When “Eskimo” and “Inuit” are not the same thing: looking inside words

When “Eskimo” and “Inuit” are not the same thing: looking inside words

The usage of the words “Eskimo” and “Inuit” is one of these cases in which, all of a sudden, we are told we have been saying something wrong all along. Lawrence Kaplan from the Alaska Native Language Centre at the University of Alaska Fairbanks explained that the words “Eskimo” and “Inuit” do not mean the same1. Both names refer to the indigenous people of the Northern circumpolar region – which embraces parts of Alaska in the US, Siberia in Russia, Canada, and Greenland. Now: in some contexts, the word “Eskimo” may not be specific enough, as it refers to different groups of people of this region of the world such as the “Inuit” and the “Yupik”. On top of the misnomer, “Eskimo” has been considered a derogatory term as it was thought to mean “eater of raw meat” while “Inuit” translates to “the people”. The latter being a more acceptable term.

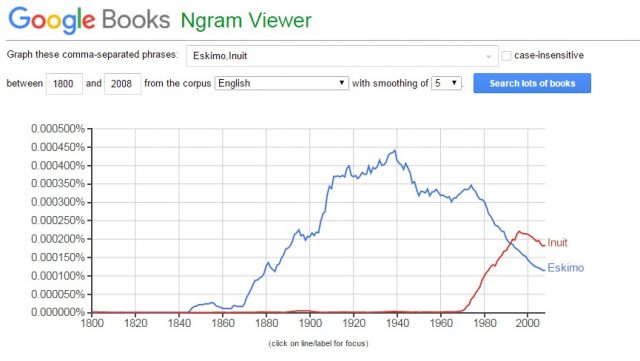

Possibly influenced by some of these sociolinguistic issues, the two words have suffered notorious changes in use over time, which are worth reviewing. To exemplify this, we asked Google to calculate the frequency of appearance of the words “Eskimo” and “Inuit” in English books. “Eskimo” was commonly used up until the 1990’s, the moment in which the word “Inuit” became more common. To some of us, this was probably sometime back in the 90’s, or even in the 2000’s. Time in which we were told or read somewhere that these two words did not exactly mean the same, and that we had to be wary about the way we used them. If we look at the frequencies of usage today, it seems that we learned our lesson, as the word “Inuit” is more often used than “Eskimo”.

Other than to explain changes in use, another question we can ask is whether the frequency of words such as “Eskimo” and “Inuit” – or other variables that may reflect how we perceive these words – may be useful to assess cognitive processes and, consequently, in other fields of linguistics, such as psycholinguistics or clinical linguistics. The answer to this question is affirmative.

In 1965, Oldfield and Wingfield 2 showed black-and-white drawings of objects to 12 adults and asked them to name what the object was (e.g., for a picture of a chair, participants had to say “chair”). These authors found a correlation between reaction times during picture naming and frequency ratings. That is, people took longer to say the name of a word, when the word was less commonly used and vice versa. This article has been since then cited for over 700 times! Having said that, the reason for which this may be the case is still somewhat controversial 3. Despite that, one of the relevant bits of this finding is that there are people with brain damage (due to stroke or dementia) that may have greater difficulties at producing less frequent words as compared to words that occur very frequently. Therefore, and regardless of the origin of these difficulties, assessment materials for people with language difficulties may be built by taking into consideration the frequency of words, as there may be people with brain damage that may have greater difficulties at saying words that are less frequent as compared to those that are more frequent 4. Indeed, if we would only use words that are highly frequent, we could miss out on correctly assessing language difficulties.

Another difference between “Eskimo” and “Inuit” can be looked at by considering psycholinguistic variables that reflect experiences that speakers of the language have with the words. In 1973, for example, Carroll and White 5 asked 50 adults aged 18-50 years to indicate on an 8-point scale when did they think they had learned different words (i.e., pre-nursery school period, nursery, kindergarten, first grade … up to ninth grade). This variable was named “Age of Acquisition”. Similarly to the frequency findings of Oldfield and Wingfield [2], Caroll and White found that “objects whose names were learned early were named faster [than those whose names were learned later in life]”.

Today, the age of acquisition of words can be used to predict how difficult it may be for people to process words, for example when naming a picture or to look for correspondences between similar words. More specifically, words that are learned later in life (e.g., quinoa, wholemeal) may be more difficult to process, as compared to words that were learned earlier in life (e.g., milk, sweet). From a clinical perspective, knowing the age of acquisition of words may be relevant to diagnose language disturbances in children who may not have acquired a certain number of words at a specific age. For example, it is generally accepted that English-speaking children learn and, therefore, use nouns early, while it is only when using multiword utterances that function words such as the determiner “the” or the pronouns such as “he” or “she”, may be used 6.

How about the examples “Eskimo” and “Inuit”? Do people think that they learned them at a similar age? To answer this question, it is possible to look at the work by Victor Kupermann and colleagues 7. These scholars used web-based crowdsourcing technology to obtained Age-of-acquisition ratings of 50 thousand English words. They indicated that the word “Eskimo” was on average learned at age 7. Their data also indicates that the word “Eskimo” is learned at a similar age than “vinegar”, “xylophone”, and “lighter”, almost 10 years earlier than other words such as “epidemiology”, “jurisprudence”, and “fauvism”, and 5 years later than words such as “mom”, “water”, and “spoon”. Unfortunately, these authors did not present data for the word “Inuit”. However and if the sociolinguistic and frequency data holds true, it may be possible to assume that most of us learned the word “Inuit” later in life than the word “Eskimo”. Therefore, provided that these two words were used in a language assessment test, we could predict that, when having to name these two pictures some people would have more difficulty at naming “Inuit” as compared to “Eskimo”. At the same time, the fact that the word “Inuit” may be currently seen as being preferable or more specific than “Eskimo”, could also imply that younger generations may be learning “Inuit” earlier in life than older people did.

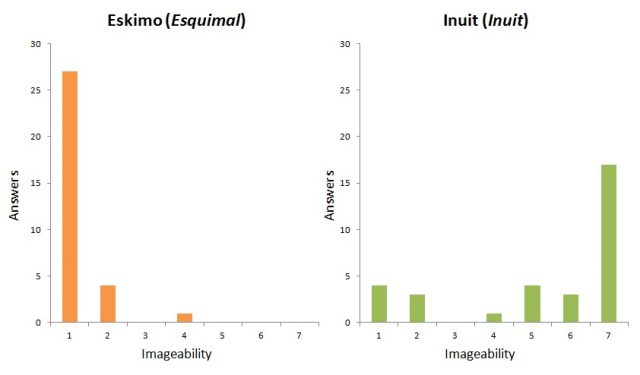

Another psycholinguistic variable that is relevant to have a look at is “Imageability”. This variable is used to indicate “how easily may speakers of a language be able to think of a mental image of the word”. In 1968, Paivio and colleagues asked speakers to estimate the imageability of a series of words. The authors indicated that words such as “anger” had a low rate of imageability while words that were more concrete such as “elephant” had a higher grade of imageability. From a clinical perspective, better performance on items that have high-imageability than low-imageability is frequent in people with language deficits 8.

Now do the words “Eskimo” and “Inuit” have a different imageability? To answer this question we used data from a bigger study that we conducted in collaboration with Anna Gavarró from the Autonomous University of Barcelona. In such study, 32 Catalan-speakers aged between 18-31 years were asked to indicate on a 7-point scale how imageable were a series of words (1 = very easy to imagine; 7 = very difficult to imagine), including the Catalan words for “Eskimo” (Esquimal) and “Inuit” (Inuit). The results of this study, which included many other words, indicated that 27 of 32 people thought that the word “Eskimo” was very easy to imagine, 4 people quite easy to imagine, and 1 person not easy or difficult. Surprisingly, and somewhat in contrast with the former results, we found a different pattern for the word “Inuit”. Only 4 of 32 people indicated that it was very easy to imagine, 3 people quite easy, 1 person not easy or difficult, and the other 24 people indicated that it was difficult to imagine (4 people difficult, 3 quite difficult, and 17 very difficult).

When contrasting the average sum of scores for these two words (“Eskimo” was 5.6 with a standard deviation of 9.9, and “Inuit” 24.4 with a standard deviation of 42.4) with the median value for all of the items that we considered in the experiment (10.1), we concluded that the word “Eskimo” was thought to be easy to imagine relative to the rest of the words in the experiment, while the word “Inuit” was thought to be very difficult to imagine. This information is in line with the fact that “Inuit” is a word that most of the speakers was probably learned later on in life. Interestingly, this data may also be telling us that the frequency of usage of the word, may not affect its imageability as much as it does age of acquisition. Having said that, this is only food for thought, as in this example we did not take into consideration potential differences in the age of the speakers when comparing English and Catalan data.

To sum up, in this article we showed how words may differ in aspects that go beyond their meaning, such as their frequency of use and the way we perceive them (e.g., when did we think we learned them, and how easy we think we can imagine them). We used these differences to introduce sociolinguistic and psycholinguistic aspects of the words “Eskimo” and “Inuit” that may be intrinsically interesting for the logophile. Furthermore, we showed how some of these differences are currently used to study the acquisition of language and to assess language impairment in brain-damaged populations. There exist many other variables that could be used to look inside words such as “Eskimo” and “Inuit”. Further work will allow researchers and clinicians to disentangle which of these variables are particularly indicative of damage in language processes and how these can be used to learn about mind and brain relations.

References

- Kaplan, L. Inuit or Eskimo: Which Name to use? Alaska Native Language Center. ↩

- Oldfield, R. C., & Wingfield, A. (1965). Response latencies in naming objects. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology,17(4), 273-281. ↩

- Whitworth, A., Webster, J., & Howard, D. (2014). A cognitive neuropsychological approach to assessment and intervention in aphasia: A clinician’s guide. Psychology Press: Hove. ↩

- Rofes, A., de Aguiar, V., & Miceli, G. (2015). A minimal standardization setting for language mapping tests: an Italian example. Neurological Sciences, 36(7), 1113-9. DOI:10. 1007/ s10072-015-2192-3 ↩

- Carroll, J. B., & White, M. N. (1973). Word frequency and age of acquisition as determiners of picture-naming latency. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 25(1), 85-95. ↩

- Bird, H., Franklin, S., & Howard, D. (2001). Age of acquisition and imageability ratings for a large set of words, including verbs and function words. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 33(1), 73-79. ↩

- Kuperman, V., Stadthagen-Gonzalez, H., & Brysbaert, M. (2012). Age-of-acquisition ratings for 30,000 English words. Behavior Research Methods,44(4), 978-990. ↩

- Paivio, A., Yuille, J. C., & Madigan, S. A. (1968). Concreteness, imagery, and meaningfulness values for 925 nouns. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 76(1), 1-25. ↩

6 comments

[…] Ocurre en algunas ocasiones que empleamos palabras distintas para referirnos a una misma realidad como si fuesen sinónimas. Y nada más lejos de la realidad. Adrià Rofes en When “Eskimo” and “Inuit” are not the same thing: looking inside […]

[…] de destaque: Mapping Ignorance var quads_screen_width = document.body.clientWidth; if ( quads_screen_width >= 1140 ) { /* […]

[…] Imagem de destaque: Mapping Ignorance […]

I was comparing methods of child rearing of the Eskimos, Inuit people, as well as other peoples including my own, the Jewish parents.

I very much am NOT on board with using Inuit to address all the northern peoples. This is tantamount to calling all White people ‘Americans’ the Yupik and Aleut people are just as relevant, though lower in populations, and don’t deserve to be PC washed with a blanket term that referrers to an entirely different group of people.

GOOD