Epidemics and human behavior

Epidemics and human behavior

Think about yourself for a second: how did you react to the epidemic of the avian or the swine flu (H1N1) a couple of years ago? Did you go through special cares or measures in order to avoid the infection? Did you even really consider changing your everyday habits because of the fear and panic that these diseases caused in the population? These vital questions for people’s safety burst again into the public discussion when North America suffers one of the worst flu epidemics in recent years. Therefore, even if it may have reached a peak according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, there’s still a public health debate to be held about our risky behavior towards preventing the spread of infections. It would be desirable that the actions taken by the population in the case of an epidemic would follow what is established on a simple Government plan. But they aren’t.

Because here is where the main problem lies: according to a recent study, based on a multiplayer online computer game that simulates the spread of an infectious disease, the reason why a person is involved in a self-protective behavior, at the onset of an epidemic, is more likely to be correlated with his own infection history than with a rational decision based on the medical information available at the time. Furthermore, the researchers suggest, according to their results, that people’s willingness to engage in safe behavior waxes or wanes over time, depending on the severity of an epidemic: thus, people’s awareness at the beginning of the outburst may be high, inducing them to protect themselves, but, as the time passes, the percentage of the population who focus on their self-protection decreases if the prevalence is low.

The goal of this research1, done by a team of researchers, three economists and a computer scientist, at Wake Forest University, is to study human decisions in the context of a mass epidemic in orther to help in the development of new governmnet policies on infectious diseases. Moving forward from today’s control policies of epidemics, based on a single option choice (e. g., the vaccine as the only thing against the virus), to a more multiple and flexible menu relying on the heterogeneity in the behavior of the population (e. g., improve the preventive measures and also facilitate de access to medication).

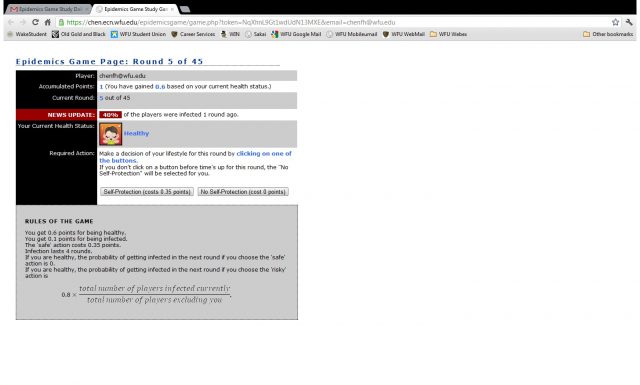

This virtual study consisted on simulating the spread of a infectious disease among the participants due to their own decisions and behavior over several of the game’s rounds (real weeks). At the beginning of each day in the game, players must choose between a risky-option or a safe one. If they select the second one, always at a cost, they will remain protected for one more round. Otherwise, they might get infected (the game has a default set up to the risky action if the player doesn’t select a healthy option in the duration of one round). Being protected in the game involves paying points and, at the end of the round, the player who is healthy without having spent them will get more than the one who decided to choose a healthy decision paying for it. It s a cost-benefit balance. Hence, when prevalence was high, players were more likely to spend points in self-protection.

The experiment was made twice: the first time, the cost for self protection was low and in the second game was high. The result of this showed that when protection was inexpensive it resulted on higher safety choices by the players. 51 participants managed to end the experiment, and they received, as a reward for completing all the study, a card for shopping via the internet which its value was equal to the number of points they have earned trough the game.

As a completely virtual experiment, this game has helped to achieve a big amount of data that could not have been obtained in any other way in the real world. Even if the creators acknowledge some minor flaws in their study, and they also pinpoint some other further expansion of their investigation protocol, above all, this experiment has managed to show how individual health decisions could be rational, but just in an economic sense.

References

- Chen F, Griffith A, Cottrell A, Wong Y-L (2013) Behavioral Responses to Epidemics in an Online Experiment: Using Virtual Diseases to Study Human Behavior. PLoS ONE 8(1): e52814. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0052814 ↩