Endemic daffodils and natural heritage

Endemic species are part of the natural heritage of a region, and their preservation for future generations should receive the same kind of priority and public understanding as historical sites, because they share a common trait: if they disappear, they will be lost forever. Of course, conservation becomes especially thorny if we are not sure about how many species should be recognized and which of them deserve special protection. Resources available for ecosystems and species preservation are usually scarce, and their allocation must be done according to our best scientific understanding. This is how systematics may acquire also a dimension in public responsibility.

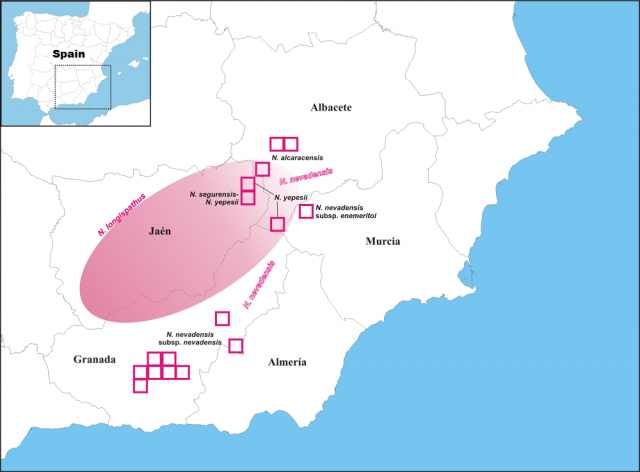

We can find an interesting example in the daffodils of southern Spain, where the recognition of endemic species has been a matter of botanical controversy for a long time. The taxonomy of the daffodils (genus Narcissus) is arguably very complex, even devilish. Within the section Pseudonarcissus (which includes several daffodils very popular in gardening), the number of species recognized in the area has varied between one and seven. The subtle but broad morphological variation among the flowers suggested that some alpine populations in the Baetic ranges represented isolated taxa that deserved taxonomical recognition. In 1933, Narcissus longispathus was described originally from Cazorla mountains and N. nevadensis from Sierra Nevada. About half a century later (1986), the remaining midland populations were acknowledged as a distinct species: Narcissus bujei, different from N. pseudonarcissus. The splitting of local forms continued in recent years with the description of microendemisms from other potentially isolated populations across the eastern Baetic ranges: Narcissus alcaracensis, N. segurensis, N. yepesii and N. enemeritoi.

The validity of these species has been frequently disputed, especially the most recent ones. The degree of confusion that can be reached is remarkable, and it is tempting to conclude that this taxonomic inflation does not reflect “real entities”, but an arbitrary and artificial atomization of variation, perhaps seeking some kind of geographical prominence of local endemisms. Just to give an idea of the extreme difficulty of the taxonomic delimitation of these daffodils, in the recent synthetic approach of Flora Iberica all these local forms were lumped into N. pseudonarcissus, and recognized, at most, as subspecies.

This does not mean that the morphological variation recorded by the taxonomists who described the local endemisms was not accurately reported; what was argued was, instead, the evolutionary meaning of this variation. We all know that species vary (sometimes very much), but are these subtle variations the result of independent evolution, or do they rather constitute the expected plasticity of a widely distributed continuum? The answer is not trivial: there are not magic recipes for species delimitation, and they may exist regardless of any morphological sign (this is the case of cryptic species), what is important from a scientific point of view is being able to recognize populations that represent unique, discrete lineages… even is this is not an easy task.

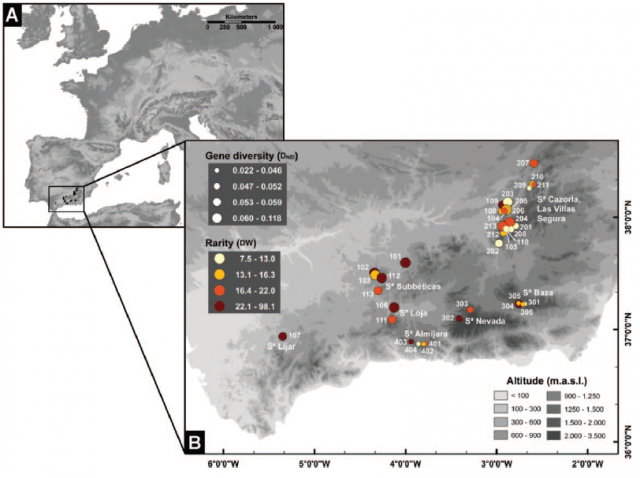

In the case of truly cryptic or almost cryptic species, molecular information becomes an invaluable source of information. A recent study1 [PDF] conducted at Doñana Biological Station used AFLP (Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism, a genetic fingerprinting technique used to estimate phylogenetic distance within closely related populations) to detect discrete genetic clusters within the endemic forms of daffodils of the section Pseudonarcissus in southern Spain. The field work included the sampling of 538 individuals belonging to 36 populations across the Baetic ranges, and the resulting AFLP patterns were analyzed under three different methods.

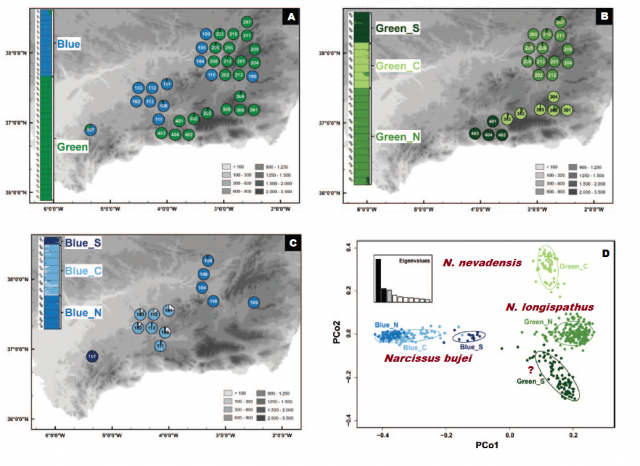

The results consistently showed a big gap between the genetic distance of two groups of populations (named by the researchers the “blue” and the “green” group to avoid any taxonomic preconception). Within both of these groups, other clusters were also recognized statistically and named “N” (north), “C” (Center) and “S” (South), according to the geographic area of the subgroup. Do these genetic groups correspond to the taxonomic entities described morphologically? If so, which of the existing hypotheses fits better the AFLP study?

It turns out that the blue group corresponds precisely to the populations under the name of Narcissus bujei, and its distinction from the rest of the forms of the section is strongly supported. According to the authors, however, the three subgroups within the blue cluster (N, C and S) reflect only divergence through a geographic gradient and probably are not the result of evolutionary divergence. The green cluster, on the other hand, is comprised of three subgroups whose differentiation is not only correlated to geographic distance, but also to some sort of long-term isolation, consequence of speciation processes. Two of the subgroups can be ascribed to previously recognized morphospecies: the Green_N group would fit the idea of N. longispathus, while the Green_C would reflect the Sierra Nevada endemic, N. nevadensis. The results provide no evidence for the genetic recognition of the most recently described morphotypes (Narcissus alcaracensis, N. segurensis, N. yepesii and N. enemeritoi), but interestingly, it recognizes as genetically distinct the populations of the Almijara range, previously identified as N. nevadensis and potentially an undescribed species that has been so far overlooked and would deserve a detailed reexamination.

What can we learn from this? The use of a source of information (genetic fingerprints) independent from morphology, allowed the scientific community to conclude that the 3-species-hypothesis of the three species (bujei, longispathus and nevadensis) is much more likely to reflect the evolutionary history of the Baetic daffodils than the single-species-hypothesis (N. pseudonarcissus). This does not mean that genetic markers are intrinsically superior to other approaches: DNA-fingerprinting methods (in particular band-pattern approaches, such as AFLP) have their own problems dealing with character homology, but when the clustering resulted from different sources of information (morphological and molecular) match, it is very unlikely that this is just by chance, and the recognition of N. bujei, N. longispathus and N. nevadensis as distinct evolutionary lineages (i.e., species) becomes strongly supported. This reciprocal illumination between the two approaches is the key to species delimitation with the best scientific guarantees. What are the consequences in terms of species conservation? As it was said before, if a territory hosts an endemic species, the responsibility to preserve the good condition of ecosystems becomes critical, because a negligent (or absent) environmental policy would result in the irreversible extinction of the taxon.

Acknowledgments

The idea of this post was inspired by discussions with Jesús Robles (@subbaeticus) and José A. López (@jalesp) on recent taxonomic changes within daffodils. They also gave permission for the use of their photographs.

References

- Medrano et al. (2014). Population genetics methods applied to a species delimitation problem: endemic trumpet daffodils (Narcissus Section Pseudonarcissi) from the Southern Iberian Peninsula, International Journal of Plant Science , 175 (5) 501-517. DOI: 10.1086/675977 ↩

2 comments

[…] Espainiako hego-ekialdeko nartzisoak baliagarriak dira adibide gisa, Rafael Medinarentzat Endemic daffodils and natural heritage […]

Gracias por el excelente post y por divulgar nuestro estudio. No lo he visto hasta hoy, y ademas llegué aquí por pura ‘serendipity’