Chronic wasting disease in Europe

Prion diseases are a group of severe conditions that affect the nervous system of many animals, including humans. Although their causes were highly controversial, there is a widespread agreement nowadays that they are originated and transmitted by prions, infectious agents with a normal and an abnormal structure. The abnormal prion protein infects the host animal by promoting conversion of normal cellular prion proteins to the abnormal form. The build-up of this altered protein is associated with widespread neurodegeneration that results in dramatic behavior changes and death.

Among the human prion diseases are kuru, Creutzfeld-Jakob disease, Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker syndrome and fatal familial insomnia. Among the non-human animal diseases are scrapie, transmissible mink encephalopathy, feline spongiform encephalopathy, exotic ungulate encephalopathy, bovine spongiform encephalopathy –commonly known as mad cow disease– and chronic wasting disease.

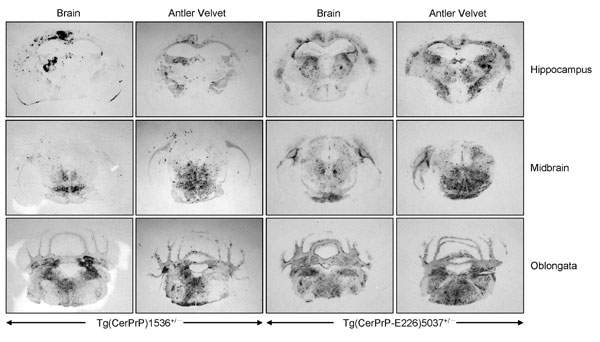

Chronic wasting disease (CWD) is a transmissible spongiform encephalopathy that has been hitherto only detected in North America and South Korea. The first case was identified in 1967 in a mule deer in a wildlife research facility in Colorado, USA. In 1976, it was identified as a transmissible spongiform encephalopathy. Later it was observed that it has spread to free-ranging and captive populations of cervids in 23 US states and two Canadian provinces. The disease spread to South Korea when a shipment of live elk carrying presumably the infection was brought into the country for farming in the late 1990s. In 2006, a first chronic wasting disease surveillance was carried out in roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) in the northern part of Belgium. It was the first preliminary active epidemic surveillance of European wild cervids in Europe, in order to improve the knowledge of the CWD status in free-ranging deers. Spleen samples (n=206) and brain samples (n=222) of roe deer were examined for chronic wasting disease using the antigen-capture enzyme-linked immunoassay and immunohistochemistry. There were no indications on the occurrence of TSE in any of the samples1. This April, unfortunately, CWD has been detected in Europe for the first time 2.

The animal was a free-ranging wild female reindeer (Rangifer tarandus tarandus) from the Nordfjella population located in the alpine regions of southern Norway. It was detected in the middle of March 2016 in connection with a capture program for GPS-collaring using helicopter performed by the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research. The animal was sick and the body condition was below medium, but it has still some adipose tissue. It died and the carcass was sent to the Norwegian Veterinary Institute in Oslo for necropsy. The postmortem analysis demonstrated the presence of prions both by the first routine test (ELISA) and in two supplementary analyses (Western blotting and immunohistochemistry) (3). It is the first time that CWD is detected in Europe, and the first time it is detected in this species since previously it was thought to be restricted to mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus), white-tailed deer (O. virginianus), elk (Cervus elaphus nelsoni) and moose (Alces alces shirashi).

The development of the disease is slow as in other prion diseases and affected cervids show loss of body condition and altered behavior. There is no cure or vaccine and as far as we know, CWD is always fatal. Initial experimental research suggests that human susceptibility to CWD is low and there may be a robust species barrier preventing CWD transmission to humans 3. Norway has put in place additional surveillance.

It is unknown how the disease has appeared in Europe. It seems unlikely that it was imported as in the Korean case since there are no records indicating transport of cervids from North America to North Europe. It might have arisen spontaneously or jumped the species barrier from another transmissible spongiform encephalopathy caused by prions in sheep called scrapie. A large number of free-ranging populations of reindeer graze in areas where scrapie has been detected; however, this jump has never been detected before.

It is widely accepted that feeding the cattle, which are normally herbivores, with the remains of other cattle in the form of meat and bone meal, caused the bovine spongiform encephalopathy, probably from the contamination of the meal from sheep with scrapie that was processed in the same slaughterhouse. Bovine spongiform encephalopathy was transmitted to human beings –causing the new variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease– by eating food contaminated with the brain, spinal cord or digestive tract of infected carcasses. However, the infectious agent, although most highly concentrated in nervous tissue, can be found in virtually all tissues throughout the body, including blood. Nevertheless, it is a mystery how it has affected a wild animal.

The CWD-infected animal belongs to the last remaining wild tundra reindeer in Europe. Hunting of wild reindeer and herding of semi-domesticated reindeer (for meat, hides, antlers, milk and transportation) are important to several Arctic and Subarctic peoples, including the Saami, Nenets, Khants, Evenks, Yukaghirs, Chukchi, and Koryaks in Eurasia, and there is an unbroken tradition of reindeer hunting from post-glacial Stone Age until today. Thus, and epidemic can be a hard blow for these human populations, not taking into account possible effects of quarantines in Christmas season since flying reindeer are said to pull Santa Claus’s sleigh.

References

- De Bosschere H, Saegerman C, Neukermans A, Berkvens D, Casaer J, Vanopdenbosch E, Roels S (2006) First chronic wasting disease (CWD) surveillance of roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) in the northern part of Belgium. Vet Q 28(2): 55-60. ↩

- Becker R (2016) Deadly animal prion disease appears in Europe. Nature ↩

- Kurt TD, Sigurdson CJ (2016) Cross-species transmission of CWD prions. Prion 10(1): 83-91. ↩