Why it hurts when somebody breaks our heart

It is interesting how we describe social rejections – betrayal, exclusion from a group or a break-up from a romantic relationship are good examples: “he was cruel with me and it was painful”, “I suffered a lot during the divorce”, etc. Why we describe them as painful situations where there is no physical contact?

If you break your arm – don´t do this it at home and without the supervision of a science communicator – you will feel pain. The lesion will be detected by the nociceptors at the injury and they will send this information to your brain through a bunch of nerves, the brain will process the information and… voilà: pain. Cool, isn´t? The interesting thing is the fact that pain is not defined as a perception but as a perceptual experience. Pain is not like colors or musical notes which can be accurately defined by objective parameters, pain is an experience. Therefore, it changes from one person to another and it depends on the context.

If we focus our attention on the physical pain, this experience has two components:

1.-A sensory component: location, intensity, duration… of the pain.

2.-An affective component: distress, suffering, etc.

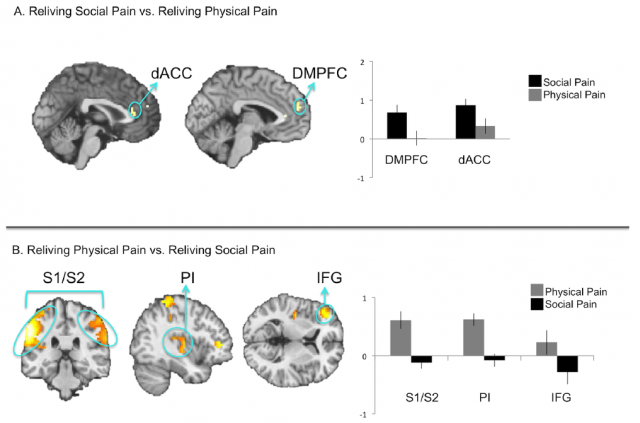

The first component: how is the pain? (strength, length, location…) it goes through one neuronal route. And the second component, the emotional part of the experience (suffering, stress, etc.) goes through another neuronal route. The sensory component of the physical pain is processed in the brain by the secondary somatosensory cortices, the inferior frontal gyrus, and the posterior insula; meanwhile, the affective component is processed, in part, by the dorsal portion of the anterior cingulate cortex (dACC), the dorsal medial prefrontal cortex and the anterior insula. So, we process physical pain using two neuronal routes.

However, we have been talking about physical pain, but… what about when somebody has fun about us or breaks our heart? Are these experiences painful? Yes, they are. They are social pains.

In social experiments with humans where the participants are exposed to social exclusion, like initially be allowed to participate in a team game and later on had been excluded from the group, the participants showed increased activity in pain´s affective structures like the dACC and the anterior insula. Furthermore, the subjects who developed greater activation in the dACC manifested stronger feelings of social distress in response to the exclusion. This situation has been shown in several studies and it indicates that social exclusion activates in our brains structures that are also activated when we suffer an injury. It´s pain. But social and physical pain are not exactly the same.

It has been proved that reliving memories of physical pain mainly activates the sensory pain system (secondary somatosensory cortices and posterior insula), not the dACC. In contrast, reliving social pain preferentially activates pain´s affective structures like the dACC. The differences in the levels of activation of the two pains pathways create the separation between physical or social pain, but both experiences activate some pain neuronal pathways. So, when someone is mean to you and you feel pain, it really hurts, even if it is not neurologically exactly in the same way as a punch in the face.

We can suffer physical or social pain. However, even in physical pain the social context is very important. For example, it is known that the physical or emotional pain caused by other person hurts more if it was known that the aggression was intentional. Also, while people can habituate to randomly delivered painful shocks to them, they are not able to habituate to the pain caused by another person who intentionally hurts them. In the other hand, people with more social support show less activity in the dACC and anterior insula, and they can stand better social exclusion in contrast with people prone to worry about rejection from other, who manifest increased activity in the affective structures. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that some socially painful experiences can change the level of activation in these neuronal regions. For example, females who had suffered a miscarriage showed a higher activity in the dACC in response to viewing pictures of smiling baby faces compared to the control group, females who had given birth to a healthy child.

Finally, social and physical pain are neurologically related and factors like inflammation, known to enhance physical pain sensitivity, also seem to increase neural sensitivity to social pain. And some painkillers appear to act as a ‘social painkiller’ too. Also, it is known that physical pain can be reduced through social stimulus like seeing a photo of your couple or holding the hand of a friend while you are going through a physically painful moment.

In summary, social experiences can literally hurt and in my opinion, we should be careful with what we say to other people. Actually, words can generate pain. But also we should keep in mind that words and social support can be a useful painkiller.

References:

Meyer, M. L., Williams, K. D., & Eisenberger, N. I. (2015). Why Social Pain Can Live on: Different Neural Mechanisms Are Associated with Reliving Social and Physical Pain. PloS One, 10(6).

Eisenberger, N. I. (2013). NIH Public Access, 74(2), 126–135.

2 comments

[…] Una rutura sentimental, del tipo que sea, suele cursar con dolor, en algunos casos mucho. Pero no es un dolor metafórico, es un dolor físico. Pablo Barrecheguren en Why it hurts when somebody breaks our heart […]

[…] Berrecheguren, P. Why it hurts when somebody breaks our heart. Mapping Ignorance. Recuperado el 2 de Abril 2019 de link […]