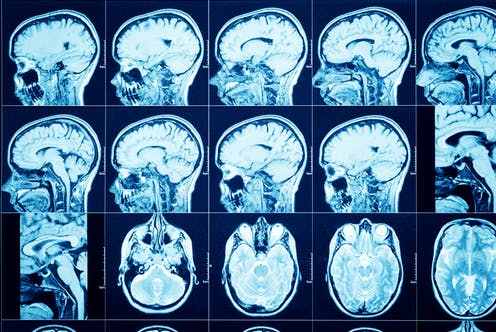

Coronavirus in the brain

To date, more than 50 million people have been infected with the new coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, and more than 1,2 million have died. It is a global problem, affecting everyone, but we are still learning how it infects, how it behaves, what causes harm to humans.

The virus is spread by the droplets produced by an infected person talking or breathing. By inhaling that air, the virus enters another person’s body and grabs receptors on the cells. An important point is that these receptors, the receptors for “angiotensin converting enzyme” ACE2, are not only in the cells of the respiratory system but also in other cell types such as neurons and glial cells. This makes the brain cells potentially targets of the virus and therefore vulnerable to SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Most people who become infected with the coronavirus have no or very mild symptoms, but there is one part that shows a serious evolution. It usually starts out as something like the flu, but then they develop a pneumonia that leaves them struggling to breathe. The usual image is that it is a virus that attacks the respiratory tract, those whitish lung X-rays for pneumonia, but these other signs suggest something very dangerous: that the virus is able to reach the brain and attack directly the neurons. This could make it necessary for us to rethink some of the treatments for Covid-19 (1). An example: the body’s immune system fights against the virus. After looking at the responses against Covid-19 in the brain, antibodies against the coronavirus have been detected in the patients’ spinal fluid. This indicates that there may be some specific immune response in the CNS of several or many patients and suggests that the virus can cause neurological damage, in the nervous system.

This is a cause for concern. In the first wave, we already began to see patients with different symptoms. Some of them died without giving them time to be taken to the hospital or even taken down to the ICU, something that the health care providers commented on with horror. And then some would show unusual movements, headaches or dizziness. Others had seizures and others suffered brain haemorrhages or strokes, even young people with no underlying conditions, but the most common neurological symptoms have been loss of smell, anosmia and loss of taste, ageusia 1.

The official symptoms listed by the World Health Organization initially included fever, tiredness, dry cough, sore throat, shortness of breath, aches and pains, and sometimes a runny nose or nausea or diarrhoea. But in response to increasing reports of people who have lost their sense of taste and smell, the WHO and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have expanded their list of symptoms to include loss of both of these senses. The temporary loss of smell is bearable, although quality of life is lost, many of our enjoyments, food, a walk in the country, are based on our smell. If it becomes permanent there are health risks such as eating bad food or not being aware of having left the kitchen gas on. In China a study of 214 patients showed that 5.1% had had anosmia and 5.9% had had ageusia. Although there are data that the numbers may be higher: a survey of 417 people treated in twelve European hospitals (Belgium, France, Spain and Italy) found that 85.6% and 88.0% of patients reported olfactory and gustatory dysfunctions, respectively. There was a significant association between both disorders 2.

A group from Yale University in the United States has analyzed the neurotrophic effect of coronavirus in three ways: in mouse brains, in human nerve tissue from autopsies, and in organoids that would be like tiny artificial brains, microscopic balls of neurons and other cells 34. In other tissue, samples could be successively extracted and the evolution of the infection could be followed. However, since we are dealing with the brain, we have an added problem, which is that it is not possible to extract samples from a patient. Using human material postmortem also has its difficulties. Not everyone is willing to donate their own brain or that of a family member; that person has died in an extreme situation that can affect what is observed in their neurons and there is also prevention by pathologists because if the brain is removed, electric saws are used to open the skull and that can generate aerosols and contaminate the room and the equipment. It is not as easy as it seems.

Several important things. One, is that the scientific community has begun to accept the theory of neuroinvasion, that the virus could be reaching the brain. After the same gateway that the coronavirus uses to enter the lungs, the ACE2 receptors, it uses them to infect the neurons and then, once inside them, it takes advantage of the machinery of the nerve cell to make copies of itself. And also, in the studies on the mice they were able to see that the blood supply of the brain is reorganized in response to the lack of oxygen that is generated by the situation in the lungs. And finally, something that has left scientists puzzled: after the coronavirus infects a certain neuron, something affects those around it, which are the ones that die.

The hypothesis of these researchers is that the cell that is infected by the virus enters a kind of hypermetabolic state, it would be to say in a simple way, hyperactive and that would make it consume the nutrients that the cells around it need to survive. It is believed that after the viral infection the neurons adapt and modify their metabolic routes. The response is similar to that seen in a stroke, where there is neural damage due to a problem in the blood supply and a reduced oxygen supply (1).

The presence of coronavirus RNA in the cerebrospinal fluid of a patient with covid-19 supports the theory of a neurotropic process of SARS-CoV-2. However, it is not known how the virus reaches the neurons. Three possibilities are that it is a hematogenous spread, through the blood vessels, a process of neuronal retrograde spread, from the axons that innervate the parts of the body to the neurons located in the central nervous system or that it is through the olfactory system, where the olfactory receptor neurons are directly exposed to the air.

We must think that it is possible that some of the people who survive Covid-19 are going to have long-term problems because of that neurological damage and are going to need neurorehabilitation for long periods. We hope that, as William Faulkner said in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, humanity will prevail.

References

- Hamzelou J (2020) Virus on the brain. New Scientist 246(3284): 34-38. ↩

- Lechien JR, Chiesa-Estomba CM, Place S, Van Laethem Y, Cabaraux P, Mat Q, Huet K, Plzak J, Horoi M, Hans S, Rosaria Barillari M, Cammaroto G, Fakhry N, Martiny D, Ayad T, Jouffe L, Hopkins C, Saussez S; COVID-19 Task Force of YO-IFOS (2020) Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of 1420 European patients with mild-to-moderate coronavirus disease 2019. J Intern Med 288(3): 335-344. ↩

- Pacheco MF (2020) Coronavirus could invade the brain, two Yale studies suggest. Yale Daily News September 28. ↩

- Zhou Z, Kang H, Li S, Zhao X (2020) Understanding the neurotropic characteristics of SARS-CoV-2: from neurological manifestations of COVID-19 to potential neurotropic mechanisms. J Neurol 267(8):2179-2184. ↩

1 comment

[…] SARS-COV-2 koronabirusa, covid-19aren eragilea, gorputzeko hainbat organotan ditu efektuak, sintoma eta ondorio andanarekin. Oraindik ikasten gabiltza, baina gauza batzuk ezagutzen hasi gara, eta ez dira berri onak. José Ramón Alonsoren Coronavirus in the brain […]