Nanotechnology: undermined by the patent system?

Nanotechnology: undermined by the patent system?

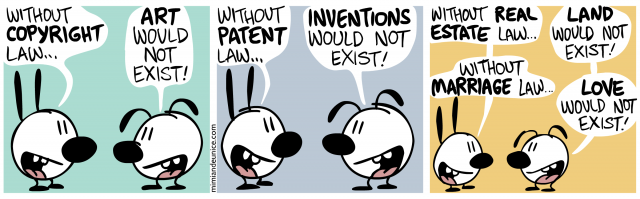

Originally, intellectual property legislation was created on the assumption that the profits derived from the monopoly of the patented inventions would encourage innovation and thus promote economic growth. This is one of many hypotheses that the vast majority of economists have ever considered as intuitive. Accordingly, it is generally believed that the patent system is partly responsible for the economic growth since the industrial revolution.1

However, it seems that the free and open-source software (FOSS) concept has seriously questioned this economic preconception. Unlike commercial software, often proprietary and working with code that anticipates the user demands, FOSS is a decentralized, participatory and transparent system of software development in which the innovation process has proved efficient through collaborative effort.

This apparent deviation from the principles of Economics arouses serious doubts about the role of intellectual property (IP) legislation as a necessary tool to provide innovation. In fact, a growing number of scholars point out that it could be quite the opposite. The economists Michele Boldrin and David K. Levine maintain in their highly recommendable (and free) work “Against Intellectual Monopoly“ that most innovations have taken place without the benefit of intellectual monopoly. Moreover, they claim that in a cross country comparison, the less competitive and more inefficient an industry is, the stronger is its demand for monopolistic protection from new competitors, remarking that intellectual monopoly and fair competition rarely come together.

They illustrate in detail, with a great number of examples from different industries and sectors, the intense pace of creation occurring in the absence of copyright. It is worth reading the case of the Watt’s steam engine as a case study of Intellectual Property inefficiency. James Watt and his business partner Matthew Boulton, a rich industrialist very well connected at the British Parliament, managed to get their patents extended from 1775 to 1800. During that time, their activity consisted primarily of inhibiting competition by the exploitation of the legal system rather than by the development of the steam engine. This way of suppressing innovation is the so-called rent-seeking behaviour, and it is more usual than we might expect. The inefficiency of the steam power monopoly is perfectly exemplified by the Hornblower’s engine, a significant improvement over Watt’s one (due to the introduction of the “compound engine”) that was completely blocked in court because he made use of the Watt’s separate condenser. After Watt’s patents expired, the Hornblower’s engine was the basis for further steam engine development, and not Watt’s. Furthermore, once the Boulton and Watt monopoly came to an end, the manufacture and efficiency of engines really experienced a great development, turning steam power into the driving force of the industrial revolution.

The damaging effects of intellectual monopoly are fully visible in several research fields such as agriculture and pharmaceutical industries, causing human suffering and death which can be prevented by known but not available technologies. In this context, there are numerous groups, universities, companies and individuals who are claiming to embrace the open source paradigm in order to guarantee free access to critical information. One field in which the current IP system could be especially harmful is nanotechnology, as it promises to have a huge impact in almost every area of knowledge in the near future.

In NanoToday Dr. Joshua M. Pearce, Materials Engineer from the Michigan Technological University, drew attention to the “intellectual property tragedy” currently occurring in the field of nanotechnology2. According to him, nanotechnology development is being already hindered by a “dense patent thicket of overlapping claims and rights”.

The main IP inefficiencies to be aware of in the field of nanotechnology are properly listed in Dr. Pearce’s article. First of all nanotechnology, unlike many other areas of knowledge at their times, is growing in a fully developed IP system where many fundamental research has been locked down preventing fair competition. Due to its interdisciplinary nature, this intellectual monopoly over the building blocks of nanotechnology can dramatically affect many different fields of knowledge such as medicine, biotechnology, materials science, and so forth.

Secondly, when it comes to bring to market a new product based on proprietary nanotechnology it is mandatory to go through a huge amount of previous patents in order to acquire the necessary licenses and avoid legal issues. Most of the time this task is outsourced, so that a considerable investment of time and money will be needed, obviously depleting the investment on research and development of the new product. Consequently, as many fundamental research in nanotechnology is already patented, the development of more complex technologies has enormous transaction costs unbearable for modest research labs.

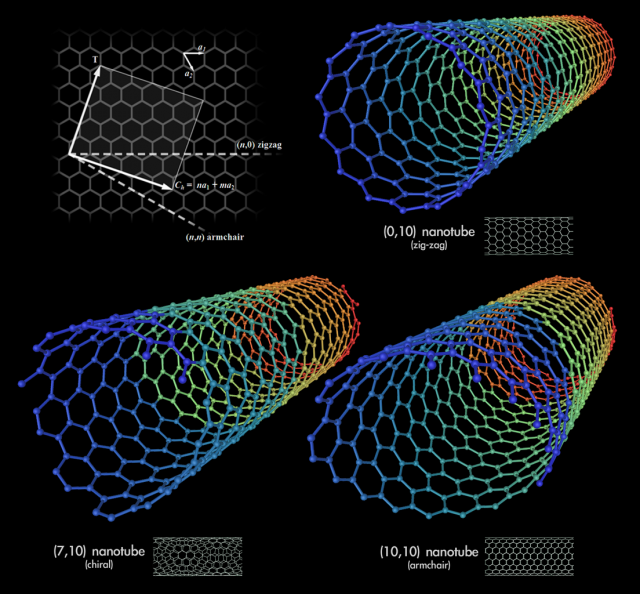

The case of carbon nanotubes (CNT) is paradigmatic. Discovered in 1991 by Sumio Iijima, the key patents on CNT’s production belong to two huge corporations, NEC and IBM. It goes without saying that every new item based on CNT has to deal with a hodgepodge of licenses, claims and rights. Actually, it has become a sort of lawyer’s trickery on novel vocabulary avoiding the CNT patented words, comprising nanofibers, nanowires, nanocylinders, rolled graphene, and so on. As a result, innovation is being replaced by legal battles.

This bureaucratic mess together with the complexity of the underlying science lead to absurd situations, such as claiming for patent when a new behaviour of a certain material is identify, preventing others from working with that material. Moreover, many of these patents are not used whatsoever, but only remain useless, locking lines of inquiry.

Dr. Pearce also remarks a quite sensitive point. Most of the fundamental research in nanotechnology is nowadays carried out with public funding, and accordingly, the benefits of this research should be returned for the benefit of society. It doesn’t seem right that society has to pay twice for these research discoveries. In this regard, US government has recently announced that all federally funded research should be open-access.

All things considered, it seems that intellectual monopoly in nanotechnology can seriously impair its development for decades. Dr. Pearce proposes an open-source model similar to that of software in order to speed innovation, lower transaction costs and give nanotechnology the opportunity to meet its full potential as soon as possible. This paradigm is becoming a reality in many other fields, allowing innovation in areas that are not commercially feasible, but socially necessary.

As Boldrin and Levine would say, the idea of a free and open-source nanotechnology is not talking about Gardens of Utopia, but about the practical experience of thriving markets in the absence of intellectual monopoly.

References

- M. Boldrin, D. K. Levine, What’s Intellectual Property Good for?, Revue économique (2013) 1, 29-53. PDF ↩

- Pearce J.M. (2013). Open-source nanotechnology: Solutions to a modern intellectual property tragedy, Nano Today, 8 (4) 339-341. DOI: 10.1016/j.nantod.2013.04.001 ↩

5 comments

[…] Nanotechnology: undermined by the patent system? | Mapping Ignorance. […]

The intellectual property is indeed a very serious problem for the advance of Science today. I really hope initiatives such as the open-access policy embraced by the US can help to smooth out a bit the situation.

From what I know, UK also forces the publicly funded research to be published in open-access journals, and most of the traditional journals are now offering the option of releasing papers as open-access material in response to this policies. That’s a good sign.

Regarding copyright and intelectual production there is a very nice post here, at MI

https://mappingignorance.org/2013/04/16/copyright-protection-and-the-number-of-intellectual-works/

Excellent entry. But note that Boldrin and Levine are not the only economists warning about the excesses of IPR. As a matter of fact, it has been long recognized that there is a trade-off between protecting innovations and the new innovations that can stem from the original invention. As as illustration, chech section 1.8 in the European Competitiveness Report 2011 (online) and references therein.

Only one problem: as John Turner and I document in our Journal of Law and Economics paper, paper, “Strong Steam, Weak Patents” etc., the conventional belief, repeated by Boldrin and Levine, that Watt’s patent held back high pressure steam, isn’t true.