MI weekly selection #541

Octopus DNA helps scientists resolve geological mystery

Scientists analyzed the genetic history of an octopus species living in the Antarctic to confirm a theory about when the West Antarctic ice sheet last collapsed. The Turquet’s octopus has different populations separated by the West Antarctic ice shelves today, but the creature’s family tree indicates that the populations last intermingled around 125,000 years ago when the massive ice sheet likely collapsed.

Full Story: CNN

Reindeer do more than pull a packed sleigh

Reindeer may help prevent climate change from being even worse in the Arctic by eating and trampling woody shrubs, which can actually trap heat and accelerate warming of tundras and boreal forests. “It’s a preliminary finding, but it appears that carbon release from the undergrowth may interact with snow depth when reindeer had been excluded for several decades in an area in the far north of Finland,” said researcher Noora Kantola.

Full Story: BBC

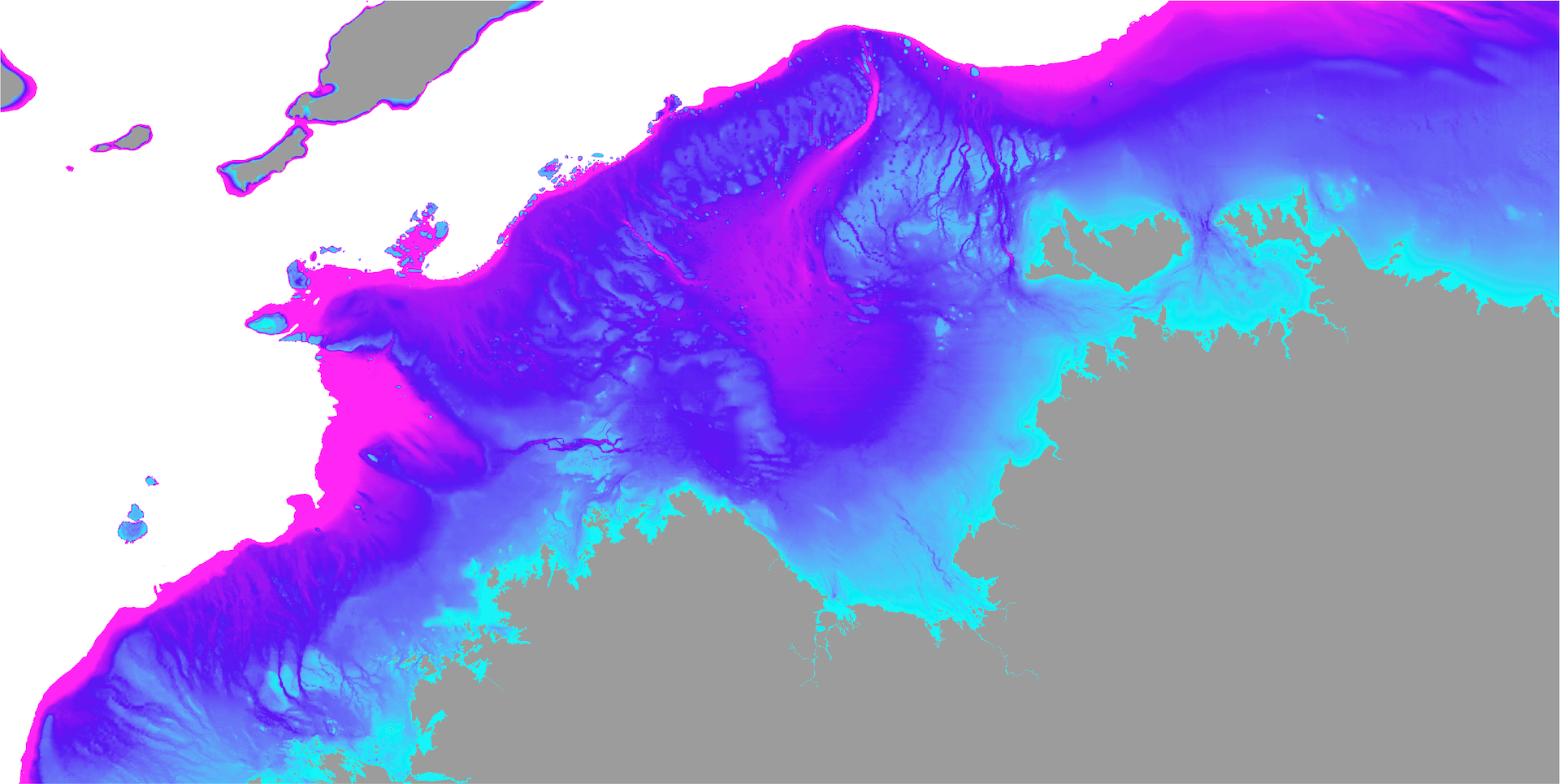

Habitation of now-drowned part of Australia

A growing body of archaeological evidence indicates that First Nations people once occupied the northwest continental shelf of Australia before rising sea levels submerged the area. The team projected past sea level data onto high-resolution maps to understand how the landscape changed over 65,000 years, and they note that the drowning of the land is also recorded in the oral histories of First Nations people.

Full Story: The Conversation

As insects decline, some plants are self-pollinating

French wild pansies are adapting to pollinator decline by “giving up” on insects and self-pollinating, producing smaller flowers and less nectar. Pierre-Olivier Cheptou, one of the study’s authors, says the plants’ strategy “works in the short term but may well limit their capacity to adapt to future environmental changes.”

Full Story: The Guardian

Clay bricks reveal ancient Earth’s magnetic field

Scientists analyzed the iron oxide grains of 3,000-year-old bricks from ancient Mesopotamia to confirm a strange anomaly in Earth’s magnetic field. The minerals found in clay bricks, which were inscribed with the names of Mesopatamian kings, reveal a signature from Earth’s magnetic field when they were heated, providing evidence of the anomaly when the magnetic field was unusally strong between 1050 and 550 BCE.

Full Story: Live Science