Neuronal fingerprints of premeditated violence

New York, Madrid, London, Susa, Dikwa, Kuwait, Paris, Ankara, among many others…, and now Brussels. A disturbingly long list of cities that have suffered the appalling hit of terrorist attacks in recent years. And while passing over the shock, we can hardly avoid asking ourselves about what are the causes of such destructive behaviours. Beyond socio-political factors, at the level of individual brains neuroscientists are getting every day closer to deciphering the neuronal roots of violence. In a paper1 published recently in Nature Neuroscience, researchers found new clues on how the bad intentions that usually precede violence originate in the brain. Scientists also found how to prevent aggression-seeking behaviour through interventions that blunted the activity of neurons in the hypothalamus.

The study showed how warning signs of premeditated violence link to a particular subdivision of the hypothalamus – a region in the brain that controls a range of primary motivations including hunger, sleep and sexual drive.

The same researchers had shown that activity in this brain locus is capable by itself of triggering violent behaviour. Now, they addressed if in a preparatory pre-attack stage the same region in the hypothalamus is also important. The aim was not to study the consummating motor behaviour in actual assaults but the underlying aggressive motivations.

Researchers designed a mouse study to observe aggressiveness independently from bullying behaviour. To do this, scientists watched mice before and during an aggressive social encounter. In the pre-encounter session, there was not any social cue that could signal or provoke a violent response. But mice could still proactively seek a future aggressive encounter, which happened only upon the mice performing a specific action. Only if a mouse poked its nose into a nose-poke infrared detector, then the mouse got access to a weaker mouse which they could then bully.

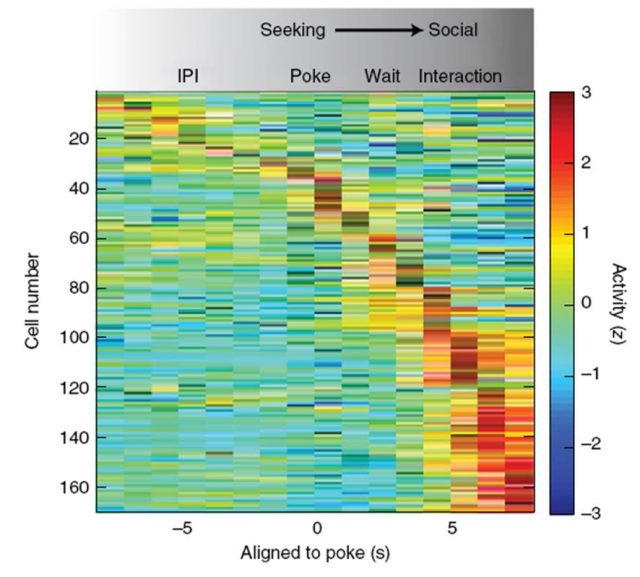

Researchers set recording electrodes in the hypothalamus of aggressive mice to explore how aggression and aggressiveness are encoded in individual neurons and in neuronal populations. Also, to prove causal relationships between neuronal activity and behaviour, researchers carried out independent experiments to stimulate and silence neurons and check their behavioural consequences.

First, researchers found that aggression-seeking behaviour by itself modulates the activity of neurons in the hypothalamic sub-region under study. While mice were in the pre-encounter session, several neurons in their hypothalamus changed their activity in a way that paralleled aggression-seeking behaviour. Some cells ramped up their firing reaching a peak later during the actual social encounter. But other neurons showed a different response: they fired only during the nose-poke, or they shut down just a few milliseconds before, or did not respond during nose-pokes but later during attacks. Neuronal responses thus reflected actual attack behaviour and aggressive premeditation in coherent but different manners.

As shown before, researchers were able to blunt mouse attacks by silencing neurons in this portion of the brain. Now also, researchers could weaken the earlier aggression-seeking behaviour as evidenced in a 50 % reduction of pre-violence nose-poking counts. In a final experiment, researchers obtained the opposite effect – mice performed quicker the violence-seeking nose-pokes and attacked later more intensely – by stimulating neurons in the same sub-region of the hypothalamus.

While these findings establish that neurons in distinct hypothalamus sites are crucial mediators of aggressive motivations, future studies will need to determine if these mechanisms are applicable to humans. “Our study pinpoints the brain circuits essential to the aggressive motivations that build up as animals prepare to attack,” said led author Dayu Lin in a press release of the NYU Langone Medical Center in New York (USA). “Targeting this part of the human brain with treatments meant to curb aggression remains only a distant possibility, even if related ethical and legal issues could be resolved,” pointed Lin. “That said, our results argue that the hypothalamus should be studied further as part of future efforts seeking to correct behaviours from bullying to sexual predation.”

References

- Falkner, A.L. et al (2016): Hypothalamic control of male aggression-seeking behavior. Nature Neuroscience. DOI: 10.1038/nn.4264 ↩

2 comments

[…] ¿Podrían encontrarse rastros en el encéfalo de una violencia premeditada? José Viosca en Neuronal fingerprints of premeditated violence. […]

[…] Seguir leyendo en Mapping Ignorance […]