Extracting the stone of madness: the art of brain surgery in the Renaissance

Extracting the stone of madness: the art of brain surgery in the Renaissance

madness

Authors: Chiara Bressan, student of the European Master’s in Clinical Linguistics & Adrià Rofes, assistant professor of neurolinguistics at the University of Groningen

Imagine yourself tied to a chair. You cannot move, you are fully conscious, and a strange individual behind you is about to carve into your skull. No, you are not an extra in the Hannibal Lecter movie, and no, you are not having a nightmare. You are living in the 1500s and are considered insane. You are, in a nutshell, a lunatic.

Lunatic, moonstruck, foolish, were, in ancient times, terms used to refer to someone who was mentally ill. It was thought, in fact, that the moon had some influence on people’s psychological status. These beliefs were particularly in vogue between the 15th and the 16th century, when the cause of psychiatric patients’ problems was thought to be a stone embedded in their brains: the stone of madness. To heal these patients, the stone had to be extracted by opening the brain, with a procedure called cranial lithotomy 1 .

Now, imagine for a second that you actually have a stone in your head. How would you feel? You would probably suffer from severe headaches, changes in behavior, speech problems, and even epileptic seizures from time to time, depending on where exactly the stone is located in your brain. In order to remove it, you would need surgery, sometimes even “awake surgery”, a practice in which the patient is awake while the doctor is extracting the stone. But wait: was this really a thing during the Renaissance? Let’s have a quick look at the arts of the time.

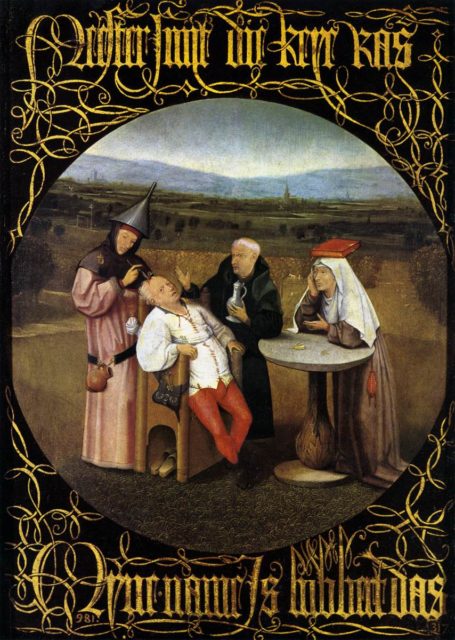

The earliest representations of skull incisions in European paintings date back to the 12th century 2. A series of paintings of the 15th and 16th century, mainly from Dutch art, show people performing craniotomies on wide-awake patients. Their eyes look dull and terrified – who wouldn’t be? – and they are often surrounded by priests and merciful ladies. The most famous example is Hieronymus Bosch’s The cure of folly (1494), but many other artists of the same period depicted this kind of brain operations.

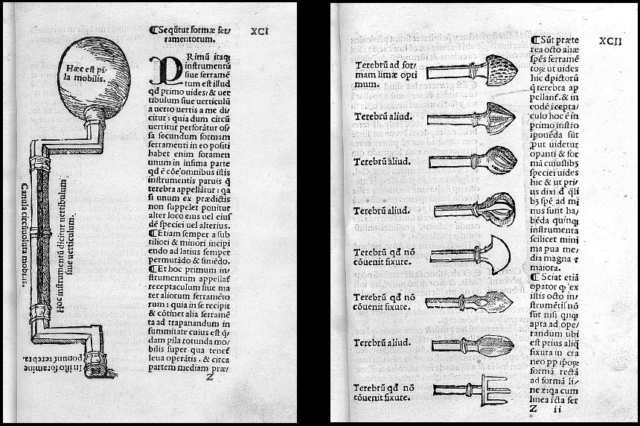

Surgeons at that time, probably much to their disappointment, did not find any stones in those patients’ heads, although some very rare cases of ‘cerebral calculi’ (Ladino et al., 2013), a form of calcifications leading to tumors, have been reported in the literature. The representation of the extraction of the stone of madness had more of a symbolic value, wishing to ironically portray the meaningless barbarity of such a practice, usually performed by quacks, and to condemn the treatment reserved for the foolish (Krischel et al., 2014). Although it is very unlikely that this method would actually be implemented to extract a stone, some medical texts of the time recommended opening the skull through trepanation as a remedy to treat diseases like epilepsy, brain injuries, or in some cases mental illness. The idea behind the trepanation was to let the brain breathe and the bad humors to evaporate 3. The procedure is described in Berengario da Carpi’s Treatise on skull fractures (1518), and a detailed illustration of the specific tools is provided 4).

Rudimentary drills with different shapes were used. Types and locations of incisions changed according to the nature of the injury. Berengario indicates the temporal bone as the ideal site to perform a craniotomy and expresses the necessity to open the cranium to evacuate pus and apply dressing to the dura mater.

Before surgery, patients also had to confess their sins to God since, according to common opinion, these were often the cause of illness. Brain diseases were in fact believed to be divine punishment. The lesion would be treated in most cases with herbal ointments and potions such as clover, rose oil, strawberry leaves, and cannabis, while surgery was recommended only in extreme necessity, but still performed (Lind & Da Carpi, 1990). Archaeological excavations confirm that most trepanations were performed on the left side of the skull and the most used techniques were scraping, cutting and drilling, with a quite good survival rate, according to signs of healing found in the bones 5. Primitive and curious neuroanesthetics, such as a mixture of newly whelped puppies boiled in oil of lilies and earthworms 6 – yes, you read it right – would sometimes also be topically or orally administered.

In summary: it is pretty clear that brain surgery in the Renaissance was still deeply tied to mystical superstitions, but these offer an interesting overview of the progress medicine made through the centuries. Those paintings, though intended to ridicule the practice, give us the first snapshots of awake craniotomies in Europe. Today we look at these bizarre procedures with a smile, but what was called the stone of madness more than five hundred years ago, today would be nothing less than a tumor, also known to be one cause of behavioral changes, or in other terms, madness. Whether you call it tumor, stone, or mental illness, it is always about something depriving you of yourself by altering your mind. If we bring all of this to the 1970s, one of the best definitions was given by Pink Floyd, when they sang in Brain damage: ‘There’s someone in my head but it’s not me’. After all, what is madness, but the loss of self?

References

- Krischel, M., Moll, F., & Van Kerrebroeck, P. (2014). A stone never cut for: A new interpretation of the cure of folly by Jheronimus Bosch. Urologia internationalis, 93, 389-393. DOI: 10.1159/000362741 ↩

- Ladino,L.D., Hunter, G., & Téllez-Zenteno, J.F. (2013). Art and epilepsy surgery. Epilepsy and Behavior, 29, 82-89. DOI: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.06.028 ↩

- Gross, C. (2012). A hole in the head: More tales in the history of neuroscience. The MIT Press. ↩

- Lind, L.R., & Da Carpi, B. (1990). Berengario da Carpi on fracture of the skull or cranium. Transactions of the American philosophical society, 20(8), 1-164. ↩

- Giuffra, V., & Fornaciari, G. (2017). Trepanation in Italy: A review. International journal of osteoarchaeology, 27(5), 745-767. https://doi.org/10.1002/oa.2591 ↩

- Chivukula, S., Grandhi, R., & Friedlander, R. M. (2014). A brief history of early neuroanesthesia. Neurosurgical focus, 36(4), E2, 1-5. DOI: 10.3171/2014.2.FOCUS13578 ↩

1 comment

[…] the stone of madness: The art of brain surgery in the Renaissance, Mapping Ignorance. Available at: https://mappingignorance.org/2023/03/01/extracting-the-stone-of-madness-the-art-of-brain-surgery-in-… (Accessed: 19 January […]