The surprising memory of Stokes-shifted photons

The surprising memory of Stokes-shifted photons

In recent decades, researchers have developed advanced techniques to detect and manipulate individual photons. A particularly intriguing field examines how nanoscale light emitters, resembling artificial atoms, produce these photons. In this vein, a new study 1 addresses a subtle question: when two such emitters release photons that are red-shifted due to energy loss, do these photons retain the quantum correlations that linked the emitters? Remarkably, the findings indicate that they do.

Stokes-shifted photons

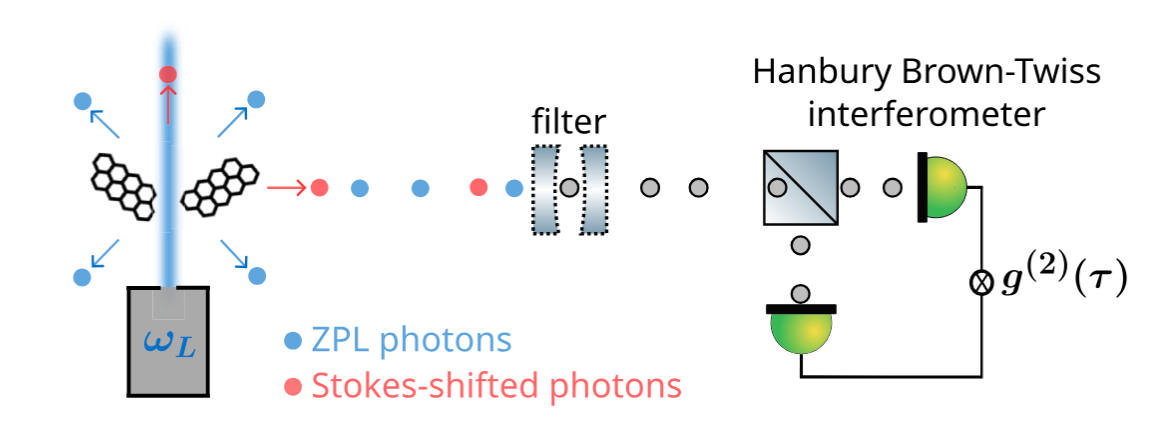

This work centers on experiments with two organic molecules, chilled down to super-cold temperatures to keep things under control. A laser hits them just right—not too hard, but enough to get them excited. When a molecule soaks up a photon from the laser, it jumps up to a higher energy level, like climbing a step on a ladder. Pretty soon, it drops back down and releases a photon of its own. If everything goes smoothly and it lands right back where it started, the outgoing photon matches the laser’s color exactly. But these molecules aren’t perfect; they wiggle and vibrate inside. Sometimes, when the photon escapes, it leaves behind some of that energy in the molecule’s vibrations. To make up for it, the photon comes out a bit redder than expected. Scientists call these redder ones Stokes-shifted photons, named after the physicist who first noticed this kind of energy shift in light.

You might think these shifted photons would be kind of chaotic and not very useful for probing deep quantum stuff. After all, they’ve dumped energy into those internal shakes, which could scramble the precise quantum details from the original laser absorption. Some researchers figured that if you only looked at these red-shifted photons, you’d miss out on that spooky, non-everyday connection where particles act in sync known as quantum coherence. But this study, through careful experiments and a fresh theoretical model, flips that idea on its head.

Timing is key

A big part of how they figured this out is by watching the timing of when photon pairs show up at detectors. If photons tend to arrive in clusters or spread out in patterns, that reveals clues about their origins. In this setup, the two molecules are pumped by the same laser, so their light emissions can sync up in surprising ways, almost like two dancers moving together without rehearsing, guided by some underlying rule. The key finding? Even when you filter everything to only catch those red-shifted photons, the timing patterns still show signs of that quantum connection between the molecules. The vibrations don’t erase it as much as people thought.

What’s more, the patterns for these red photons aren’t the same as for the unshifted ones. It all hinges on how the molecules share energy when they’re jazzed up by the laser. Sometimes they team up in a “bright” state, where they release light quickly and efficiently. Other times, they slip into a “dark” state, slowing things down. These group behaviors affect when photons pop out, and the study shows that the red-shifted ones keep clear marks of whichever state the pair is in. So, these photons remember the teamwork happening between the molecules.

A limitation in tech

The theory also predicts something delicate: a super-sharp spike in the timing pattern when two photons hit the detector almost at the exact same instant. This comes from interference between the light waves from each molecule. The spike is so narrow that most detectors can’t catch it clearly; they blur it out, leading to measurements that seem off from basic predictions. But the model’s smart enough to explain this as just a tech limitation, not a flaw in the physics itself.

Coherent calculations

The big takeaway is that focusing only on these energy-losing, red-shifted photons doesn’t cut you off from quantum coherence. These photons, even with their slight dip in energy, still whisper secrets about how the molecules dance with each other and the laser. Skip that coherence in your calculations, and your predictions go wrong; include it, and everything lines up with what the experiments show.

This is huge for tech that’s coming down the pike, like secure quantum communication networks, super-sensitive sensors, or gadgets that crank out perfectly timed photons when you need them. It also sharpens our view of quantum behavior in real-world materials, where vibrations and flaws are part of the package. Instead of wrecking quantum effects, these quirks can live alongside them, offering new insights.

In the end, this research paints Stokes-shifted photons not as flawed leftovers, but as clever carriers of quantum tales.

Author: César Tomé López is a science writer and the editor of Mapping Ignorance

Disclaimer: Parts of this article may have been copied verbatim or almost verbatim from the referenced research paper/s.

References

- A. Juan-Delgado, J. -B. Trebbia, R. Esteban, Q. Deplano, P. Tamarat, R. Avriller, B. Lounis, and J. Aizpurua (2025) Addressing the correlation of Stokes-shifted photons emitted from two quantum emitters Phys. Rev. Lett. doi: 10.1103/1z52-p73t ↩