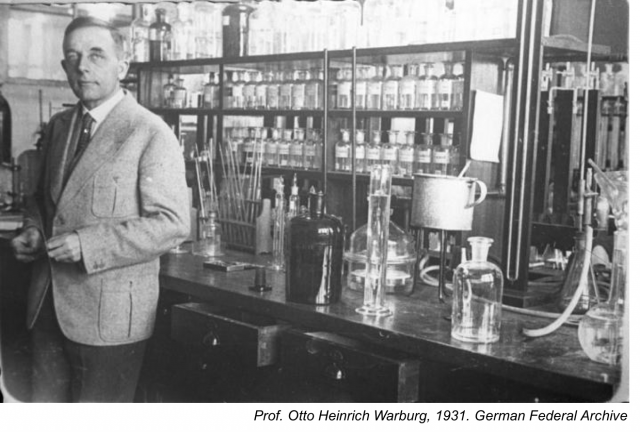

Last night I came across a lecture from Einstein’s friend, Otto Heinrich Warburg (Nobel Prize in Medicine, 1931). It was 1966 and he was at the meeting of Nobel Laureates in Lindau, Germany:

“Cancer, above all other diseases, has countless secondary causes. But, even for cancer, there is only one prime cause. Summarized in a few words, the prime cause of cancer is the replacement of the respiration of oxygen in normal body cells by a fermentation of sugar.”1

To put it simply, Warburg believed cancer cells use an alternative way to extract energy from glucose, which is called fermentation.

A half-century after that lecture we still know very little about what’s going on inside cancer cells. Warburg was not entirely correct about fermentation being the only mechanism that cancer cells use to extract energy but he discovered something crucial: glucose powers cancerous cells.

In the late 70s a new diagnostic test for cancer was discovered, called FDG-PET. This test is still widely used in clinics, and allows doctors to detect cancers and metastases simply by looking at tissues that absorb high levels of glucose. Scary huh?

We still don’t know if high levels of glucose uptake actually cause cancer or if cancer cells strive for more glucose intake 2.

What came first? The chicken or the egg? The sugar absorption or the cancer cell?

Dr. Mina Bissell (Berkeley University), demonstrated that a healthy cell can become a cancer cell by simply increasing its glucose uptake. The study shows that when cells absorb a high amount of glucose, a molecular storm can be triggered inside leading to uncontrolled cell growth 3.

High levels of glucose in the bloodstream (hyperglycemia) is a risk factor for cancer in several organs including pancreas, esophagus, liver, colon, rectum, stomach and prostate 456. Cancer cells burn more sugar than normal cells. This phenomenon contributes to disrupting the metabolism of people with cancer in a very complex and obscure way that the doctors call metabolic syndrome. The weight loss (cachexia) observed in cancer patients is most likely a result of this syndrome 7.

So, is it conceivable that glucose by itself can initiate cancer as Dr. Warburg was claiming 50 years ago?

If this theory is true, it could explain why 90% of people with cancer don’t have any inherited genetic mutation. In other words, this idea could explain why many cancer patients don’t have a family history of the disease.

Put cancer on a diet!

Cancers can double their size within a few days. Such fast and aggressive growth can only be sustained with a steady supply of energy, so cancer becomes more and more ‘addicted’ to glucose as it grows.

Calorie restriction in animal models of cancer have been demonstrated to be effective in slowing the progression of the disease 8. So why don’t we put cancer on a strict glucose-free diet? This is something that scientists are actually trying to do although the metabolism of cancer cells is very complex and difficult to target with drugs. Scientists continue to make discoveries on how glucose is used by cancer cells, which provides the basis of knowledge needed to develop drugs that specifically block glucose breakdown.9

Although the research on cancer metabolism continues to progress, discoveries so far haven’t resulted in an effective therapy against cancer, although they have led to improvements in the detection of cancers.

Would this have disappointed Dr. Warburg? Who knows. He was certainly upset about the “continual discovery of cancer agents…” which apparently could “hinder necessary preventive measures and thereby become responsible for cancer cases” 10.

So here I am at my favorite café, unconcerned about Warburg’s “preventive measures”, with my disarming need to choose between the banana split and a double fudge cake. A man in a bowler hat is sitting next to me. He reminds me of post-war Germany. The same Germany where Dr. Warburg was compulsively looking for fresh and low-sugar food, unaware of the organic diet trend of our times 11.

Dr. Warburg was a hard worker. He pursued his research until the age of 87. He loved riding horses, he never dated and never showed any particular interest in social life. During his late life, he became particularly obsessed with his healthy habits (by most accounts he used to bring his own food to restaurants). He died in 1970.

Note: The author does not promote any “alternative” approach to cancer treatment.

References

- Otto, W., The prime cause and prevention of cancer – Part 1 with two prefaces on prevention. 1966. ↩

- Hsu, P.P. and D.M. Sabatini, Cancer cell metabolism: Warburg and beyond. Cell, 2008. 134(5): p. 703-7. ↩

- Onodera, Y., J.M. Nam, and M.J. Bissell, Increased sugar uptake promotes oncogenesis via EPAC/RAP1 and O-GlcNAc pathways. J Clin Invest, 2014. 124(1): p. 367-84. ↩

- Stattin, P., et al., Prospective study of hyperglycemia and cancer risk. Diabetes Care, 2007. 30(3): p. 561-7. ↩

- Jee, S.H., et al., Fasting serum glucose level and cancer risk in Korean men and women. Jama, 2005. 293(2): p. 194-202. ↩

- Ikeda, F., et al., Hyperglycemia increases risk of gastric cancer posed by Helicobacter pylori infection: a population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology, 2009. 136(4): p. 1234-41. ↩

- Klement, R.J. and U. Kammerer, Is there a role for carbohydrate restriction in the treatment and prevention of cancer? Nutr Metab (Lond), 2011. 8: p. 75. ↩

- Lv, M., et al., Roles of caloric restriction, ketogenic diet and intermittent fasting during initiation, progression and metastasis of cancer in animal models: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One, 2014. 9(12): p. e115147. ↩

- Birsoy, K., et al., MCT1-mediated transport of a toxic molecule is an effective strategy for targeting glycolytic tumors. Nat Genet, 2013. 45(1): p. 104-8. ↩

- Warburg, O., On the origin of cancer cells. Science, 1956. 123(3191): p. 309-14. ↩

- Brand, R.A., Biographical sketch: Otto Heinrich Warburg, PhD, MD. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2010. 468(11): p. 2831-2. ↩