Speciation beyond sexuality: critiques to the biological species concept

The word “species” is one of the most relevant and controversial in the history of Biology and has often become the main topic of many books and articles. It seems that biologists can do their job quite well and understand each other as if all of them shared a tacit agreement on the meaning of this word. However, it has been frequently pointed out, that asking two different biologists for a definition of this category may raise immediately an intense debate. Before going to the point of this post I would like to remark some observations about the so called “species problem”.

First: this is not a trivial concern. Species are used as the “unit” for biodiversity assessment and many of the studies conducted in order to disentangle diversity patters at different scales and with different objectives (from phylogeography to global warming) are ultimately dependent on species-based knowledge. Second: this issue has not remained static during the past years. Several publications (e. g. 1 2) have stressed that beyond an apparent disagreement, all the “species concepts” are not incompatible, as they all try to explain why different approaches have detected the same discontinuities in the biosphere. The different concepts may be better understood as usual properties of consistent population assemblages that evolve independently, useful for their delimitation, but not as universally valid definitions. Third: changes in species delimitation and recognition is the result of an active scientific field that continuously tries to improve the accuracy of our understanding of the complexity of the tree of life (a continuum in the diachronic axis, but atomized in distinct entities in the synchronic one). This is not an easy or straightforward task at all; its instability should not be confused with arbitrariness. Fourth: Several reasons lie behind the impossibility of reaching a single universal species definition (including the limitations of language itself 3or different epistemological perspectives 4), but still, all the “popular” species concepts (morphological, biological, phylogenetic, ecological, etc) provide relevant knowledge based on scientific evidence.

The general perception of the species problem by most of the people interested in science and even by some biologists includes commonly two clichés. The first one says that the species delimitation is a subjective field rather than a scientific activity. This is a reductionist misconception of a complex challenge as stated in the observations above. The second one considers that the biological species concept (BSC) is “the lesser evil” and the most accurate species definition that we have. Just as a reminder: the BSC states that a species is a group of interbreeding populations, reproductively isolated from others. If an individual of population A mates with an individual of population B and their offspring is fertile, A and B belong to the same species. If the offspring of these individuals is a sterile hybrid or there is no offspring at all, A and B belong to different species. End of the story, right? Well, this is not that simple at all. The BSC, same as other attempts to achieve a comprehensive definition, has failed to become a universal principle. It was a meaningful contribution to the debate, but it is not intrinsically optimal.

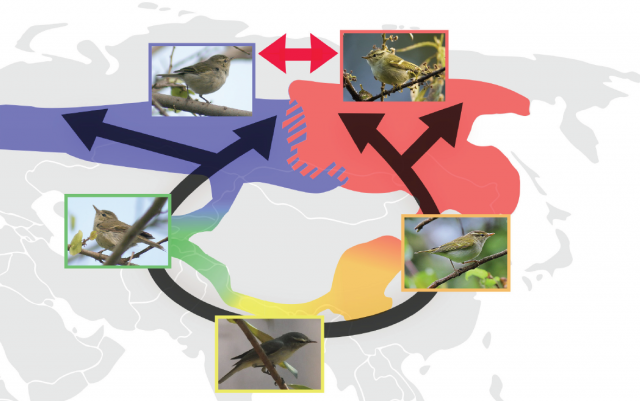

The popularity of the BSC is partly due to the work of Ernst Mayr 5 (probably its most relevant advocate, but not its author 6 as commonly thought) and its subsequent privileged position in textbooks. The pros of this definition are frequently remarked, but a more accurate introduction to the species problem should also include the main weaknesses that prevented this elegant idea to solve the secular conflict. One of the most important objections to the universality of the BSC is that reproductive isolation is not an absolute, binary condition. Biological entities often do not behave clearly when are subject to the “test” of reproductive isolation and hybridization processes have proved to be complex and widespread among very different and often distant lineages 7. Hybridization itself often behaves as the trigger for the birth of new species, and not as a barrier for gene flow. Other examples such as ring species can also prove that even within vertebrates, a group of populations may be interbreeding and not interbreeding at the same time 8.

However, the main objection to the BSC is that it cannot be applied to organisms without sexual reproduction, and thus, will never constitute a universal definition of species. (Asexual organisms do not mate or hybridize, then, BSC is unable to provide any information about their species delimitation).

A sensible question to ask at this point is whether asexual organisms can be classified into species, and it seems that they actually can. Take, for instance, the genus of bdelloid rotifers Rotaria, minute aquatic invertebrates that reproduce by parthenogenesis (eggs develop into adults without fertilization). Despite the absolute absence of males and sexual reproduction, rotifers have been traditionally sorted into species categories like any other animal. Some relevant morphological characters used for this purpose include the study of a distinct pair of “jaws” (also known as trophi). A phylogenetic study of these rotifers 9 including trophi statistical morphometrics and genome sequence analysis revealed that the traditional species delimitation corresponds with major monophyletic lineages. Each lineage bears a distinct trophi shape, determining the feeding niche of each rotifer. The compared patterns of variation (morphological and genetic) among these groups and within them rejects that they are the result of a process of neutral divergence, instead, they are better explained as the result of a adaptative divergence lead by natural selection. These groups are species, independently evolving entities whose jaws reflect ecological specialization, same as the Galapagos finches, for instance. Despite the lack of sexual reproduction, nothing suggests that these rotifer species deserve a segregated explanation for their origin.

An analogous situation can be found in the parthenogenetic weevils of the genus Naupactus [footnote] Rodriguero, M. S., Lanteri, A. A. & Confalonieri, V. A. 2013. Speciation in the asexual realm: is the parthenogenetic weevil Naupactus cervinus a complex of species in statu nascendi?. Molecular phylogenetics and evolution. [/footnote]. After the detection of a highly polymorphic genome of some of these beetles collected in South America, different coalescent-based analyses oriented to species delimitation were performed. Although these weevils also lack sexual reproduction, the analyses allowed the authors to detect at least two distinct and sympatric evolutionary units that are undergoing divergence due to natural selection. They interpret these results as the reflection of an ongoing speciation event, once again, suggesting that sexual reproduction is not a requirement for the existence of species. Reproductive isolation is usually a consequence or a trace of the occurrence of a speciation event, but clearly, not a requirement.

References

- Hey, J. The mind of the species problem. 2001. Trends in Ecology & Evolution16, 326–329 ↩

- De Queiroz, K. 2007. Species concepts and species delimitation. Systematic Biology56, 879–886 ↩

- Pigliucci, M. 2003. Species as family resemblance concepts: The (dis-) solution of the species problem? BioEssays25, 596–602 ↩

- Wilkins, J. S. 2003. How to be a chaste species pluralist-realist: the origins of species modes and the synapomorphic species concept. Biology and Philosophy18, 621–638 ↩

- Mayr, E. 1963. Animal species and their evolution. Harvard University Press. Cambridge ↩

- Wilkins, J. S. 2009. Species: a history of the idea. University of California Press. Berkeley ↩

- Abbott, R. et al. 2013. Hybridization and speciation. Journal of Evolutionary Biology26, 229–246 ↩

- Per, A. 2006. Species concepts and their application: insights from the genera Seicercus and Phylloscopus. Acta Zool Sinica52, 429–434 ↩

- Fontaneto, D. et al. 2007. Independently evolving species in asexual bdelloid rotifers. PLoS Biology5, e87 ↩