Do mannequins have anorexia?

Do mannequins have anorexia?

Anorexia nervosa is the oldest of the eating disorders. It is a serious problem with the highest mortality rate of all psychiatric disorders. We live in a epoch strongly marked by advertising and commercial references, in which different brands use shocking ads with beautiful girls and perfect guys. Whether it’s food, cars, clothing or perfumes, the sculpted bodies of the models show their slim, tall, handsome figures. Men are not alien to this image cult, and the muscular bodies, without a drop of fat, are a reference for many boys and young adults.

Under all these images there is a strong social pressure, to which adolescents and young people, as well as adults, are subjected day by day. And in that reality, the ideal body does not resemble the real body. Young people are exposed to a theoretical archetype, thin bodies, where intelligence, kindness, sympathy and other virtues do not seem to have a place. It is the cult of the body and a type in which very few people fit, with measures often extreme and difficult to achieve and maintain. We live in a society that is concerned about anorexia, but idolizes thinness as a symbol of beauty, success and perfection. In the modern developed world unrealistic body ideals are communicated both implicitly and explicitly to women. Thus, there is a growing awareness that prevention efforts against anorexia and other body image problems need to address the fashion environment and reduce promotion of ultra-thin body ideals.

Fashion stores use mannequins to present their novelties. A study published in 1992 was entitled “Could mannequins menstruate?” 1 The title was based upon the fact that women should have at least 17% of their weight as fat to have menarche and 22% to have a regular cycle. Not nonsense, this fat contains the easily mobilizable energy that provides enough ATP during pregnancy and lactation. This study used six old mannequins (from the 1920s, ‘30s, ‘50s, and ‘60s) housed in museums and the “amount of fat” was calculated using a formula that uses arm circumference and thigh circumference, two values that can be easily obtained from a mannequin. The same anthropometric measurements and calculations were made on six average sized female medical students aged 20-30 years. The calculated amount of fat of the display figures was mostly in the normal range before the 1950s but was considerably less since then and, in fact, real women of a similar body size would be so thin that they would be unable to menstruate 2. The display figures have become thinner with time and their proportions now differ considerably from those of normal young women. Moreover, woman with the proportions of a Barbie doll would be even thinner than the most modern mannequins of that group (1).

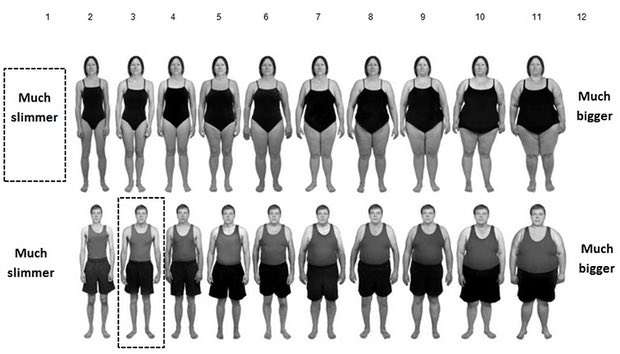

In 2017, a new study was published after surveying all national chain fashion stores on the high streets of Liverpool and Coventry 3. ‘High street’ stores were operationalized as stores located on the street that was home to the main shopping promenade area of that city. Stores were eligible to be sampled if they had at least one mannequin on display (male and/or female) and were part of a national chain (i.e. more than one store in the country). The authors opted to sample only national chains as they reasoned that this sampling approach would produce the most representative data for the size of mannequins widely used in high street fashion. The researchers visited 17 stores and got acquainted with 58 mannequins, 32 of which were “female” and 26 “male”. Their original intention was to collect anthropometric measurements of mannequins; however, they contacted all eligible retailers across both survey sites and no retailers gave permission to take anthropometric measurements. They therefore used visual rating scales to assess mannequin body size: a BMI-based body size guide rating scale and the Contour Drawing Rating scale. Two researcher assistants (1 male, 1 female) blinded to the authors’ hypotheses rated mannequins in both survey sites. All of the female mannequins in these shops had body sizes that corresponded to that of an underweight woman. They did not find a single female mannequin that was a normal body size on display. Although some retailers have reported that they now use more appropriate sized mannequins, this study demonstrates that, at least in the British shops studied, this is not true. By contrast, the average male mannequin body size was significantly larger than the average female mannequin body size. Only 8% of male mannequins represented an underweight body size. The conclusion is that the body size of mannequins used to advertise female fashion is unrealistic and would be considered medically unhealthy in humans. It is unclear why the male mannequins can be a “human” shape and size, whereas the female mannequins cannot.

Many of the phenomena of fashion are harmless, but the trend of extreme thinness is not without dangers. And it is not a British problem. In 2015, Inditex pulled “anorexic mannequins” after more that one hundred thousand signatures were collected in change.org to do that. Mannequins aren’t people, nor do they have a sign on them saying “you need to look like this”. But they are representations of the human body that are used to sell fashion and an idea of beauty. There is clear evidence showing that the ultrathin ideal is obnoxious and it is contributing to the development of mental health problems and eating disorders. There is no excuse for the continued use of emaciated mannequins (2). Anna Riera, who initiated the petition in change.org, declared “I know changing the mannequins is only a start, but I think it will help lots of people give the issue the recognition it truly deserves”.

References

- Rintala M, Mustajoki P (1992) Could mannequins menstruate? BMJ 305(6868): 1575-1576. ↩

- Robinson E (2017) Female mannequins aren’t just skinny, they’re emaciated. The Guardian. May 12. ↩

- Robinson E, Aveyard P (2017) Emaciated mannequins: a study of mannequin body size in high street fashion stores. J Eat Disord 5: 13. ↩