First 2D discrete time crystal on a quantum computer

First 2D discrete time crystal on a quantum computer

If you’ve ever sat by a quiet pond and tapped the surface of the water with your finger once every second, you’d expect to see a ripple travel outward once every second. In the world of classical physics, the effect follows the cause in a predictable, rhythmic march. But imagine for a moment that you tapped the water every second, yet the ripples only appeared every two seconds. This would feel like a glitch in the matrix—a fundamental breakdown of how we expect time and motion to behave. This “glitch” is essentially what physicists call a discrete time crystal.

Discrete time crystals

To understand a discrete time crystal, we first have to think about what a normal crystal is. A diamond or a grain of salt is a “space crystal” because its atoms are arranged in a repeating pattern that breaks the “spatial symmetry” of the universe. If you move through empty space, every point looks the same, but inside a crystal, some points have atoms and some don’t.

A time crystal does the same thing, but with time.

Imagine you have a collection of quantum bits (qubits) and you “kick” them with a pulse of energy every second. Normally, you’d expect the system to respond every second, or perhaps eventually settle into a messy, thermalized state where the “kicks” just turn into heat. But a time crystal is stubborn. It begins to oscillate at a different frequency than the one you’re driving it with, for example, returning to its original state only every two kicks. It breaks the so-called “discrete time-translation symmetry” of the drive. It’s like hitting a bell once a second, but the bell only rings once every two seconds, and it keeps that perfect, weird rhythm forever without absorbing heat.

The secret sauce of 1D systems

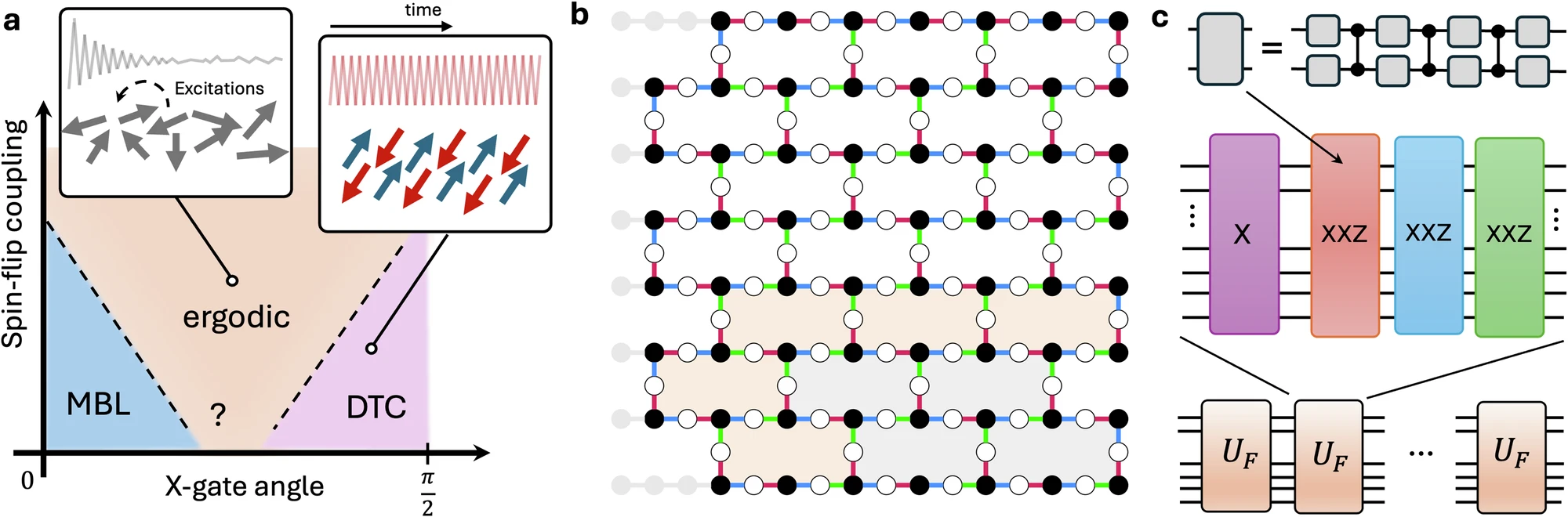

Until recently, most experimental time crystals were essentially one-dimensional, basically a single string of atoms. While impressive, 1D systems are “easier” for physicists because they are more prone to a phenomenon called Many-Body Localization (MBL). MBL is the “secret sauce” that keeps a time crystal from melting. It acts like a layer of internal friction that prevents the energy from the external kicks from spreading out and turning into heat.

Moving to two dimensions (a 2D grid) is a massive leap in difficulty. In 2D, energy has many more paths to travel, making it much harder to keep the system “localized” and prevented from melting into a boring, hot soup.

2D discrete time crystals exist

Now, a team of researchers has used the heavy hexagonal lattice of an IBM quantum processor (a complex, honeycomb-like arrangement) to prove that these time-crystalline patterns could survive and thrive in a more complex, 2D landscape 1.

Heisenberg coupling, however, is much more complex; it means the neighbors influence each along all three axes (X, Y, Z). In the anisotropic version, the strength of that influence varies depending on the direction, making interactions more complex and closer to those in real materials.

By using a combination of direct experiments on the quantum chips and advanced mathematical simulations to double-check the results, the researchers mapped out exactly where this time crystal lives. They found that if they changed the “kicks” or the interactions too much, the crystal would eventually “melt” into a thermal state or get stuck in a “glassy” state where the rhythm was lost. But in that goldilocks zone, the time crystal persisted: It essentially became a 2D sheet of quantum bits that tick-tocked in a perfect, synchronized rhythm that was slower than the pulses they were being hit with.

Quantum computers as physics laboratories

This is an impressive deal for two reasons. First, it proves that time crystals are much more robust than we thought. They aren’t just a 1D curiosity; they can exist in higher dimensions even when the internal interactions are incredibly complex. Second, it shows that we can use modern quantum computers as “digital laboratories” to discover phases of matter that might be impossible to find in a natural mineral. We are no longer just observing the materials nature gives us; we are using quantum hardware to “program” entirely new physics.

Protecting quantum information

This research pushes us closer to a future where we can “protect” quantum information. One of the biggest hurdles in building a useful quantum computer is that quantum states are incredibly delicate as they tend to vanish the moment they interact with the outside world. If we can understand how time crystals stay organized and resist “melting” or heating up, we might be able to use those same principles to build quantum memories that are naturally shielded from the chaos of the environment. We are learning how to make the “spooky” laws of quantum mechanics work for us, turning a rhythmic glitch in time into a building block for the next generation of technology.

References

- Eric D. Switzer, Niall F. Robertson, Nathan Keenan, Ángel Rodríguez-Alcaraz, Andrea D’Urbano, Bibek Pokharel, Talat S. Rahman, Oles Shtanko, Sergiy Zhuk & Nicolás Lorente (2026) Realization of two-dimensional discrete time crystals with anisotropic Heisenberg coupling Nature Communications doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-67787-1 ↩