The economic consequences of overconfidence

The economic consequences of overconfidence

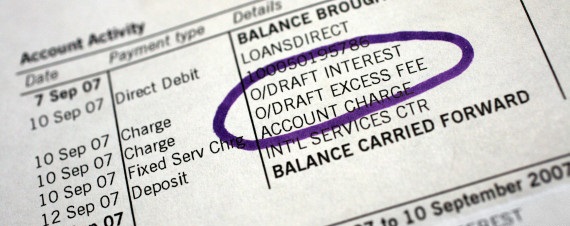

I consider an offer for a gym membership and decide to accept it after being overconfident that I will use it regularly, but in the end I will not. In other words, I overvalue the offered contract. The opposite is also possible, for instance, I may undervalue car insurance because I underestimate the likelihood of filling a claim. Overconfidence may take different forms. One is overoptimism, like when we overestimate our abilities to commit ourselves to fulfill a task (e.g., going to the gym) or to pay attention to the many details of a contract (e.g., knowing the balance in our checking account at all times to avoid overdraft fees). Even if we are not biased in estimating the average use of a service, we may be biased in estimating the variance. This overprecision is a second form of overconfidence.

Psychologists have documented the overconfidence for many decades, but if we are interested in specific consumers’ overconfidence in the market place, we must go beyond the anecdotal evidence to more recent research. Grubb (2015) [1] reviews the field data and lab experiments on the topic to find that indeed consumers are systematically overconfident. Furthermore, studies show that overconfidence does not go away easily. Some research finds that learning can be mitigated with appropriate feedback, but that competition may not give firms an incentive to provide this feedback. Further, lab experiments show that the feedback consumers receive in practice is ineffective, while field studies show that there is not enough learning to avoid mistakes (e.g., choices improve slowly or lessons are forgotten). After this, Grubb (2015) 1 addresses the next three questions.

1. What will firms do to exploit consumers’ overconfidence.

One strategy for firms to take advantage of consumers’ overconfidence is to reduce the up-front payments and to increase the price per use whenever buyers underestimate consumption. For instance, suppose that one consumer is paying a €2 fee and €1 per unit of consumption. If she uses two units she will end up paying €4, but if she mistakenly thinks that she will use just one, she anticipates paying only €3. Now, if the firm changes its price policy and charges €0 fees, but €3 per unit, the consumer will expect to pay €3, and will be indifferent, but in reality she will be paying €6. When consumers’ overestimate usage, the incentive is the opposite: to increase the up-front payment and discount marginal prices.

An important sophistication of the above strategy is the three-part tariff (a fixed fee plus zero or very low price for the first units and a higher price thereafter). However, this kind of tariffs is also compatible with price discrimination (charging different average prices to different types of consumers) with unbiased consumers. A careful analysis is needed to discriminate between the two hypotheses. Grubb (2009) 2 studies precisely this and shows that the observed patterns are inconsistent with the price discrimination hypothesis and are better explained by overconfidence.

One of the most important aspects of this strategy of complex pricing is that it survives even in very competitive markets. To see that consider the following example. Cellular services that have fixed cost of 40€ and a marginal cost of 10 cents per minute. Consumers’ valuation is 45 cents per minute up to a satiation point (100, 400 or 700 minutes with equal probabilities), but they are overconfident and believe the satiation point is 400. If prices are equal to costs (the case of efficient, competitive markets) each consumer expects a benefit of 400x(0.45-0.10) – 40 = 100€ (the term 0.45-0.10 is the difference between the value for the costumer and the price.) However, this situation cannot be an equilibrium: a firm can offer a contract with an up-front fee of €60, 400 minutes free of charge and 45 cents per minute after that. This way consumers expect to have a benefit of 400×0.45 – 60 = €120, but in reality they will have only €75 (100×0.45 + 2/3x(400-100)x0.45 +1/3x(0.45-0.45) – 60), while the firm will make €25 more.

2. Which are the welfare consequences of overconfidence.

Consumes that get a high utility from the contract will benefit from competition, as lower (alt., higher) prices will always mean same utility at a lower (alt., higher) price. With overconfidence, however, consumers for whom the expected benefits are not too big, a higher price may mean that they do not sign the contract, which may be better that signing the contract to end up paying more than expected because overconfidence. Thus, policies aimed at protecting consumers from overconfidence may have little effect if competition makes them to engage in non-efficient contracts. It can be shown, however, that consumer harm is limited when the pass-through rate is high (the fraction of the cost that is passed-through to consumers as a price increase) and market demand is very inelastic (buyers do not react much to changes in prices).

If rational consumers are present, the overconfident consumers may be subsidizing them. An example can explain this: Overconfident customers may pay €100 of overdraft fee in a checking account. If all were like that, competitive banks would price checking accounts €100 below cost and recover the money in overdraft fees. If 50% are like that, and 50% are rational, the banks will charge accounts €50 below cost to all of them. Thus, the rational costumers are being subsidized. Stango and Zinman (2009, 2014) 3, 4 estimate that, in the US USD32 billions in fees paid by less than half of account holders. Furthermore, because the ones that pay are of lower income, this is regressive price policy.

3. Which are the implications for public policy.

As we have seen, the disclosure of contract terms is not enough. In cellular services, for instance, three additional disclosure policies can be implemented: (i) the seller could disclose the average monthly bill across all existing customers of the plan, (ii) if there is already a relation, the seller can provide the buyer with an estimate based on past behavior, and (iii) sellers can let buyers share their use and billing history with third parties to find the best plan in the market.

A second policy is the disclosure to aid contract navigation. For instance, in cellular phone services, EU and US consumers must be alerted to roaming rate upon crossing national borders, and US consumers must be alerted as they approach or exceed usage allowances. Such disclosures can solve the problem of attentiveness. Extending it to retail banking could have substantial benefits.

Finally, some price regulation may be tried, although it requires too much information to be practical. However, some practices can be averted, like excessive penalties for deferring small amounts. Other regulations, like banning three-part tariffs may have some drawbacks.

Anticipating firms’ reactions is an important part of any policy. The US phone companies were required to alert costumers when they approached usage allowances, but, in the end, the firms’ response with monthly fees increases offset all the expected consumers’ benefits. By contrast, when a similar policy was used for credit cards, the rebate made consumers better off by USD11,9 billion per year. The reason of this difference has to do with the inelastic demand of phone services and a high pass-through rate near 1. The case in the credit cards is just the opposite, with almost no pass-through of changes in credit card lenders’ costs of funds to credit card interest rates.

References

- Grubb, M.D. 2015. Overconfident consumers in the marketplace. Journal of Economic Perspectives 29(4), 9–36. ↩

- Grubb, M.D. 2009. Selling to overconfident consumers. American Economic Review 99(5), 1770–1807. ↩

- Stango, V., and Zinman, J. 2009. What do consumers really pay on their checking and credit card accounts? Explicit, implicit, and avoidable costs. American Economic Review 99(2), 424–29. ↩

- Stango, V., and Zinman, J. 2014. Limited and varying consumer attention: evidence from shocks to the salience of bank overdraft fees. Review of Financial Studies 27(4), 990–1030. ↩

2 comments

[…] Posted in Noticias, Humanities & Social Sciences, Economics | 0 comments […]

[…] 画像引用元:mappingignorance […]