How to make carbonaceous cosmic dust in the lab

How to make carbonaceous cosmic dust in the lab

A Univerity of Sydney Ph.D. student has recreated a tiny piece of the universe inside a bottle in her laboratory, producing cosmic dust from scratch. The results shed new light on how the chemical building blocks of life may have formed long before Earth existed.

Linda Losurdo, a Ph.D. candidate in materials and plasma physics in the School of Physics, used 1 a simple mix of gases—nitrogen, carbon dioxide and acetylene—to mimic the harsh and dynamic environments around stars and supernova remnants. By subjecting these gases to intense electrical energy, she generated carbon-rich “cosmic dust” similar to the material found drifting between stars and embedded in comets, asteroids and meteorites.

Carbonaceous cosmic dust

The dust she created contains a complex cocktail of carbon, hydrogen, oxygen and nitrogen—known collectively as CHON molecules—which are central to many organic substances essential for life.

“We no longer have to wait for an asteroid or comet to come to Earth to understand their histories,” Losurdo said. “You can build analog environments in the laboratory and reverse engineer their structure using infrared fingerprints.

“This can give us huge insight into how ‘carbonaceous cosmic dust’ can form in the plasma puffed out by giant, old stars or in cosmic nurseries where stars are being born and distribute these fascinating molecules that could be vital for life. It’s like we have recreated a little bit of the universe in a bottle in our lab.”

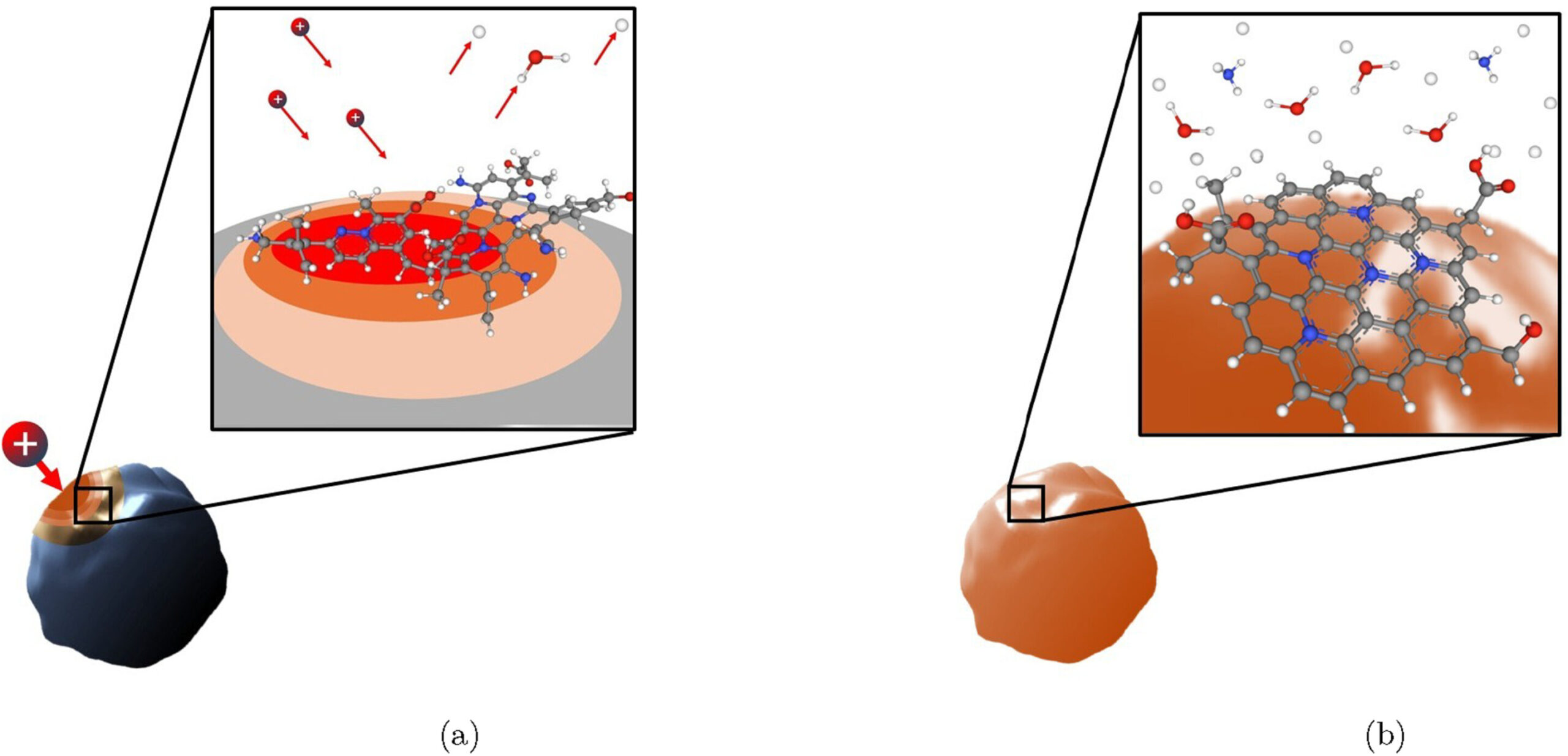

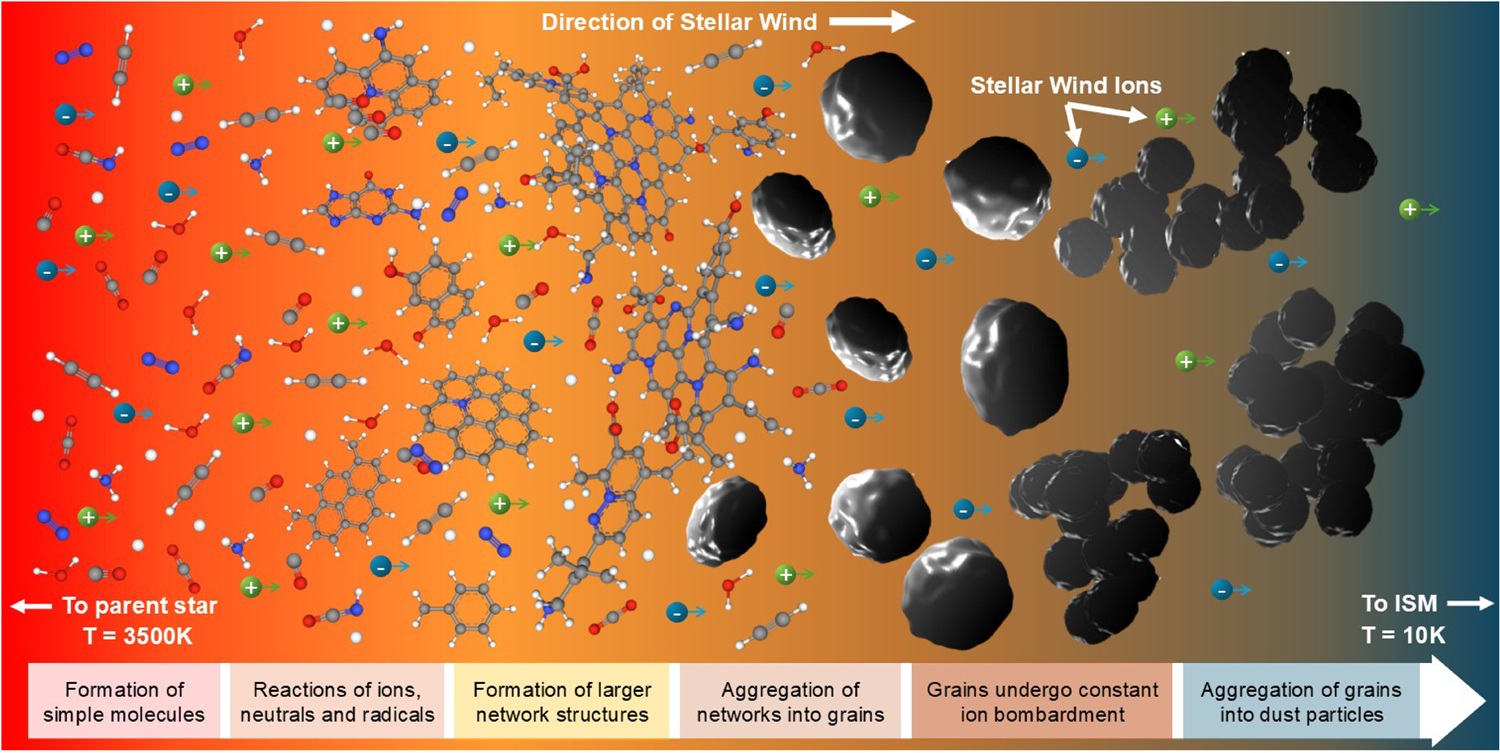

Cosmic dust is known to form in extreme astrophysical environments, where molecules are constantly bombarded by ions and electrons. Scientists can identify this dust in space because it emits a distinctive infrared signal—a molecular fingerprint that reveals its chemical structure.

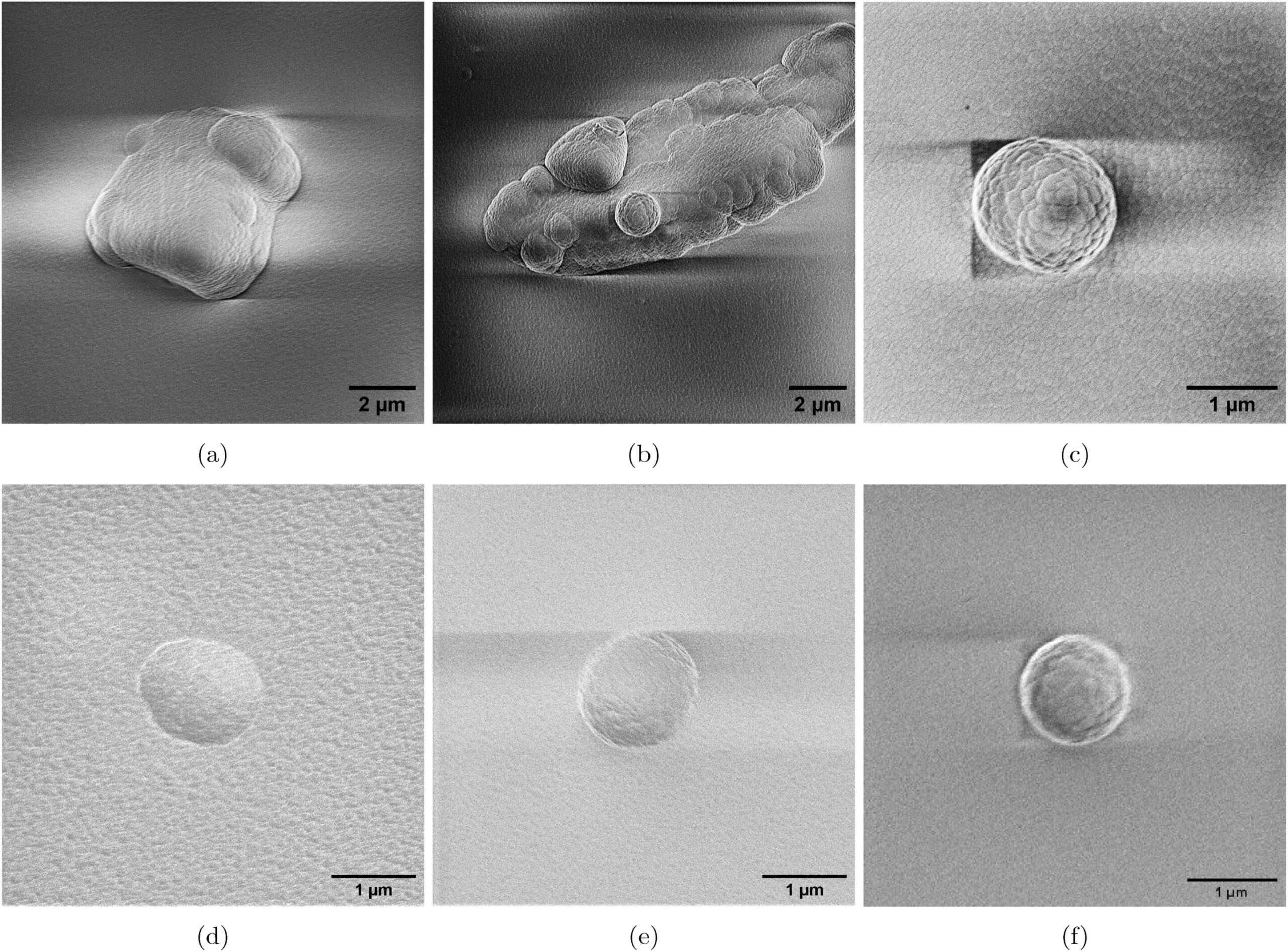

The dust produced in Losurdo’s experiments showed the same tell-tale infrared signatures, confirming the laboratory process closely mirrors what happens in space.

Building blocks of life

One of the enduring questions in science is how life began on Earth. Researchers are still debating whether the earliest organic molecules formed locally on our young planet, arrived later aboard comets and meteorites, or were delivered during the earliest stages of solar system formation—or some combination of all three.

Between about 3.5 and 4.56 billion years ago, Earth was bombarded by meteorites, micrometeorites and interplanetary dust particles originating from asteroids and comets. These objects are thought to have delivered vast amounts of organic material to the planet’s surface. Yet the origins of that material remain mysterious.

“Covalently bonded carbon and hydrogen in comet and asteroid material are believed to have formed in the outer envelopes of stars, in high-energy events like supernovae, and in interstellar environments,” Losurdo said.

“What we’re trying to understand are the specific chemical pathways and conditions that incorporate all of the CHON elements into the complex organic structures we see in cosmic dust and meteorites.”

Cosmic dust from scratch

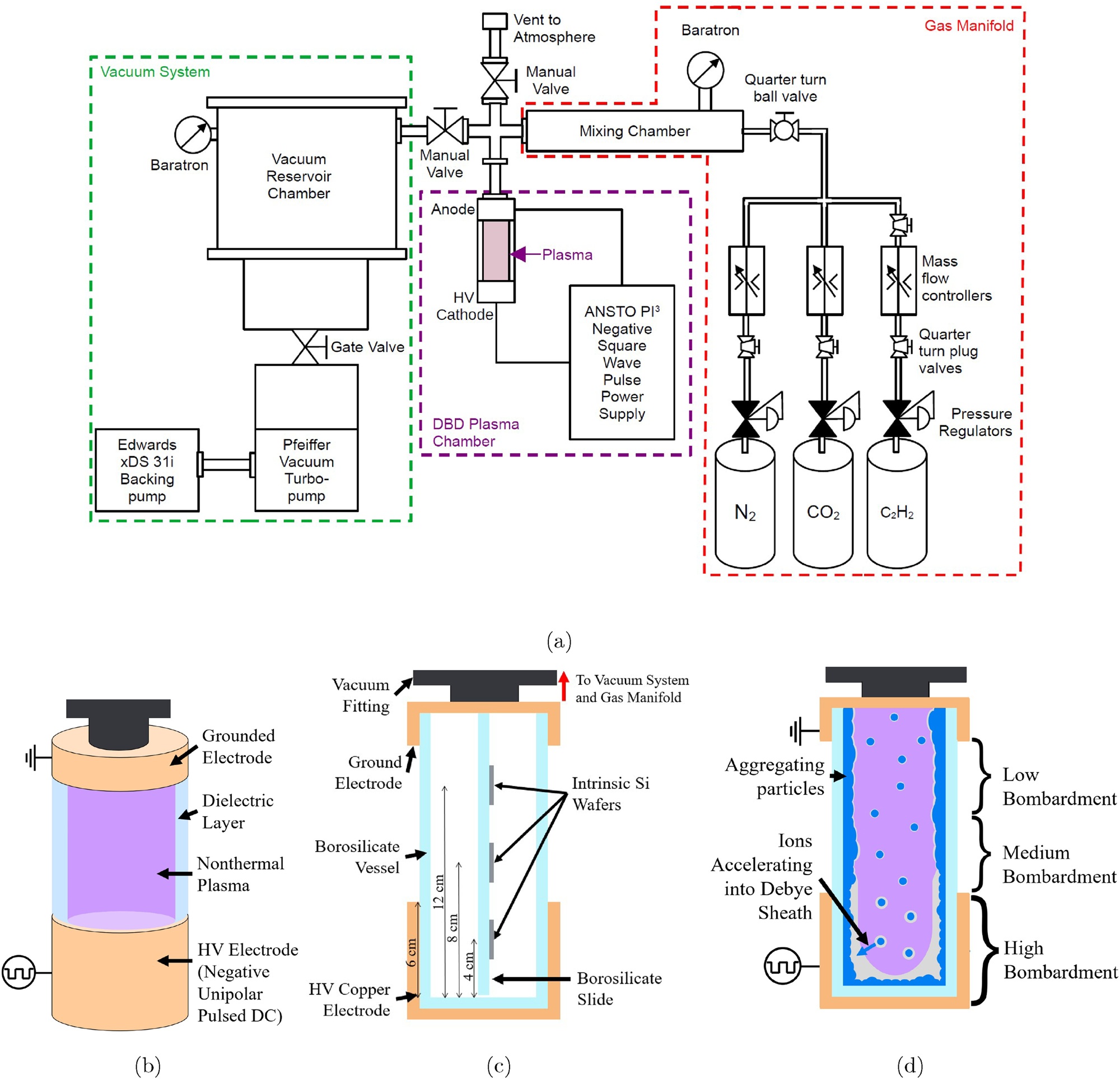

In the experiment, the team, consisting of Losurdo and her supervisor, Professor David McKenzie, used a vacuum pump to evacuate air from glass tubes, recreating the near-empty conditions of space. Nitrogen, carbon dioxide and acetylene were then introduced. The gas mixture was exposed to about 10,000 volts of electrical potential for about an hour, creating a type of plasma known as a glow discharge.

Under this intense energy, molecules broke apart and recombined into new, more complex structures. These compounds eventually settled as a thin layer of dust on silicon chips placed inside the tubes. The collected dust at times looks like glittering collections of cosmic material.

Professor McKenzie, co-author on the paper, said the work will allow scientists to probe conditions that are otherwise impossible to study directly.

“By making cosmic dust in the lab, we can explore the intensity of ion impacts and temperatures involved when dust forms in space,” Professor McKenzie said. “That’s important if you want to understand the environments inside cosmic dust clouds, where life-relevant chemistry is thought to be happening.

“This also helps us interpret what a meteorite or asteroid fragment has been through over its lifetime. Its chemical signature holds a record of its journey, and experiments like this help us learn how to read that record.”

Beyond insights into the origins of life, the researchers aim to build a comprehensive database of infrared fingerprints from lab-made cosmic dust. Astronomers could then use this library to identify promising regions of space—in stellar nurseries or the remnants of dead stars—and work backwards to understand the processes shaping them.

By recreating cosmic chemistry on Earth, the research opens a new window onto deep stellar processes—and the ancient steps that may have helped make life on Earth possible.

.

References

- Linda R. Losurdo and David R. McKenzie (2026) Carbonaceous Cosmic Dust Analogs Distinguish between Ion Bombardment and Temperature ApJ doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/ae2bfe ↩