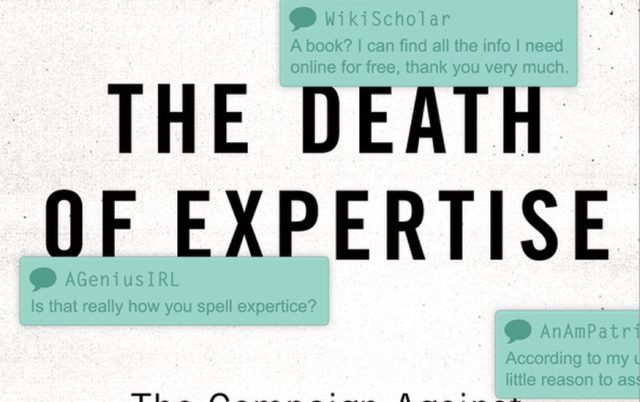

The Death of Expertise

During the last decades and, especially, throughout the 21st century, expertise is in decline in the USA. This is the subject that the author addresses in his book. I have been interested in it since I learned of its existence because I have the impression that something similar is happening in Spain, although perhaps to an even lesser extent.

We live in dangerous times, according to Tom Nichols. Never have so many people had access to so much knowledge and yet are so reluctant to learn. Otherwise intelligent people denigrate intellectual achievements and reject the advice of experts. Not only do laymen increasingly lack basic knowledge, but they also reject the fundamental rules of evidence and refuse to learn how to construct a logical argument. They thus risk dispensing with the knowledge accumulated over centuries and undermining the practices and habits that allow us to develop new knowledge.

The problem is not only that ignorance is gaining ground over knowledge, but the vacuous, unfounded arrogance that leads to the indignation of a narcissistic culture that cannot stand the slightest hint of inequality of any kind. For one of the foundations of this phenomenon is precisely the claim that we are all equal in all respects, including those relating to the acquisition of knowledge.

Expertise or authority?

The death of expert knowledge does not consist only in the rejection of existing knowledge. It is, above all, a rejection of science and dispassionate rationality, which are the foundations of contemporary civilization. People are skeptical of authority and, at the same time, prey to superstition. They believe that enjoying equal rights in a political system implies that anyone’s opinion on any subject should be accepted as equal to any other.

This should not be considered a novelty. Attacks on established knowledge have a very long pedigree; the internet is only the most modern tool in a recurring trend that, in the past, resorted to television, radio or the printing press.

Biases and customers

At the root of this problem is the tendency not to accept those things that contradict thoughts and beliefs we have firmly entrenched. We all fall prey to biases, such as confirmation bias. We all have personal experiences, prejudices, fears and phobias that prevent us from accepting the advice of those who know. We all have them, but in a good number of people, at superlative levels.

On the other hand, access to university education has greatly expanded, although the quality of the education provided has declined significantly, at least in the opinion of Nichols and many others. The reason is that, even in good universities, the student is treated as a customer and the customer is always right. The customer, when treated as such instead of as a learner, acquires great self-esteem, but little valuable knowledge. Worse, he does not develop the critical thinking that would enable him to continue to learn and evaluate the kind of complex subjects he will have to deliberate and vote on as citizens.

So far this century, the internet has facilitated and reinforced human failures. It is a phenomenal tool for spreading knowledge, but also for spreading disinformation. We can speak of an infodemic or pandemic of disinformation. People, instead of debating, fight, and instead of listening, insult.

On the other hand, journalists should be the referees in the great melee between ignorance and learning. But the public wants to be entertained, not informed. And, in any case, they want to be proved right, to have their beliefs and thoughts confirmed. The flow of information to which we have access is enormous because the channels are so numerous and information must be provided continuously. In this scheme, messages are simplified. Priority is given to the headline or the quote, with no more context to analyze in many cases.

As if the above were not enough, experts also make mistakes, and in some cases the errors have had catastrophic consequences. In others, they have acted in the service of vested interests, whether ideological, political or economic, in violation of the most basic principles of professional ethics. The mistakes have consisted of well-intentioned errors, in some cases, and overconfidence driven by arrogance in others. Lay people should know that experts are sometimes wrong, but, at the same time, they must accept that even if they are wrong, they know more than non-specialists in their subjects.

It is also important for people to be aware that experts are not (and should not be) the ones who make policy decisions on the issues they know about. They are the politicians, but they must be advised by experts and the public must know that this is so. Experts advise; politicians decide.

Experts have a responsibility to educate people; citizens have a responsibility to learn. A stable democracy in any culture relies on the public to understand the implications of their own choices; for that reason, anti-intellectualism is itself a form of short-circuiting democracy.

Part of the social contract

In a democracy, expert service to the public is part of the social contract. Citizens delegate decision-making power on a myriad of issues to elected representatives and their expert advisors, while the latter, for their part, demand that their efforts be understood in good faith by a public that has been informed to a sufficient extent to make reasoned judgments about the matters on which to deliberate and decide.

When trust breaks down, experts and laymen become combatants, enemies. Functional citizenship collapses and triggers a cascade of other catastrophic consequences. And when that happens, democracy enters a spiral that risks precipitating either into mass law or into an elitist technocracy. Both are authoritarian outcomes. And both constitute a real threat.

The creation of a vibrant intellectual and scientific culture in the West required democracy and tolerance. Without those virtues, knowledge and progress fall prey to religious, ideological and populist attacks.

The Death of Expertise has stirred up mixed feelings in me. In general terms, I share the author’s thesis, but, on the other hand, I believe that this book lacks a more critical analysis of the attitude and pretensions of many experts. I am referring to the fact that on too many occasions they present as valid knowledge what are no more than opinions, better or worse founded, but opinions nonetheless.

Many experts also seem to be unaware that what they present as expert knowledge is heavily conditioned by biases whose existence they seem to ignore. Many experts should, in general, be more prudent than they are, and certainly humbler. Expert knowledge is indeed irreplaceable in a democratic society, but everyone, including them, must be aware of its limitations and act accordingly.

The book:

Title: The Death of Expertise. The Campaign against Established Knowledge and Why It Matters

Author: Tom Nichols

Ed. by Oxford University Press, 2017

A previous version of this article was published in Book reviews & random thoughts