The ‘prehistory’ of philosophy of science (11): On ancient science and scientific progress, or Artemidorus’ dream

The ‘prehistory’ of philosophy of science (11): On ancient science and scientific progress, or Artemidorus’ dream

Just to take stock of what we have encountered in the previous entries of this series, regarding the ideas of contemporary philosophy of science than can find some kind of ‘ancestor’ in the works of ancient ‘philosophers’, we can mention Plato’s and Aristotle’s discussion about what are the essential differences and relationships between ‘scientific’ and other ‘lesser’ types of knowledge (like ‘opinion’ or ‘experience’), the former’s insights about the virtues of ‘theoretical unification’, as well as the latter’s analysis of the idea of ‘demonstration’ and of the different types of ‘causal explanation’ (including a rudimentary view of the notion of ‘supervenience’), and, going beyond the work of these two philosophical giants, we have also seen how the fundamental roles of empirical observation and careful logical reasoning (more than metaphysical speculation) were also established as the cornerstones of scientific research by the philosophers of the Hellenistic times. We also mentioned in the first entry of the series that there are stark differences not only between ancient and contemporary science, but on the philosophical understanding of the nature and structure of science: first, the institutional ‘entrenchment’ of science was very precarious in Greek and Roman times, as compared to how they become after the Scientific Revolution of the Modern Age, and especially after the State started to be its main patron in the 19th and 20th centuries, and hence most of science’s social aspects were basically out of sight for ancient philosophers (though not completely, as we shall see in a moment); and second, contemporary epistemologists are more aware than their ancient predecessors of the provisionality and mere probability of scientific knowledge, perhaps due to our having experienced the dethronement of many theories that once were considered the epitome of certain knowledge (but, as I shall comment, this difference is perhaps restricted to the philosophical interpretation of ‘knowledge’, and not a faithful description of the ancient ‘natural philosophers’ real attitude towards their attainments).

In this entry I am going to depart a little bit from what ‘philosophers’ (I mean, philosophers in their task of lucubrating about the ‘epistemological or metaphysical foundations’ of science) said about the topic, and will focus instead on the (‘philosophical’) view of ‘science’ held by ‘practicing scientists’ and ‘intellectuals’ widely understood had in the Ancient times. The many inverted commas in the preceding sentence are due to the fact that, by then, most of what is mentioned there was just named philosophy/philosopher/philosophical, and we have to attend mostly to what the relevant people did, in order to classify them more as ‘a scientist’ (the closer expression in the times would be physikos -or physicus, in Latin- what after all was just an abbreviation of ‘natural philosopher’) or as ‘an intellectual’ (i.e., somebody writing about these topics without pretending being in the task of providing us with anything close to a ‘philosophical grounding’ of knowledge, nature, or whatever). In conversations on this topic, the authors of the era often referred to those involved in that kind of ‘grounding’ as ‘theologians’, though we don’t have to bring to our mind the image of a priesty professor trying to give a patina of rationality to the religion he or she happens to profess, but rather someone like Plato (with all his other-worldly metaphysics) or even Epicurus (who also talked about the gods, though as blissful, eternal and dainty collections of atoms navigating the infinite space without worrying at all about human miseries). This rather reflects the common view in the Hellenistic and Roman era (though based on Platonic and Aristotelian ideas) that ‘theology’ was the ‘science’ of the first principles, and that ‘proper science’ (i.e., natural philosophy and mathematics, what Aristotle had called ‘second philosophy’) only came afterwards.

Hence, the fact is that, in the six centuries since Aristotle’s death till the climax of the Roman Empire before the almost mortal crisis of the mid-3rd century, it is when ancient science produced most of its greatest discoveries, and the people of the era were evidently conscious of the fact that ‘philosophy’ (‘theology’, ‘metaphysics’, or ‘first philosophy’) was clearly lagging behind ‘science’ in terms of its fertility. Philosophical schools still reigned supreme in the intellectual domain, and wealthy people still sent their sons (much less their daughters) to Athens in order to be educated by the stars of the Academy, the Lyceum, or the Stoa. But as for the question of which one of these ‘schools’ had the ‘Truth’, the common consensus was that something like a permanent stalemate had been achieved, and an eclectic mix and balance of thesis and arguments about metaphysical questions (like that exemplified by Cicero) had become the most ‘elegant’ position amongst the literate classes. Instead, the same Cicero, as well as nearly every other author of the time, like Pliny, Strabo or Seneca, just to name a few, explicitly admitted that ‘science’ (including mathematics and ‘natural philosophy’, as the knowledge of the causes and forms of natural phenomena, from astronomy to agriculture, from medicine to engineering) not only had progressed in the past, but was still progressing, even if some of their results were obviously ‘better’ than others. Seneca, for example, confided that ‘in the future’, empirical investigation would finally settle whether it is the sun what turns around the earth or vice versa, and even expected that, at some point, science would allow us to discover planets and star so faint that they are invisible to the naked eye. They also believed that this kind of progress was the most characteristic feature of ‘science’, and that this progress would spread towards all aspects of human life, making it better and more comfortable (cf. Carrier 2017).

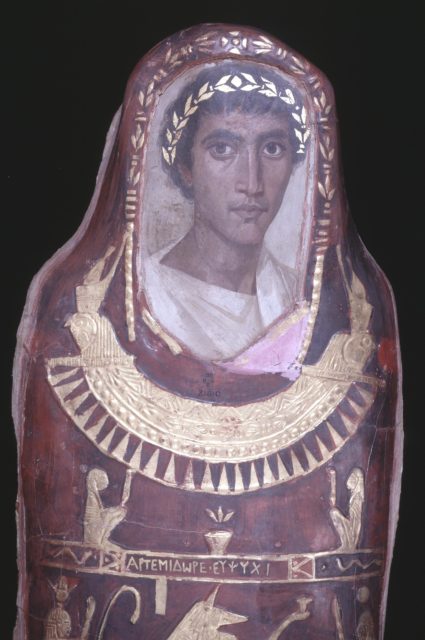

Surely, being this common-sense notion of ‘scientific progress’ more a ‘popular idea’ than a ‘philosophical concept’, the Ancients basically lacked a doctored view of what this kind of progress might consist in, in the sense of a sophisticated discussion about what were the logical relations between ‘successive theories’ (they even lacked the idea of ‘scientific theories’ as entities susceptible of ‘logical analysis’, beyond the nuances of a Chryssipus we saw in the last entry), a clear conceptual framework to understand the relations between ‘pure’ and ‘applied science’, or even a notion similar to that of Imre Lakatos’ ‘research programmes’ or Thomas Kuhn’s ‘paradigms’. But they, and in particular the ‘natural scientists’ (or physikoi) themselves, ended having a rather clear idea of how scientific progress can be attained. Perhaps Galen (2nd-3rd centuries AD), surely the most eminent medical scientist of the age, is the one that most clearly exemplified this, and his many ‘errors’ (mostly due to the impossibility, with the technics of the date, of understanding or manipulating anything in a living body that is so small that cannot directly be seen, like cells or biomolecules, or even capillaries) must not eclipse his astounding number of correct insights both in anatomy and in therapy. But I want to close this entry mentioning one much more obscure of Galen’s contemporaries: Artemidorus of Daldis (or ‘of Ephesus’, his real birthplace, though there were so many famous people from Ephesus, that he chose to be known after his mother’s city name).

Artemidorus attempted to establish a new science that were rationally grounded on the methods that had been proved to be successful in many other fields, from medicine to geography, from astronomy to zoology: systematic collection of experiences, without being tutored by metaphysical speculations or apriorist prejudices, whereas organised according to the most logical and rational arguments. As the bravest geographers and natural historians did, he travelled almost all the known world (from Rome to Levant, from Greece to North Africa) in order to gain knowledge from the experience of ordinary people and what we would call ‘village healers’, interviewing probably thousands of individuals, what, together with the reading of everything that had been written on the topic (what, by the way, he didn’t find very trustworthy), provided him with an impressive ‘database’ on which trying to build a logical system. His aim was no other than providing future ‘professionals’ with a guide that help them to make the best diagnoses and forecasts, bettering so the life of people as medicine and engineering had done and were doing. He wrote the most systematic book on the topic to date and for many centuries, perhaps not matched till the work of a well known author around 1900, though this was based on rather different hypotheses, of course. Artemidorus, however, though relatively more popular in the following centuries than most of the other scientific authors that had preceded him, was chronologically at the verge of the times of ancient science, and so he didn’t find successors of his ambition, cleverness and scientific talent, and hence his work became little more than a dream.

Sorry, I have forgotten to mention the topic of Artemidorus’ research, but you can easily infer it from the title of his book: Oneirocritica.

REFERENCES

Artemidorus, Oneirocritica (on the interpretation of dreams), Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2012.

Carrier, Richard, The scientist in the early Roman empire, Durham (N. Ca.), Pitchstone, 2017.

1 comment

[…] Zelan ulertzen zuten zientzia Erroma eta Greziako “zientifikoek”? Aurrerapen zientifikorik al zegoen haientzat? Jesús Zamoraren The ‘prehistory’ of philosophy of science (11): On ancient science and scientific progress, or A… […]