The filament era of the early universe

The filament era of the early universe

One of the most striking discoveries made by the James Webb Space Telescope, together with earlier observations from the Hubble Space Telescope, is that many galaxies in the young universe look very different from those we see around us today. Instead of graceful spiral disks or rounded ellipses, a large fraction of galaxies observed when the universe was only a few billion years old appear strongly elongated, more like stretched rods than flattened disks. At first glance, this seems puzzling. Why should the earliest galaxies prefer such unusual shapes?

A recent study 1 offers a compelling explanation rooted in how galaxies grow within the cosmic web. Rather than pointing to exotic new physics outright, the research shows that these elongated shapes arise naturally from the way matter flowed into young galaxies along long, smooth filaments in the early universe.

How structure forms on the largest scales

After the Big Bang, matter was not distributed perfectly evenly. Tiny variations in density grew over time under gravity, forming a vast network of filaments and knots known as the cosmic web. Galaxies form at the intersections of these filaments, where gas and dark matter accumulate. Dark matter, though invisible, dominates the mass budget and provides the gravitational framework that guides this process.

For many years, astronomers assumed that young galaxies would quickly settle into rotating disks once they collapsed, with mergers and interactions later transforming some of them into more rounded shapes. However, deep imaging surveys with Hubble, and now with Webb, have consistently found that in galaxies formed less than two billion years after the Big Bang elongated ones are common, and in some samples they even dominate.

Comparing simulated and observed galaxy shapes

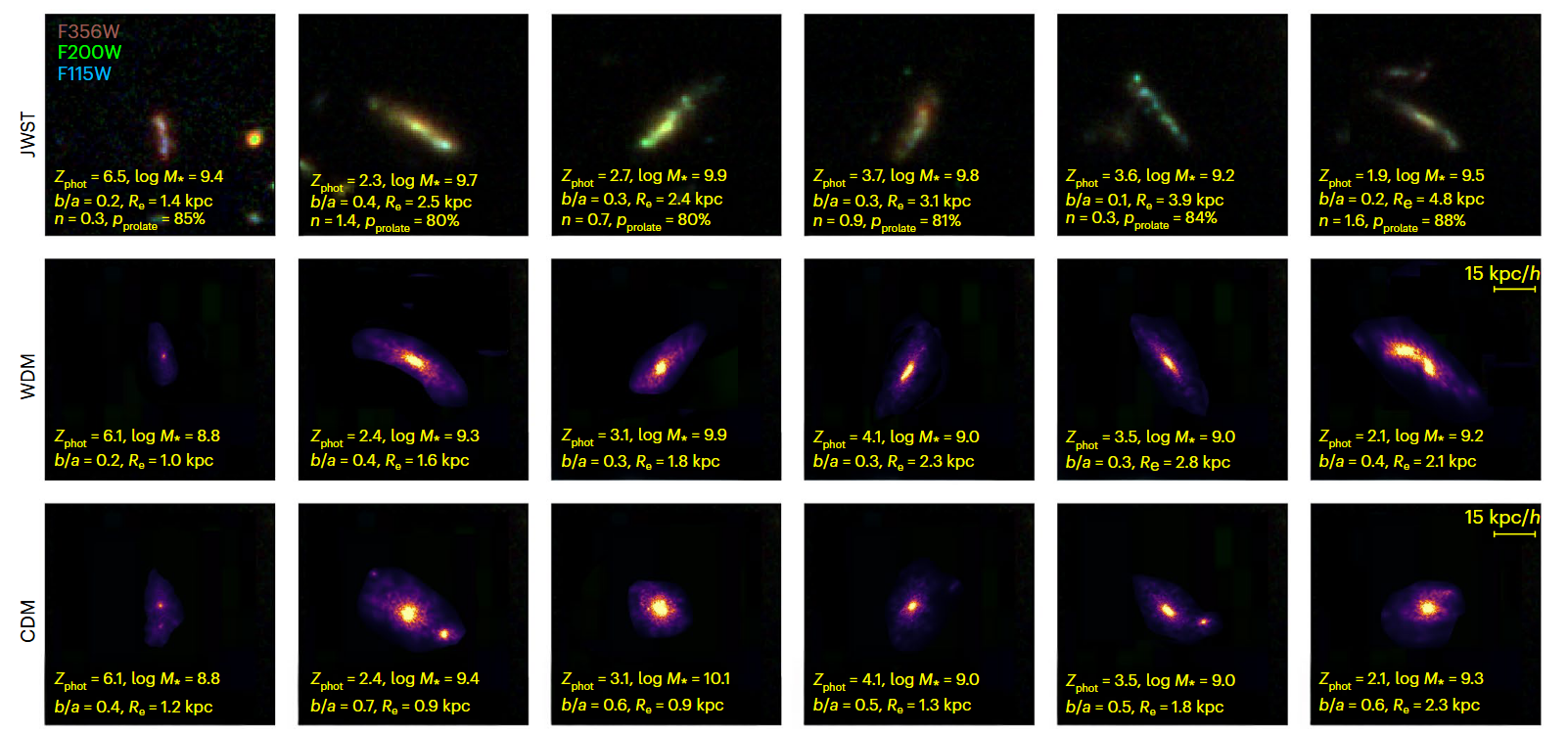

The new study tackles this puzzle by combining these observations with detailed cosmological simulations. The authors simulate the formation of galaxies within a representative patch of the universe, following both dark matter and ordinary gas as they evolve under gravity, cool, and form stars. Importantly, the simulations are analyzed in the same way as real observations, allowing a fair comparison between simulated and observed galaxy shapes.

What emerges from this comparison is a simple but powerful picture. In the early universe, the filamentary structure of the cosmic web is especially prominent. Gas does not rain down onto young galaxies from all directions equally. Instead, it streams in preferentially along one or two dominant filaments. When most of a galaxy’s mass is assembled through such highly directional inflow, the stars that form trace this geometry. The result is a galaxy that is intrinsically elongated, or “prolate,” stretched along the direction of the feeding filament.

The simulations show that when mergers are rare and growth is dominated by smooth accretion, elongated shapes are the natural outcome. Only later, as the universe evolves and mergers become more common, do galaxies tend to relax into rounder spheroids or rotationally supported disks. As a side note, one key strength of the study is its careful treatment of geometry. Galaxies are observed in projection on the sky, so a three-dimensional object can look very different depending on the viewing angle. The authors therefore infer the intrinsic shapes of galaxies statistically, using large samples and comparing projected shapes with simulated three-dimensional ones. This analysis shows that the observed galaxies are genuinely elongated in three dimensions, not merely thin disks seen from the side.

The nature of dark matter

What does this tell us about dark matter? Indirectly, quite a lot, but with important caveats. The standard, widely studied cosmological model is Cold Dark Matter (CDM), where dark matter consists of massive, slow-moving particles that cluster readily under gravity. Alternatives include Warm Dark Matter (WDM), made of lighter particles that move somewhat faster and tend to smooth out small-scale structures, and wave or fuzzy dark matter (ψDM), where quantum wave effects become significant on galactic scales. These differences might seem subtle, but they have dramatic consequences for how matter organizes itself in the early universe.

The results demonstrate that early galaxy shapes are sensitive to how smooth, coherent and uninterrupted filaments are. In that sense, galaxy morphology becomes a probe of the underlying dark matter-driven structure. However, the authors are careful not to claim that their findings point to warm dark matter ruling out the standard cold dark matter model. Similar filamentary growth can occur within a CDM framework, depending on how gas physics and feedback are modeled.

A filament era

The real significance of the work lies in what it reveals about early galaxy formation. It shows that the first galaxies did not simply resemble scaled-down versions of present-day disks. Instead, they were shaped by a phase of cosmic history in which smooth, directional inflow along filaments dominated over chaotic merging. This “filament era” naturally produced elongated stellar systems, setting the initial conditions from which later galactic diversity emerged.

As Webb continues to survey the distant universe with increasing depth and resolution, astronomers will be able to test this picture more rigorously. Future observations may even detect the filaments themselves through faint emission from gas and stars, directly linking galaxy shapes to the cosmic web that feeds them.

Author: César Tomé López is a science writer and the editor of Mapping Ignorance

Disclaimer: Parts of this article may have been copied verbatim or almost verbatim from the referenced research paper/s.

References

- Alvaro Pozo, Tom Broadhurst, Razieh Emami, Philip Mocz, Mark Vogelsberger, Lars Hernquist, Christopher J. Conselice, Hoang Nhan Luu, George F. Smoot y Rogier Windhorst (2025) A smooth filament origin for distant prolate galaxies seen by JWST and HST Nature Astronomy doi: 10.1038/s41550-025-02721-5 ↩