Emotional dampening of antidepressants

Serotonin or 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) is a neurotransmitter involved in various cognitive and affective functions. Drugs targeting serotonin transmission, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), are the first-line pharmacological treatments for many neuropsychiatric disorders such as major depressive disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder and anxiety. These antidepressants increase the concentration in the synaptic space of this neurotransmitter, although how that affects our mood is still unclear.

One of the criticisms to the side effects of these drugs is that they leave you emotionally flat, with a reduced ability to enjoy or feel. About half of the people who take an SSRI report noticing a decrease in emotions, both positive and negative. Depression is also often associated with a loss of pleasure in everyday activities, those little things that used to make you enjoy life.

Barbara Sahakian of the University of Cambridge and her colleagues have studied this flattening effect in 66 healthy people, who had not been diagnosed with depression or reported depressive symptoms 1. The volunteers were given either a tablet of escitalopram, an antidepressant from the SSRI group, or a placebo. The two groups were balanced for age, sex and IQ. After a minimum of three weeks of treatment, participants performed a series of tasks measuring the chronic effect of the SSRI on measures of “cold” cognition (including inhibition, cognitive flexibility, memory) and “hot cognition” including decision-making, critical judgment and, in particular, reinforcement learning.

At the end of the study, participants were asked whether they thought they had received escitalopram or placebo. In response, 53% of participants in the escitalopram group correctly guessed that they had received escitalopram, while 15.6% of participants in the placebo group believed they had received the drug.

The analysis confirmed that the two groups were well-matched and there were no significant differences in age, sex or intelligence quotient. Biochemical analysis confirmed that participants in the escitalopram group strictly adhered to the medication self-administration schedule, as evidenced by stable blood levels of escitalopram greater than 20 nmol/L. There were no significant group differences, after correction, between the placebo and escitalopram groups on any of the baseline questionnaires measuring their baseline cognitive ability.

One of the tasks looked at how volunteers learned with the use of rewards, reinforcement learning, in which participants had to choose between two stimuli. Through trial and error, they learned that one of the stimuli was more likely to generate a reward. Then, the odds of getting the reward suddenly changed from that stimulus to the other without warning to the participants, who had to discover and learn the new system.

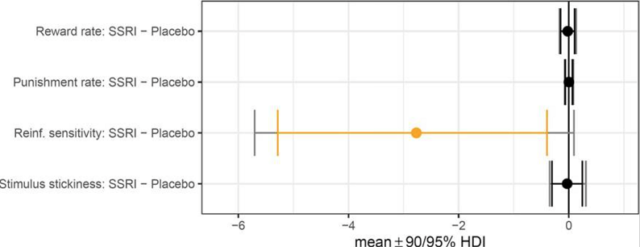

Those volunteers taking the antidepressant were 23% less sensitive to stimulus switching than those taking the placebo, a measure of how quickly they changed their stimulus selection. Other tests showed that taking the drug did not reduce their cognitive abilities. No other significant between-group differences in “cold” or “hot” cognition were detected. Escitalopram had no effect on “hot” cognition including emotional biases or moral judgments or on “cold” cognition including measures of attention, memory, cognitive flexibility and response inhibition.

These results suggest that SSRIs reduce people’s sensitivity to rewards or other pleasurable experiences. On the other hand, it is possible that the drugs also reduce the intensity of negative feelings, which may help depressed people. It is important that this study does not lead doctors to prescribe less antidepressants as they are important and necessary drugs for many sufferers of serious disorders, but perhaps this study can help doctors explain to their patients some possible side effects they may feel.

Among the limitations of the study 2 are i) it does not address whether the effect is similar in depressive patients, ii) SSRIs usually take between 4 and 8 weeks to block the serotonin transporter and produce a significant antidepressant effect. The time of the study (26 days on average) is clearly shorter with which the lower sensitivity observed could be fortuitous or disappear or worsen in the long term, iii) the sample size does not allow distinguishing sex-related differences, iv) the effect of escitalopram, highly specific, cannot be extrapolated to other SSRIs with a broader spectrum of activity, v) they do not really measure emotional blunting, which is a subjective experience, and vi) the number of questionnaires (17) and cognitive tests (12) that participants had to complete in one sitting was striking, and although equal for both groups, one wonders whether some effect of the drug might interact with the performance of the increasingly fatigued participants.

References

- Langley C, Armand S, Luo Q, Savulich G, Segerberg T, Søndergaard A, Pedersen EB, Svart N, Overgaard-Hansen O, Johansen A, Borgsted C, Cardinal RN, Robbins TW, Stenbæk DS, Knudsen GM, Sahakian BJ (2023) Chronic escitalopram in healthy volunteers has specific effects on reinforcement sensitivity: a double-blind, placebo-controlled semi-randomised study. Neuropsychopharmacology 48(4): 664-670 doi: 10.1038/s41386-022-01523-x . ↩

- Brincat C (2023) Why might antidepressants dampen our emotions? Medical News Today ↩