Skepticism, a short uncertain story (3): medieval doubts

Skepticism, a short uncertain story (3): medieval doubts

Perhaps you ignore that the most influential philosopher of the early Middle Ages did not really exist. This Zenoan paradox is explained by the fact that the writings of this philosopher were falsely attributed to a different, and much more authoritative person, and hence, after the counterfeit was established about one thousand years later by humanist Lorenzo Valla and others, basically all Medieval philosophers (or it’s better to say theologians) were quoting and discussing the work of someone who was not the one they believed. Since we have no idea of the identity of the real author of those books, history has imprinted the name of the fake author in the philosophical tradition, and so you must not be surprised when finding a reference to someone weirdly referred to as ‘Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite’.

We know basically nothing about the biographies of neither the ‘real’ Dionysius nor the ‘fake’ one. The former is supposed to have been one of the first converts Saint Paul made in his visit to Athens, according to the Acts of the Apostles; the ecclesiastical tradition asserts that he was one of the judges of the Areopagus (a high court that sat on top of a big rock at the foot of the Acropolis) and that, once converted to Christianism, became the first bishop of Athens, but there is no way of knowing whether anything of that is true, nor even the existence of Dionysius himself. Instead, our friend ‘Pseudo-Dionysius’ lived (probably in Syria) surely more than four centuries after the one he took his pseudonym from, and composed a series of books that claimed to have been written by Paul’s Athenian disciple. It is not totally clear whether this ‘claim’ was intended by the real author as a mere literary figure, more or less common in Antiquity, or as a simple and pure attempt to deceive the readers about the identity of the author, and hence about his ‘authority’ (see Bart Ehrman’s book Forged, for a wonderful study of this fraudulent practice in early Christian writings, including several New Testament books). The fact is that, already from the early sixth century C.E. onward, not much later that they were composed, and probably even during the life of their real author, his works were already being uncritically cited as belonging to the ‘old’ Dionysius; so, even without the attempt to deceive, deception occurred. Just to give an impression of how deep the deception was, we can consider the fact that Pseudo-Dionysius is the second most cited philosopher in the works of Thomas Aquinas (13th century), only after Aristotle. Pseudo-Dionysius started to be influential in the West, however, around three centuries after his death, when the Byzantine emperor Michael II gifted a manuscript of his works to Charlemagne, who in turn donated it to the monastery of St. Denis in Paris (by the way, it also circulated the conjecture that the real author of the works was this other Dionysius, the 3rd century ‘apostle of the Gaul’), a manuscript that that was soon translated into Latin.

We know Pseudo-Dionysius was a fake thanks to philological analysis: not only important aspects of his thought, but even full paragraphs of his texts, come from an author four centuries younger than the ‘original’ Dionysius, the Neoplatonic Proclus, probably the last important figure in Ancient, non-Christian philosophy, who was the leader of the Academy in Athens during the second half of the 4th century C.E. Proclus died in 485, and the first known references to Pseudo-Dionysius (or to his preserved books, collectively known as Corpus Areopagiticum) date from about 40 to 50 years later, so our fake author must have lived around the turn of the 4th and 5th centuries, and probably was himself a disciple of Proclus, and a student in the Platonic Academia.

But Pseudo-Dionysius is important in a history of skepticism not, of course, for being an example of how we must doubt even of philosophical authorship, nor because of his thought really being an example of skepticism in the Sophistic or Pyrrhonian traditions we met in the previous entries of this series. After all, Pseudo-Dionysius was a Christian thinker, author, among other things, of a big part of the celestial mythology about the number of heavens and classes of angels you perhaps are familiar with (and which influenced, among other works, Dante’s Divine Comedy): Seraphim, Cheribum and Thrones; Dominions, Virtues and Powers; Principalities, Archangels and Angels. We wouldn’t classify as a skeptic someone that seriously explains that these ‘spheres’ or ‘choirs’ of celestial beings exist. But Pseudo-Dionysius has not passed to the history of philosophy mainly for his taxonomic work in angelic zoology, but for what later has been known as ‘negative theology’ (also known as ‘apophatic theology’; apophasis is a rhetoric figure consisting in mentioning someone or something by stating that one will not talk about him or her, something similar to Spanish PM Rajoy’s alluding to corrupts members of his party as ‘those people I have nothing to say about’).

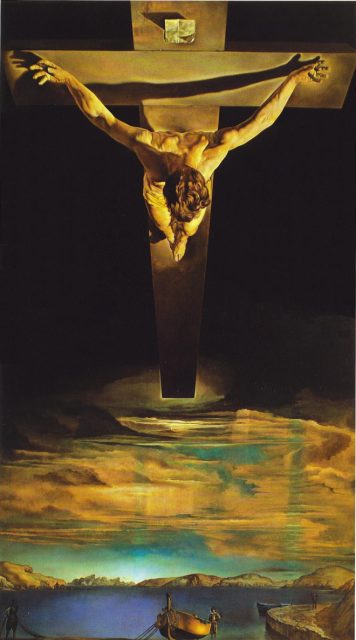

According to Pseudo-Dionysius, in his book entitled On Mystical Theology, God is absolutely transcendent to human reason, language and knowledge, in a similar way to the aporias Parmenides and his disciples found when trying to talk about Being (recall the first entry of this series). This means that we cannot assert absolutely anything about Him, but we can only negate, for each possible predicate we could think of attributing to Him (say, ‘omniscient’, ‘living’, ‘creator’, even ‘being’, i.e., ‘existing’), that He has the property denoted by that predicate. I.e., we can only say what God is not, and what He is not is just… everything: He is not omniscient, He is not living, He is not powerful, He just is not. God, for example, is no more spirit, son or father than it is ‘soft’ or ‘asleep’. These negations, however, are to be distinguished from ‘privations’: a privation is simply the absence of a given predicate that could be present. The absence of the predicate is opposed to its presence: ‘lifeless’ is opposed to ‘living’. But when we say that God is not ‘living’, we do not mean that He is ‘lifeless’, for actually He is not lifeless either. God is just beyond the lifeless as well as beyond the living. For this reason, Pseudo-Dionysius says that our affirmations about God are not opposed to our negations, but that both must be transcended: even the negations must be negated. This ‘negation’ parallels the only possible human experience of god, that Pseudo-Dionysius exemplifies with the figure of Moses on the mount Sinai, and that describes it as “silence, darkness, and unknowing”. This theory opened the way to the rich mystical tradition in Christianity (recall John of the Cross’s verses, more than a millennium later: “lleguéme donde no supe / y quedéme no sabiendo, / toda ciencia transcendiendo” – “I came into the unknown / and stayed there unknowing / rising beyond all science”). But, skeptic or not, it was most influential as a signal of the limits of human reason to understand ‘the Absolute’, and as a reminder that all theology is, in the end, an exploration out of those limits. Once the faith in the truth of religion (as well as the social power of the Church), became to weakening many centuries later, the existence of negative theology could start to be seen as an argument against the reasonableness of all those attempts of saying anything about God or the divine.

Needless to say, the Middle Ages were not a good time for skepticism, especially for skepticism about the dogmas of religion, but the skeptic tradition managed to survive for more than a millennium, at least under the form of something that philosophers should try to refute. Even one century before Pseudo-Dionysius, the great theologian Augustine of Hippo confessed that, before converting to Christianity, he had flirted with a fistful of philosophical and rhetorical schools, including skepticism, and devoted some pages of his work to rebut some of the skeptics’ arguments, as did many other philosophers afterwards. In doing so, he was the first one of presenting the argument that not everything can be doubted, because when one doubts, one knows for certain that he is thinking: cogito, ergo sum.

However, Medieval philosophy produced a couple of families of arguments that were later fruitfully employed by Modern skeptics (and that worried to some Medieval ones). In the first place, the work of the Arab mathematician, physician and astronomer Alhazen (10th-11th centuries C.E.) established for the first time, in his important work on optics, that visual appearances are created by our cognitive organs, or stated in other terms, that perceptions, even the simpler ones, are always constituted by inferences, and hence are not anything like a ‘direct unity’ with the perceived object (as was defended, e.g., by Aristotle’s theory of perception). In the second place, the idea of God’s omnipotence seemed to entail, according to some philosophers, that He could deceive us if He wants, even when we are feeling the greatest of the certitudes, in seeing something in front of us, or in understanding the proof of a mathematical theorem. But, as it is well known, it was later philosophers who were to extract more interesting conclusions about these ideas.

REFERENCES

Ehrman, B., 2001, Forged: Writing in the Name of God—Why the Bible’s Authors Are Not Who We Think They Are. HarperCollins, USA.

Lagerlund, H., 2010, Rethinking The History of Skepticism: The Missing Medieval Background, Leiden: Brill Publishing.

Stang, C., 2012, Apophasis and Pseudonymity in Dionysius the Areopagite: ‘No Longer I’, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

5 comments

Me ha parececido interesante tu artículo. Gracias al traductor de google puedo seguir tus razonamierntos en el mapping….

Me ha recordado las clases de filosofía de preu ( Tenía un buen profesor, lo recuerdo con cariño ) solo que entonces el Aeropagita no era falso y la zoología celestial ya estaba en decadencia.

Me alegro de poder seguir tus articulos.

Carlos.

I think these two sentences of yours are contradictory:

– Needless to say, the Middle Ages were not a good time for skepticism

– Pseudo-Dionysius is the second most cited philosopher in the works of Thomas Aquinas

I mean, the fact that Pseudo-Dionysius was the most influential philosopher of the early Middle Ages proves that skepticism was not such a rarity.

On the other side, ‘negative theology’ is not pure negation. It first affirms something about God, then it negates that what has been stated is The Truth about God, because God cannot be confined within spoken or written words. The best Christian theologians never forgot this essential limitation of knowledge about God. Your quoted verses of John of the Cross express this perfectly. Only mediocre theologians believed that wisdom about God could be closed in dogmatic formulations.

Whether Dyonisius or Pseudo-Dyonisius, his influence in medieval thought was beneficial and must be acknowledged, as you do.

===

A note on dates. You write:

“Proclus, probably the last important figure in Ancient, non-Christian philosophy, who was the leader of the Academy in Athens during the second half of the 4th century C.E. Proclus died in 485, and the first known references to Pseudo-Dionysius (or to his preserved books, collectively known as Corpus Areopagiticum) date from about 40 to 50 years later, so our fake author must have lived around the turn of the 4th and 5th centuries, and probably was himself a disciple of Proclus, and a student in the Platonic Academia.”

If Proclo died in 485, then he lead the Academy during the second half of the 5th Century, not the 4th. And so, Pseudo-Dyonisius must have lived around the turn of the 5th and 6th centuries.

Thanks for the comments and corrections.

[…] [Esta é unha tradución adaptada do artigo orixinal de 3 de xuño de 2015 Skepticism, a short uncertain story (3): medieval doubts, de Jesús Zamora Bonilla, que pode lerse nesta ligazón.] […]

[…] published by Mapping Ignorance, 06.03.2014, under the terms of a Creative Commons […]