Toxoplasma induces behavioural changes in intermediate hosts and promotes social rise in wolves

Toxoplasma induces behavioural changes in intermediate hosts and promotes social rise in wolves

Author: Ramón Muñoz-Chápuli has been Professor of Animal Biology in the University of Málaga until his retirement. He has investigated for forty years in the fields of developmental biology and animal evolution.

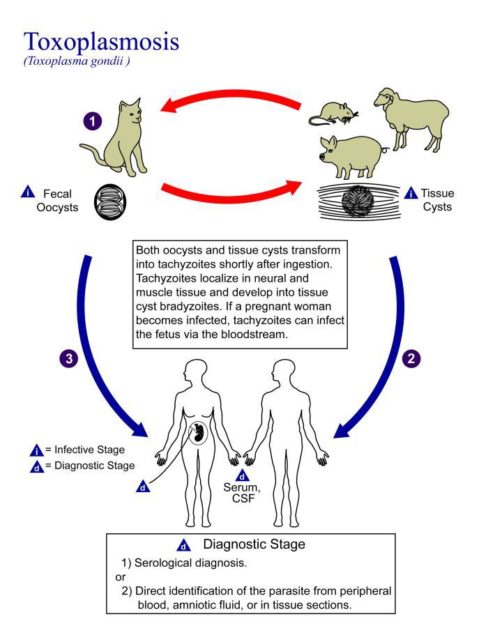

Toxoplasma gondii is a protozoan parasite of warm-blooded animals, including humans. After the acute phase of the infection, the parasite remains latent in cysts located in the muscular or brain tissue, without causing clinical symptoms. In humans, acute infection is not serious, except in the case of foetuses or immunosuppressed people. Its prevalence is very high. It is estimated that at least one third of the world population is a carrier of the parasite in the latent phase.

The Toxoplasma life cycle is very peculiar. Only in felines (cats, lions, leopards), Toxoplasma can reproduce sexually and produce oocysts. Any other warm-blooded vertebrate can be an intermediate host, after becoming infected by eating another intermediate host or by ingesting oocysts dispersed in the environment by scats from the definitive feline host. It has been hypothesized that Toxoplasma provokes changes in the behaviour of intermediate hosts to promote the transmission to a feline. For example, rats infected with Toxoplasma lose their natural aversion to cat urine. In addition, infected rodents show enhanced exploratory behaviour and less avoidance of novelty, increasing the probability of being captured by cats and transmitting the infection to them 1. Something similar was observed in chimpanzees infected with Toxoplasma, which lose their innate aversion towards the urine of leopards 2.

Until now these behavioural changes had been studied in captivity, but two recent investigations have shown that in wildlife Toxoplasma also influences the behaviour and decision-making of the infected intermediate host, and even of its social group. Infected hyenas, for example, are bolder, take more risks and, as a consequence, they are more likely to be eaten by african lions 3. Another study, carried out over 26 years by a team of Yellowstone park biologists, has shown that infected gray wolves show greater territorial overlap with pumas, as well as a greater trend for territorial dispersal and risk-taking behaviour 4. In addition, infected males are much more likely to become the leaders of their pack and influence the decisions of their social group, including the approach to areas inhabited by pumas. Since infected wolves are unlikely to be preyed on by pumas, as is the case with hyenas and lions, the grounds for these behaviours are not evident. The leader of the pack achieves greater reproductive success, but the advantages are likely to be offset by the negative consequences of toxoplasmosis, such as the foetal lethality of the acute infection. In addition, infected wolves are less avoidant of humans and more susceptible to being run over or hunted. It can be speculated that the evolution of bold behaviour in wolves occurred in remote times, when North America was populated by the American lion (Panthera atrox), a large superpredator that became extinct 11,000 years ago. Perhaps the altered behaviour of the infected wolves made them more susceptible to being eaten by lions.

The behavioural changes of infected intermediate hosts can be considered an instance of “extended phenotype”, a term coined by Richard Dawkins. This concept refers to the possibility that the product of gene expression (in this case the Toxoplasma genes) manifests itself beyond the organism, affecting the environment or social behaviour.

What is the physiological explanation for the behavioural changes caused by latent Toxoplasma infection? Many aspects of this issue are unknown, but it has been shown that infected mice produce 14% more dopamine in their brains. Other animals, including humans, show an increase in testosterone, both in males and in females 5 . These hormonal changes can lead to more active, bolder and aggressive behaviour.

As we said above, about a third of human beings are asymptomatic carriers of Toxoplasma. Would this involve behavioural consequences? Studies have been published linking obsessive-compulsive disorder and other affective conditions with the presence of antibodies against Toxoplasma in the blood 6.

In summary, the recent studies on Toxoplasma highlight the importance of the coevolutionary processes between hosts and parasites, which can generate not only physiological consequences for the host, but also ecological and ethological impacts that go beyond infected individuals.

More on the subject:

References

- Barford, E. (2013) Parasite makes mice lose fear of cats permanently. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature.2013.13777 ↩

- Poirotte C, Kappeler PM, Ngoubangoye B, Bourgeois S, Moussodji M, Charpentier MJ. (2016) Morbid attraction to leopard urine in Toxoplasma-infected chimpanzees. Curr Biol. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.12.020. ↩

- Gering E, Laubach ZM, Weber PSD, Soboll Hussey G, Lehmann KDS, Montgomery TM, Turner JW, Perng W, Pioon MO, Holekamp KE, Getty T. (2021) Toxoplasma gondii infections are associated with costly boldness toward felids in a wild host. Nat Commun. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24092-x. P ↩

- Meyer CJ, Cassidy KA, Stahler EE, Brandell EE, Anton CB, Stahler DR, Smith DW. (2022) Parasitic infection increases risk-taking in a social, intermediate host carnivore. Commun Biol. doi: 10.1038/s42003-022-04122-0. ↩

- Zouei N, Shojaee S, Mohebali M, Keshavarz H. (2018) The association of latent toxoplasmosis and level of serum testosterone in humans. BMC Res Notes. doi: 10.1186/s13104-018-3468-5. ↩

- McConkey GA, Martin HL, Bristow GC, Webster JP. (2013) Toxoplasma gondii infection and behaviour – location, location, location? J Exp Biol. doi: 10.1242/jeb.074153. ↩