Ever since Wallace

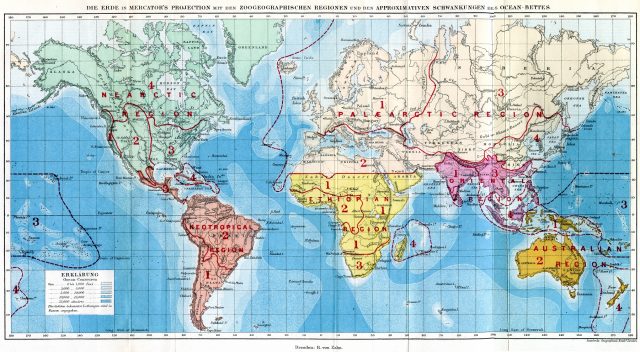

Alfred Russel Wallace (1823-1813) is especially known as one of the discoverers of evolution by natural selection. However, among his various contributions to the development of modern biology we can also consider the British naturalist as the father of biogeography: the study of the spatial distribution of organisms over the surface of the planet. Wallace’s travels, first through the Amazon rainforest and later all over the Malay Archipelago, gave him a privileged perspective on an apparently trivial observation: different areas host different animals. He was the first person to systematically define and name a geographic area by the integrity of its fauna (mainly based on mammals), in other words, to enclose a region within a virtual border that reflects a more or less dramatic turnover in the composition of animal species, genera or families between both sides of this border. After a remarkable synthetic work, he summarized his conclusions in a map that still looks familiar to modern biologists.

In this map, Wallace recognized six highest-rank zoological regions (sometimes called “realms” or “kingdoms”) hosting a distinct zoological assemblage: Palearctic (including Europe, most of Asia and Africa north of Tropic of Cancer), Nearctic (Most of North America), Ethiopian (Sub-Saharan Africa and Madagascar), Neotropical (Central and South America), Oriental (Southeastern Asia and part of the Malay Archipelago) and Australian (the remaining Malay Archipelago, Australia and other Indo-Pacific islands). It is important not to confuse biogeographic regions with ecoregions (defined by the environmental and ecological conditions, and not by taxonomic integrity). Also, it is adequate to remember the existence of floristic regions, defined by the integrity and singularity of plant taxa, whose borders often (but not always) resemble those of the zoological regions.

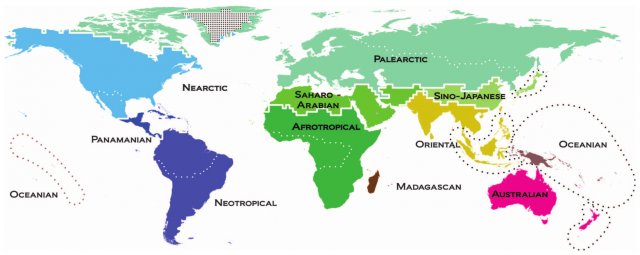

Of course, the map did not remain completely unchanged, and biogeographers have often reconsidered these borders or split some of those regions. However, it is interesting that this year, precisely during the centennial of the death of the father of the biogeography, a novel approach to a global zoologeographic map has been published honoring Wallace 1. This proposed update includes a novel methodological highlight: for the first time the integrity of the zoological regions has been studied using the distribution of more than 21,000 species of vertebrates (amphibians, nonpelagic birds and nonmarine mammals) and their phylogenetic relationships. Therefore, not only the current distribution of the taxa is considered, but also the historic dimension tracked by molecular phylogenetics, providing a significant improvement of the data quality.

The 2013 map recognizes the existence of 11 broad-scale zoological regions, and while it validates much of Wallace’s conclusions, also includes as distinct “realms” the Panamanian, the Saharo-Arabian and the Sino-Japanese regions. Additionally, Madagascar is split from the Afrotropical (Ethiopian) Region, as well as New Guinea and other Pacific islands are, according to the data, distinct enough from the Oriental and Australian regions. Another major difference is that the Palearctic Region reaches the northernmost parts of North America.

Obviously, these different zoogeographic areas are the result of a complex interaction between the evolving land vertebrates and the physical environment they inhabit, which is also slowly but constantly changing its characteristics and relative position due to geologic processes. The historical component is vital to understand modern biogeographic patterns, such as the striking differences between the two hemispheres.

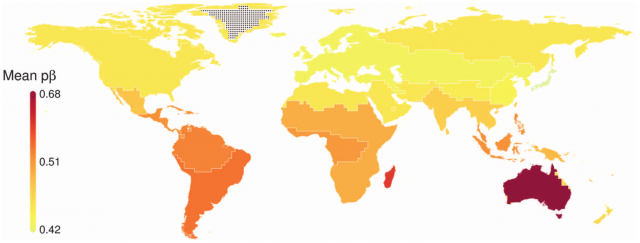

In the map above, areas are colored according to the “uniqueness” of the taxa they host: the darker the color, the more distinct and original its fauna. While vast areas of the Palearctic and Nearctic do not seem to have a very singular vertebrate assemblage, the southern hemisphere, in spite of its reduced land surface, shows an extraordinary rich and unique taxonomic combinations, and not only restricted to Australia or Madagascar, but also throughout South America, Africa and the Malay Archipelago: all these land masses spent a long time of their past isolated (even if they merged to other continental areas recently), while Eurasia and North America shared a linked and relatively homogeneous geologic history.

Ultimately, we may wonder whether these results represent a good delimitation of biogeographic areas beyond mammals, birds and amphibians. It may be too soon to answer this question. Even within the three groups included in the study, the borders may show some differences if we choose a single vertebrate lineage instead of the combined approach. However, the use of large datasets of both, current distributions and phylogenetic information, is very promising for future research that may expand this new type of “cartographic effort” to groups of invertebrates and plants. Wallace would be delighted.

Google Earth and GIS map layers of this updated delimitation of the zoogeographic regions are available at the website of the Center for Macroecology, Evolution and Climate of the University of Copenhagen.

References

- Holt, B. G., Lessard, J-P., Borregaard, M. K., Fritz, S. A., Araújo, M. B., Dimitrov, D., Fabre, P-H., Graham, C. H., Graves, G. R., Jonsson, K. A., Nogués-Bravo, D., Wang, Z, Whittaker, R. J., Fjeldsa, J. & Rahbek, C. 2013. An Update of Wallace’s Zoogeographic Regions of the World. Science339, 74–78 ↩

7 comments

Very nice article! I am not into these topics at all, so I have a generic question. Birds might be the animals with highest mobility, but the variability of differentiated bio-geographic areas is much higher. My common sense is telling me that they should be more uniform due to their higher mobility… what am I missing?

Actually I think that the number of areas is the same or almost the same for both lineages (they forced it, I would say), they just have a different pattern, and colors are chosen in order to reflect their affinity. It may be surprising how uniform and large are Northern amphibian regions, but on the other hand, bird areas in Africa are much larger, as expected.

What you said about bird dispersal is right, of course, but still many birds are not present everywhere they could physically reach. and even if some birds species span over huge areas, that would not prevent the existence of a biogeographic border within them if other assemblages of bird fauna are distinct because of other circumstances (Regional bloom of lineages, full niches in the adjacent area…). Also, sometimes we think that flight overcomes any geographic barrier, but mountains or oceans are indeed obstacles for many birds (I was surprised when I learnt that the Strait of Gibraltar, only 15 km of sea, is still a critical point on bird migration, and many of them die trying to cross it).

That was indeed one of Wallace’s discoveries on the Malay Archipelago: some bird assemblages seemed “unable” to cross a particular strait (Bali-Lombok), even though the distance between land masses were not larger than other straits with no effect on bird fauna.

(My two cents)

Thank you for your comment!

You made me count the number of differentiated areas to check… that you are right! 😀 Both amphibians and birds have the same number of areas, it might be the way they are placed that confused me.

Thank you for your extended answer!

Nice article, I will read the orignial paper, you have stirred up my curiosity.

Oh great! And thank you for your comment.

[…] por otras contribuciones entre las que destaca muy merecidamente un rol casi fundador de la biogeografía moderna. Es cierto que un descubrimiento simultáneo, o la publicación del mismo, conlleva cierto […]

[…] Download Image More @ mappingignorance.org […]