Copyright protection and the number of intellectual works

Copyright protection and the number of intellectual works

When analyzing the economic consequences of copyright protection one must consider first how it affects the number and quality of the works that it protects; second, which are the effects on the availability of these works, and third, how are the benefits and costs shared by the different agents of the market (consumers, authors, producers, etc.). In this article I will focus on the evidence regarding the effect of copyright protection on the number of intellectual works created.

The conventional argument to support copyright protection states that it encourages the creation of intellectual works as the author can see the benefits from the sale of the copies of his or her work. Diffusion is restricted to copies made by the copyright holder, whose monopolistic power is seen as a price to pay to have the intellectual work created in the first place.

This conventional thought has its theoretical counterpart in the Economic Analysis. The problem is that one can also write a theoretical model to reject the need of copyright altogether because the benefit of being the original and first and the exposure of one’s work makes enough incentive to create. Even further, one can write a model where granting a monopoly discourages creation as there may be many intellectual works that may use previous material that, under copyright provisions, is not easily available.

In other words, both possibilities are compatible with standard economic analysis without any resort to strange ad hoc hypotheses. The implication is that we cannot have much idea, not even an educated, provisional, a priori idea about the issue unless we resort to the empirical evidence. I will briefly review the kind of evidence, both theoretical and empirical, that made Economics question its initial ideas on the rationality of copyright provisions. The shift is taking place during the last years, and it is still difficult to foresee where it will lead.

As early as 1934, Arnold Plant 1 noticed that during the 19th century in the USA one could legally copy books written by British authors and that, yet, their publishers in the USA made enough profits to pay them good revenues. However, no serious empirical studies were collected for most of the following years, and only anecdotal evidence was presented to defend or criticize the copyright system. As recently as in the 80’s most works were theoretical models that favored copyright provisions. For instance, Novos and Waldman (1984) 2 developed a model in which it is theoretically possible for an increase in copyright protection to increase social welfare by encouraging more production without paying a welfare loss due to underutilization. Another example is Johnson (1985) 3, who develops two different models to make a case for restricting copying because of the new copying technologies under extensive use in the 80’s.

Around the same time (and in the same journal), a serious empirical work was published that contradicted the theoretical view, at least partially. Liebowitz (1985) 4 addressed the question for the copying of scientific journals and found that publishers can indirectly appropriate revenues from users who do not directly purchase journals and that photocopying has not harmed journal publishers. Greater exposure of the publication via copying was enough to compensate the publishers. They conduct three different tests that in the end show that the journals with more citations and more intensive use in the libraries were able to charge a higher institutional price, and that citations and use only increase with copying. Also, the exposure effect was related with an increase on personal subscription (even if individuals could make cheap copies of the journals without the need to subscribe.) Moreover, the period of growth in reprography has not coincided with a decline in for journals. Rather, the opposite is true.

This and other empirical observations encouraged some authors to write models to explain the possibility of intellectual creation without the need of the monopolistic power granted by the copyright or the patent systems. To have a sound theoretical model to show that there exist sources of rents in the absence of intellectual property rights one has to wait until the works by Boldrin and Levine (2002, 2005, 2008) 5, 6, 7. The key to these models is the careful consideration of the dynamic structure of the economic problem, where copying takes time, and can only be made profitable after a delay so that the owner of the original work can sell it for a profit. In a later work, Henry and Ponce (2011) 8 show that the delay does not need to be a pure technological issue, as it may be a consequence of the strategic behavior of imitators: they wait for the original inventor to sell a contract (which discloses all the information needed to reproduce the work) and, thus, produce a competitive market for the idea where the price of resale is lower (their model is more appropriate to patents than to copyright, but the idea is of interest to all intellectual creation).

But let’s go back to the empirical evidence. Landes and Posner (2003) 9 provide a strong piece of evidence that the expected value of copyright protection is very low. The reason is given by the fact that, although the fee to register a work is very low in the USA (around $20), small increases in the fee resulted in a sizable reduction in registrations. This can only be explained if authors see a very little advantage to get their works registered.

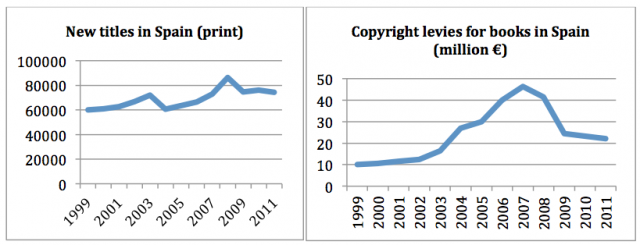

Ku et al. (2006) 10 use statistical analysis to test the old theory that increasing copyright protection also increases the number of works. They consider books, performing arts, motion pictures and sound recordings, and use the number of copyright registrations in the USA form 1870 until 2006 as an approximation for the number of works produced. Correcting for population, economy and technology they find that there is no consistent relation between law changes and registration. The authors summarize their findings in the following paragraph:

“The data indicates that one cannot reliably predict ex ante whether a law change will have a positive or negative relationship with the number of new works produced. In many instances, the same law change is associated with an increase in registrations in one category and a decrease in another without any substantive reason for the different outcomes. Moreover, our data suggests that laws increasing copyright protection AND reducing copyright protection are both likely to be positively associated with changes in the number of new works registered.”

The discussion about private copying and the extension or reduction of copyright provisions may be very passionate. However, researchers have been able to accumulate some empirical data that can structure the social and political debate. One argument that is often heard for increasing copyright protection is to guarantee the production of intellectual works. This argument, as we see, has no empirical validation. Researchers recognize the limitations of the empirical literature, which indeed needs to accumulate more data, and also needs to study the consequences of the new technologies. The evidence against the hypothesis may be scarce, but the evidence in favor, as far as we see in the academic research, is nil.

References

- Plant, Arnold, 1934. The Economic Aspects of Copyright in Books. Economica, 1(2), 167-195. ↩

- Novos, Ian E. and Michael Waldman, 1984. The Effects of Increased Copyright Protection: An Analytic Approach. Journal of Political Economy92(2), 236-246. ↩

- Johnson, William R. 1985. The Economics of Copying. Journal of Political Economy93(1), 158-174. ↩

- Liebowitz, S. J. 1985. Copying and Indirect Appropriability: Photocopying of Journals. Journal of Political Economy 93(5), 945-957. ↩

- Boldrin, Michele, and David Levine. 2002. The Case against Intellectual Property. American Economic Review Papers and Proc. 92(2), 209–12. ↩

- Boldrin, Michele, and David Levine. 2005. Intellectual Property and the Efficient Allocation of Surplus from Creation. Review of Economic Research on Copyright Issues 2(1), 45–67. ↩

- Boldrin, Michele, and David Levine. 2008. Perfectly Competitive Innovation. Journal of Monetary Economics 55(3), 435–53. ↩

- Henry, Emeric, and Carlos J. Ponce, 2011. Waiting to Imitate: On the Dynamic Pricing of Knowledge. Journal of Political Economy 119(5), 959-981. ↩

- Landes, William M., and Richard A. Posner. 2003. The Economic Structure of Intellectual Property Law, Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2003. ↩

- Ku, Raymond Shih Ray, Sun, Jiayang and Fan, Yiying. 2009. Does Copyright Law Promote Creativity? An Empirical Analysis of Copyright Bounty. Vanderbilt Law Review63. Case Legal Studies Research Paper No. 09-20. ↩