The value of knowledge

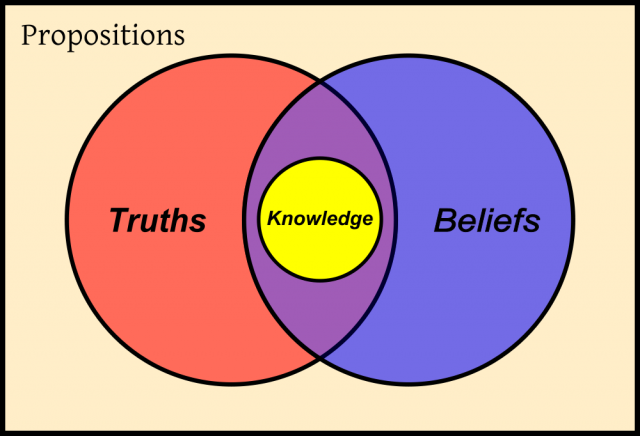

That knowledge is valuable is just a truism within our ‘knowledge driven economies’, but it is not that (economic) kind of value what I will talk about in connection to knowledge. I want to introduce, instead, a current and vivid debate in an arcane corner of philosophy. It is a debate about the nature of knowledge, a question that has been driven philosophers mad since the origin of their discipline. In two of his most famous dialogues (the Meno and the Theaetetus), Plato make Socrates interrogate his neighbours about what is to know something. One of the answer that the characters examine is that to know can be divided into three things: first, to know something (e.g., to know that Homer wrote the Iliad), one has to believe that Homer wrote it; second, that belief must be true; and third, one must have a justification for his or her belief, one must not happen to have that true belief by sheer luck, so to say (for example, if I, knowing nearly nothing about classical poetry, happen to think that ‘Iliad’ refers to the Aeneid, and ‘Homer’ refers to Virgil, I may happen to have a belief that I express as ‘Homer wrote the Iliad’ though what I’m really meaning is that Virgil wrote the Aeneid; in such a case, we wouldn’t say I know that Iliad was written by Homer). That knowledge is ‘justified true belief’ has been taken during almost two millennia and a half as probably the most obvious response to our question, in spite of Plato himself finally discarding that answer in favour of a more mystical (at least in the sense of being impossible to define) vision of real knowledge.

In recent years, some philosophers have tried to ruminate a little bit more deeply into the problem by considering whether the difference between ‘merely believing’ a truth and knowing it could consist in the latter being something more ‘valuable’ than the former, and if so, what kind of ‘value’ would be involved here (see Kvanvig 2003 1, Pritchard 20072). Most authors within this line of thinking have tended to conclude that knowledge must have some kind of ‘intrinsic’ value that merely true beliefs lack. For, after all, if the value of knowledge were merely instrumental (i.e., ‘extrinsic’, depending ultimately of the practical things we manage to get with its help), then truly believing (but lacking to really know) that this is the road to Seville is exactly as valuable as knowing it: in both cases I will take the right route if what I want to do is going to Seville. So, it seems that there must be something not related to the practical success of acting on the basis of my beliefs, and that makes of beliefs that happen to be also real knowledge more preferable than those that do not. But some philosophers (e.g., Sosa 20033) have argued that the only epistemic value deserving this name is truth (i.e., truth is the ultimate goal of our information-gathering activities), and by hypothesis, since we are comparing here items knowledge vs. true beliefs that fall short of being knowledge, both should have the same value. Other possible epistemic values considered in the literature are understanding, relevance, explanatoriness, but the problem is that all these things seem to depend on the content of the proposition that is known or believed, not on whether this proposition is known or ‘merely’ believed. So, it seems that the question is far from being resolved.

One recent argument against the very idea that knowledge is more valuable than ‘mere’ true belief has been offered by Steve Petersen (2013)4, who defends what he calls a ‘utilitarian epistemology’, i.e, one based on the principle of utilitarianism according to which the only thing which is truly valuable is welfare (or ‘happiness’, ‘pleasure’, etc.). utilitarianism is not only a respectable ethical theory, but also the default ethical position in economics and all research carried out within the frame of ‘rational choice theory’, in which agents act according to the maximisation of ‘utility functions’. Can it also be applied to the problem of the value of knowledge? The answer seems to lead us to what we said at the beginning we were not being talking about: the practical value of knowledge. According to this approach, epistemology would not consist in something like the study of the ‘nature’ of knowledge, but rather in the study of good ways of thinking: is it better to form beliefs by following such and such procedures, or by following these other methods? The question is whether ‘better’ should be understood as ‘leading to more welfare’ or as ‘leading to more truths’. Though Petersen argues that, in the end, the first answer is the only reasonable one, and that it is an empirical regularity that methods that are more reliable in the sense of producing a bigger set of true beliefs are also (and because of that) more efficient in bringing happiness to humankind, I am not totally persuaded of his arguments.

In the first place, though truth is perhaps no ‘ultimate’ value in the sense in which happiness or welfare are, it can be taken nevertheless as an intrinsic goal, in the sense in which we say that someone pursuits truth (or beauty, or stamps) ‘for its own sake’, and if it is truth what gives someone ‘welfare’ in this way (i.e, not merely because the practical use she can put those truths to afterwards, but for the sheer pleasure of knowing truths), there must be some ways or methods in which one needs to warrant that what has achieved is truth instead of other thing, methods that cannot only consist in ‘enhancing happiness in the end’ (for, in this case, our happiness is enhanced because of the methods being epistemically reliable, not the other way around, i.e., it is not that our methods are epistemically reliable because they enhance our happiness).

In the second place, our own cognitive system seems to work (fortunately, I would say) in such a way that whether we will be happier by knowing something or by falsely believing the opposite does not have in normal circumstances the ultimate saying on whether we end believing one thing or the opposite. Our cognitive system is, so to say, autonomous with respect to our values, interests, preferences or goals, not in the sense that it does not take into account what are the things that we value more strongly, but in the sense that it does not adjust what it makes us believe with the way we would prefer the truth is. Our innate cognitive mechanisms (and most of their culturally evolved applications) seem to work as if they were generally directed towards the truth (or at least, probable and relevant truth) independently on whether this truth makes us happier or more miserable, and this points again to the conclusion that epistemic evaluation can be made independently of utilitarian considerations.

References

- Kvanvig, J. (2003) The Value of Knowledge and the Pursuit of Understanding, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ↩

- Pritchard, D. H. (2007) “Recent Work on Epistemic Value”, American Philosophical Quarterly 44: 85–110. ↩

- Sosa, E. (2003). The place of truth in epistemology. In M. DePaul, & L. Zagzebski (Eds.), Intellectual virtue: Perspectives from ethics and epistemology (pp. 155–179). ↩

- Petersen, S., (2013), “Utilitarian Epistemology”, Synthese, 190:1173–1184. ↩