Growing inequalities in science

Growing inequalities in science

One of the most common misconceptions regarding inequality consists of thinking that an unequal distribution of resources is the result of an unequal effort to achieve them. Although this might be the case in certain situations, when it comes to particular individuals, the fact is that there are systemic structural forces governing the result of our efforts. The possibility of our personal, social or professional success still pretty much depends on our ascribed status, that is, an involuntary assigned position within the society. Sociologists use the expression social stratification to describe the way in which these structural forces organize groups and individuals in a phenomenon common to all societies.

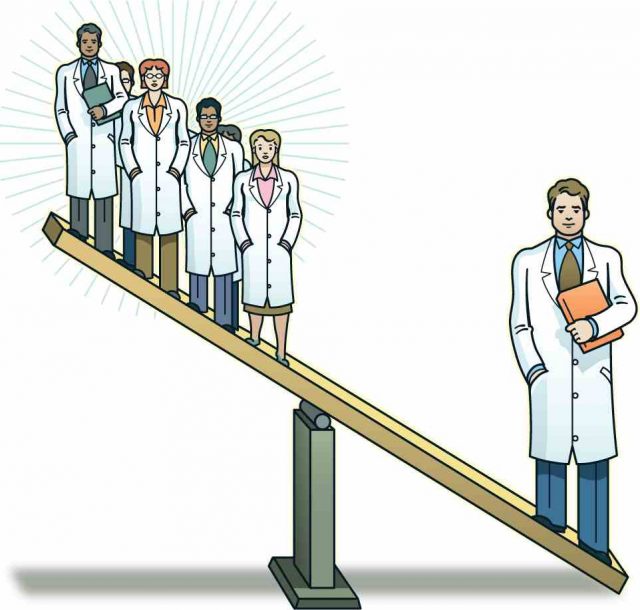

Inequality affects every human activity, including that of scientific research. The allocation of resources, rewards, prestigious grants and many other benefits both for individual scientists or scientific institutions are highly concentrated in a relatively few hands. Back in the 60’s, the English historian of science Derek Price considered this inequality in science as inherent, and called it ‘undemocracy’1. As a result, eminent scientists and scientific institutions are more likely to gain funds and recognition than lesser-known scientists and institutions for comparable contributions, leading to what the sociologist of science Robert Merton referred to as the “Matthew effect”, quoting the Bible: “For to all those who have, more will be given, and they will have an abundance; but from those who have nothing, even what they have will be taken away”2.

But, although this social stratification in science has always been present, it seems that in the last few decades globalization and Internet technologies have deepened the inherent inequality in science. This is the hypothesis put forward by Professor Xie, from the University of Michigan, who in a recent issue of Science analyses potential sources of inequality in scientific research3. According to the author, inequalities appear mainly in three domains: resources, research outcomes and rewards. Due to the Merton’s “Matthew effect”, eminent scientists and institutions accumulate publications, citations, research grants, funding, prestigious awards and visibility in the media, leading to a “winner-takes-all” system that subverts merit-based criteria.

Undoubtedly, Internet technologies have made it possible the rapid and broad diffusion of results as well as the creation of global collaborative networks, which in turns favor fairer competition. But it is also necessary to point out that, in a phenomenon very well known in other economic fields, successful institutions from developed countries tend to derive the more labor-intensive scientific work to less-developed countries due to the lower costs, intensifying inequality at an individual level. Even in the most developed countries, researchers have to put up with great job uncertainty. A recent PhD recipient is much more likely to expend years of postdoctoral fellowships and temporary employments than aiming for a regular academic position.

These concerns have been perfectly addressed in the editorial of the current issue of Science, Technology and Human Values by professor Edward J. Hackett, from the School of Human Evolution and Social Change at the Arizona State University, including these and many other important aspects of science stratification in what he has coined as ‘academic capitalism’4. Hackett begins his dissertation quoting sociologist Max Weber, who a century ago warned against science becoming a capitalist enterprise where researchers would strongly depend on the sources of capital, thus leading to scientists’ alienation, dissatisfaction and uncertainty.

Nowadays, this absolute pre-eminence of capital over every human activity is clearly shaping the landscape of scientific research too. Universities and other scientific institutions hardly compete for funds to construct and equip laboratories, support research and researchers and finally reach the top of the scientific ladder. Of course competition has its positive aspect as an incentive for coming up with important discoveries and technological advances, but the fact is that, at the end of the day, private capital addresses research agendas, allocating funds for topics with an immediate output in terms of economic performance rather than for those that deepen fundamental knowledge or enhance human well-being.

In a perfect vicious circle, the benefits of this research go back to the capital owners, increasing their influence on the future development of knowledge and innovation. In the meantime, relevant scientific work is being disregarded or just blocked. Hackett mentions humanities and social sciences as some of the most overlooked by capital, which clearly has an impact in terms of funds, resources and jobs available in these fields. Even relevant subjects in these areas are being relegated in educational programs.

At this point, Price’s term “undemocracy” becomes boldly significant. Professor Hackett includes a really meaningful quote from economist Thomas Piketty: “Extreme inequality makes it impossible to have proper working of democratic institutions”. University, as the institution for higher education and research par excellence, must be guided by democratic and humanistic values rather than strict capitalist criteria. Otherwise, as Weber claimed, old university constitution will become fictitious.

Both Professors Xie and Hackett strongly encourage scientific researchers to deepen in the subject of how capital influences research agendas and the growing inequalities abounding these days in the scientific landscape. More empirical work is needed in order to understand the mechanisms and effects of these phenomena, which will be essential to find the proper way to compensate them.

References

- D. J. Price, Little Science, Big Science, Columbia University Press, 1. New York, 1963. ↩

- R. K. Merton, The Matthew Effect in Science, Science, 159 (1968) 56-63. ↩

- Xie Y. (2014). “Undemocracy”: inequalities in science, Science, 344 (6186) 809-810. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1252743 ↩

- E. J. Hackett, Academic Capitalism, Science, Technology & Human Values, 39 (2014) 635-638. doi: 10.1177/0162243914540219 ↩

2 comments

[…] No es raro encontrar personas que piensan que la distribución de los recursos disponibles depende exclusivamente del nivel de esfuerzo que realizan los componentes del grupo en el que se distribuyen. Si bien puede que sea así para personas […]

[…] arabera. Zientzia ez da honetaz libro eta, dirudienez, txarrera doa. Silvia Románek kontatzen digu Growing inequalities in science […]