A pulse in the Mediterranean diet

A pulse in the Mediterranean diet

Intense flavors imprint our palate at every spoonful of Asturian fabada, an unquestionable cultural hallmark of Northern Spanish cuisine. Because of the present United Nations´ international year of pulses, we are visiting here some bits of the science about a food regime particularly rich in them. Beans, lentils, and chickpeas are feeding building blocks for humans worldwide – also surrounding the Mediterranean sea, where regional food habits have been repeatedly suggested to protect against cardiovascular attacks. On the roots of this hypothesis, inhabitants in those countries would suffer from lower cardiovascular mortality compared to Northern European countries and the United States.

However, many factors beyond the diet -including cultural, socio-economic, climatic and perhaps genetic- are also unique to this particular population. Hence, whether the cause for the cardiac protection has anything to do with diet remains obscure.

To directly study that, Spanish researchers launched in 2003 one of the largest and long-lasting randomized trials published to date on dietary interventions. For almost 5 years, researchers monitored more than 7000 people aged between 55 and 80 and at high cardiovascular risk. Participants were instructed to follow either a Mediterranean diet or a low-fat control diet.

A first set of findings from this study was published in 2013 – in the New England Journal of Medicine, where researchers reported a protective cardiovascular effect for Mediterranean diet. Up to a 30 % lower incidence of a joint estimate including heart attacks, strokes or death from cardiovascular causes was observed in participants following this feeding pattern 1.

The finding buzzed. Dietary and lifestyle prevention measures for cardiovascular diseases are the crown jewel for an aging population. Around 1000 million people older than 60 are estimated to live by 2020, a scenario in which cardiovascular failure will be a prevailing death cause.

Later on, researchers expanded the range of protective effects of Mediterranean diet studying subsets of participants in the larger trial. Among other conditions, authors have shown, Mediterranean diet reduces the risk of metabolic disease, Diabetes type 2, age-related cognitive decline and breast cancer. Even a moderate consumption of wine lowers the risk of depression2.

But an essential piece of the puzzle is still missing. While the beneficial effects seem clear, the mechanism remains a mystery. What is exactly in the Mediterranean diet responsible for its protective effects? This is intriguing since the exact composition and quantities of Mediterranean diet regimes are not precisely defined – likely reflecting a culturally variable practice. But also, a lack of an identified molecular causal agent hinders the possibility to run efficacy studies through double blinded trials – the only way to rule out that the observed effects are due or not to placebo.

Randomized trials clearly showed that the protective influence of Mediterranean diet is not a black or white result. The improvement rates ranged up to 30 %, far from absolute. Would that suggest that only certain subjects are susceptible to the benefits of this food regime? To answer that question, researchers are now studying what in our organism contributes to the beneficial effects of Mediterranean diet.

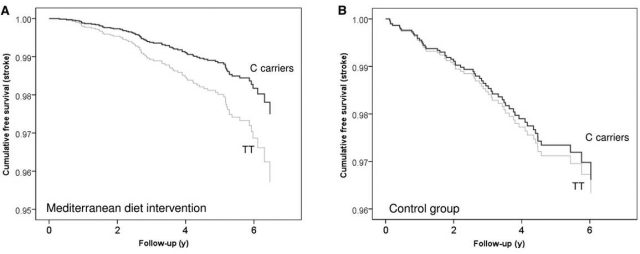

And they have already found some clues to why this diet might not exert an even influence across individuals. One specific genetic variant, only present in a fraction of people, modulates the dietary outcome 3. The variant drives a higher production of lipoprotein lipase (LPL), a protein that clears fats from the blood, and is associated with a lower mortality caused by stroke. The DNA difference disrupts the binding of a particular microRNA – a molecular switch that turns off gene expression – therefore increasing the level of LPL.

The genetic variant by itself does not drive the reduction in mortality: the effect only happens in carriers that also follow a Mediterranean diet. But it does not occur in carriers under a control diet. Likewise, people not carrying this variant do not show reduced incidence of stroke when following a Mediterranean diet. Thus, the diet might be protective only in specific genetic backgrounds.

Answering why will keep scientists busy for the next years. Meanwhile, feel free to enjoy healthy and delicious salads –better supplemented with legumes to celebrate this yearly international recognition of pulses.

References

- Estruch, R. et al (2013): Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease with a Mediterranean Diet. N Engl J Med. 368:1279-1290. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200303 ↩

- Find all the PREDIMED publications in the project’s website ↩

- Corella, D. et al (2014): MicroRNA-410 regulated lipoprotein lipase variant rs13702 is associated with stroke incidence and modulated by diet in the randomized controlled PREDIMED trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 100 (2):719-731. DOI: 10.3945/ ajcn.113.076992 ↩

4 comments

[…] En el Año Internacional de las Legumbres, José Viosca se plantea lo siguiente: la dieta mediterránea supone un menor riesgo cardiovascular; vale, pero, ¿cuál es el mecanismo? La respuesta puede estar en la presencia de legumbres: A pulse in […]

[…] En el Año Internacional de las Legumbres, José Viosca se plantea lo siguiente: la dieta mediterránea supone un menor riesgo cardiovascular; vale, pero, ¿cuál es el mecanismo? La respuesta puede estar en la presencia de legumbres: A pulse in […]

[…] A pulse in the Mediterranean diet […]

[…] Sigue leyendo en Mapping Ignorance […]