On scientific co-authorship (2): An economic diversion, Ronald Coase’s theory of the firm

On scientific co-authorship (2): An economic diversion, Ronald Coase’s theory of the firm

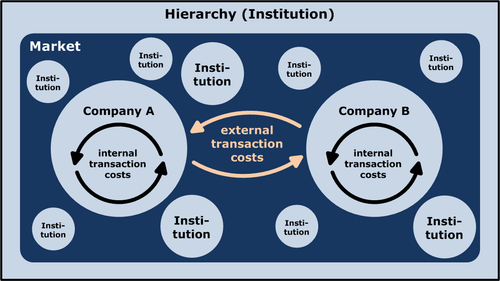

Let me leave aside for a moment our talk about scientists and papers, and bring up a topic that, at first sight, might seem totally unconnected: Ronald Coase’s economic theory about the firm and the allocation of property rights. As in the case of the problem we mentioned in our last entry (why scientists share the authorship of papers, if their academic merit is going to be assessed in function of the individual contribution each one has made to the collective stock of knowledge?), Coase’s theory also starts up from what is a seemingly economic paradox: in principle, nothing could seem more essential to the capitalist system than private firms and the free market, but the truth is that the enterprise actually constitutes a complete suspension of the market mechanism, for, while firms compete against each other in buying and selling their products to other firms, consumers or institutions, and this competitive process is the free market, no doubt the market rules cease to be valid within the firm, which is internally governed not by ‘the free encounter of demand and supply’, but by almost pure authority relationships between managers and employees, bosses and workers. The boss doesn’t go to the assembly line and asks for how much dollars are each worker willing to fix the next screw, and then buys the next item of screw-fixing to the worker who accepts a lower price. What the workers have really sold is their time and competence, that will be used by the managers (within the limits of the contract and the laws) according to what the latter decide to order at every moment. But, if it were true that free market competition guarantees that the best possible product is sold at the lowest possible price, it would be irrational to produce something by means of a system of authority relations, instead of leaving every part of the process to the ‘pure’ competitive market.

After all, corporations buy some things in the market, use them and transform them into others within the physical or institutional limits of the firm, and sell these products in the market again; and the crucial fact is that every one of the processes that takes place within the firm, could be bought instead, i.e., could be ‘externalised’ (for example, instead of having employees devoted to making tyres, a car manufacturer can buy the tyres to other company). The question is, if the free market is so efficient, why do firms not buy in the market everything they need? Why do they not externalise their whole production process? Which means, obviously, why do firms exist at all, instead of the capitalist economy being simply an aggregate of ‘atomic’ market exchanges?

Ronald Coase, in his 1937 epoch making (and not co-authored) article “The Nature of the Firm” 1, pointed to transaction costs as the explanation of this paradox. Though market exchange tends, thanks to competition, to minimise the costs of production of goods and services, the process of getting producers and users into contact, the dissemination of information about the items, and even the process of deciding what to purchase and to whom, are costly in themselves; the concept of ‘transaction cost’ covers all these heterogeneous types of costs not immediately associated with production itself. And, as it happens, when taking into account not only the cost of producing a good by an external agent, but also the costs of finding out the best offer, of negotiating the purchase, and so on, it can be the case that it is cheaper for a firm to carry out by itself the production of that good.

This theory, with all its developments in the decades following the publication of Coase’s paper, not only explains the existence of firms, but also their limits, i.e, their size. For when transaction costs for some goods tend to decrease, it would be better for a firm to externalise their production, and hence become ‘smaller’ (i.e, needing less workforce, or contributing with less added value to the whole economy), to the benefit of other firms that will now carry out that part of the production process. In a later paper 2, Ronald Coase provided a similar analysis for the explanation of the limits of property rights in general: in the absence of transaction costs, how are property rights allocated would be irrelevant, in the sense that the agents would always exchange those rights in such a way that the one who can make the most profitable economic use of one right will end buying it; but when the exchange of rights is costly in itself, then some distributions of rights are economically more efficient than others.

What has all this to do with our argument about co-authorship? I suggest that, though there is not an exact analogy between the two cases (different economic processes ‘sticking together’, so to say, within a single firm, and different contributions to scientific knowledge also ‘sticking together’ in a co-authored paper), there are two important similarities. In the first place, both in the case of Coase’s arguments and in the co-authorship case, we have a distribution mechanism (the free market and the recognition for discoveries, respectively) that seems to work apparently well, but that is ‘blurred’ by some institutional arrangements (private firms, and co-authorship) that seem to go against the working of those mechanisms. In the second place, as I’ll try to show in the next entry, the case of co-authorship can be convincingly explained by reference to the benefits brought about by a wise distribution of research efforts and (intellectual) property rights.