Recognition of emotions by people with autism

Emotion recognition is the process of identifying human emotions. This is something that humans do automatically but computational methodologies have also been developed. Humans show universal consistency in recognizing emotions but also show a great deal of variability between individuals in their abilities. Whether persons with autism are able to recognize human emotions as well as normotypical individuals has been a major topic of study.

A study published by Candida C. Peterson and her group 1 has concluded that children with autism are just as good as children without autism at reading emotions as they are reflected in body language. This finding calls into question the earlier idea that children with ASDs have difficulty reading emotions, a prejudice that may have emerged from studies that only looked at whether children could read the emotions using the face or eyes as the only source of information. Most of the studies conducted so far to study the perception of emotions analyzed the identification of various emotional states using photos of faces or gazes, drawings of faces and, more rarely, videos or recordings of voices.

The results so far were contradictory: some studies on children with ASD had found deficits in perception and identification of emotions while similar studies, with the same measurements and similar samples, found no significant differences in relation to the results of normotypical peers. Various recent reviews on the subject coincided on one thing: that more than twenty years of research on the recognition of emotions by people with autism had not led to clear conclusions about a possible deficit.

The studies carried out so far also had various methodological problems. Many have focused on adults or young people, leaving the issue of the perception of emotions by children with autism especially unclear. Uljarevic and Hamilton 2 did a meta-analysis and of the 48 studies that met the established criteria to be included in their assessment, only 14 (29%) included children aged 12 or younger. A second problem, also noted in that same review, is that many studies had unacceptably small samples. Only 4 of the 14 studies that we have mentioned with samples of children; that is, 8% of the total, had samples of at least 15 people. The third problem is that the vast majority of the studies worked with only eyes or faces to show different emotions. In summary, it is possible that we are not analyzing whether children with ASD can distinguish emotions, but specifically whether they can distinguish them from the gaze or, at best, from the facial expression.

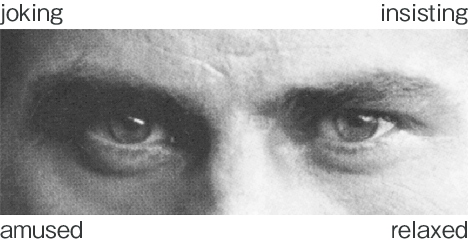

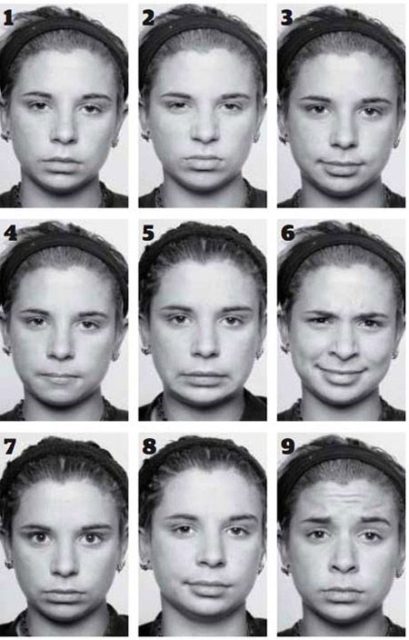

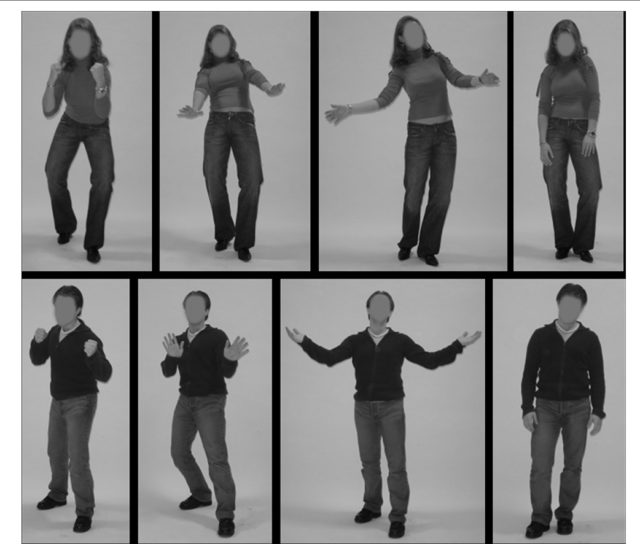

Peterson and her group have attempted to resolve this controversy by conducting two tests. In the first 34 children with ASD and 41 neurotypical controls, matched by age and verbal intelligence (verbal IQ), performed the so called Body-Emotion Test, a test developed by the research group. They also performed a widely used emotion recognition test using eye pictures as an initial element. This test is known as “Reading Mind in the Eyes: Child” or RMEC, it was proposed by Baron-Cohen and his group in 2001 and has been widely used. Peterson’s group also performed a well-validated battery of tests to analyze the theory of mind and a scale of empathy valued by the teacher. In the second study, 33 children with ASD and 31 neurotypical controls were analyzed using the RMEC test for the six basic human emotions; that is, a simplified version of that test.

The Body-Emotion test, proposed by the researchers of this team, consists of 12 items to assess the emotional language transmitted by the body. The new test follows a format similar to the RMEC but uses as stimulus photos of body postures where the face is unfocused instead of images of the eyes. To do this, they took two random photos of each basic emotion, enlarged them and blurred the facial characteristics of the person represented there. In each photo there were four possibilities printed on each corner. Only one was correct and the other three were, one, the emotion that according to a panel of three judges would be the most approximate description to the correct one and the other two were selected at random, attending to a final balance between positive and negative emotions. Finally, each child was asked how the person in the photo felt choosing one from the four corner options.

In the empathy test, the main teacher of the class scored the children on a prosocial subscale of the SDQ. The items describe generous actions of one child towards others (“is considerate of other people’s feelings”, “is kind to younger children”, etc.) and the teacher had to choose between three possibilities (“no”, “many times” or “true”).

The verbal intelligence quotient was measured with the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-Revised (PPVT-R), a standardized, normalized vocabulary test based on pointing responses to different images. It has a population mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15. Scores within a standard deviation of the mean are considered normotypical verbal intelligence.

The body language of emotions describes the non-verbal communication of emotions via the body posture, including the position of the body, the disposition of the arms in relation to the trunk, the gestures of the hand and the whole body, the movement patterns. In fact, powerful emotions completely transform the body posture instead of only affecting the face or the gaze. Examples of all acquaintances who have jumped into popular language are bodies “collapsed” by sadness, seized by fear or jumping for joy. A straight body with a compressed neck and advanced shoulders may suggest fear or hostility just as a relaxed body signals readiness for rapprochement or a contained or tranquil state.

When using tests based on the look or facial expression it is important to remember that many people with autism do not like to make eye contact, as this requires an encounter, proximity with the other person. However, reading body language can be done at quite a distance if you have that ability and the degree of social involvement is less.

Children with autism between the ages of 5 and 12 showed similar results to children without autism in the task of identifying six different emotions in photos of adults with blurred faces posing to show these emotions. In contrast, the normotypical children outperformed the TEA group both in theory of mind and in the standard and simplified versions of the RMEC test; that is, there were differences in these tests. The verbal IQ was not related to the perception of emotions either by body posture or by analyzing the look in any of the groups. However, recognizing the emotions of body posture correlated with the level of theory of mind, especially for children with ASD.

The main conclusions of the study are, with which we started this post, that children with autism are just as good as children without autism at reading emotions as they are reflected in body language. Second, that the perception of emotions through body language is clearly associated with understanding the theory of mind, especially for those children with ASD, but not with the quotient of verbal intelligence or empathy in behavior. Finally, reading emotions through body language rather than from the gaze was considered easier for both children with ASD and normotypical children.

References

- Peterson CC, Slaughter V, Brownell C (2015) Children with autism spectrum disorder are skilled at reading emotion body language. J Exp Child Psychol 139: 35-50. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2015.04.012. ↩

- Uljarevic M, Hamilton A (2013) Recognition of emotions in autism: A formal meta-analysis. J Autism Develop Dis 43: 1517–1526. ↩

2 comments

[…] jartzen dute arreta, aurpegieran edo gorputz osoan? José Ramón Alonsok ematen digu erantzuna Recognition of emotions by people with autism […]

[…] ¿Cómo reconocen las personas con autismo las emociones de los demás?¿Se fijan en los ojos, en la expresión de la cara o en el conjunto de cuerpo? José Ramón Alonso nos lo explica en Recognition of emotions by people […]