Challenging Bredt’s rule

Challenging Bredt’s rule

In the world of organic chemistry, some rules are taught as absolute boundaries. One of the most famous is Bredt’s rule, a guideline that has dictated the limits of molecular architecture for nearly a century. This rule essentially places a “keep off the grass” sign on certain parts of a molecule, specifically forbidding the formation of double bonds at the bridgehead positions of small bicyclic systems. These bridgeheads are the atoms where two or more rings in a molecule meet, acting like the structural joints of a complex 3D frame.

Understanding the limits of molecular strain

The reason for this prohibition is purely geometric. For a double bond to be stable, the two involved carbon atoms must sit in a flat, planar arrangement. This allows their electron clouds (known as p-orbitals) to align perfectly and share electrons. In a small, rigid, two-ring system, the surrounding cage of atoms is simply too tight to allow for this flatness. Forcing a double bond into that position would be like trying to shut a door when the hinges are severely bent, it creates immense internal strain that usually causes the molecule to fall apart or prevents it from forming at all.

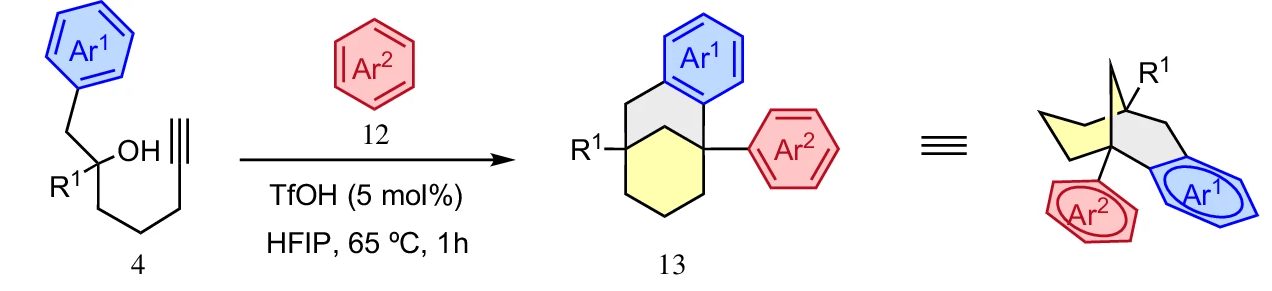

However, a recent study 1 has used this “forbidden” rule not as a barrier, but as a roadmap for discovery. By carefully manipulating reaction conditions, researchers have developed a sophisticated way to build complex bicyclo[3.3.1]nonane derivatives, which are rigid, three-dimensional structures. This achievement is significant because it challenges our traditional understanding of how much strain these molecules can actually tolerate.

How woud a vinyl cation react?

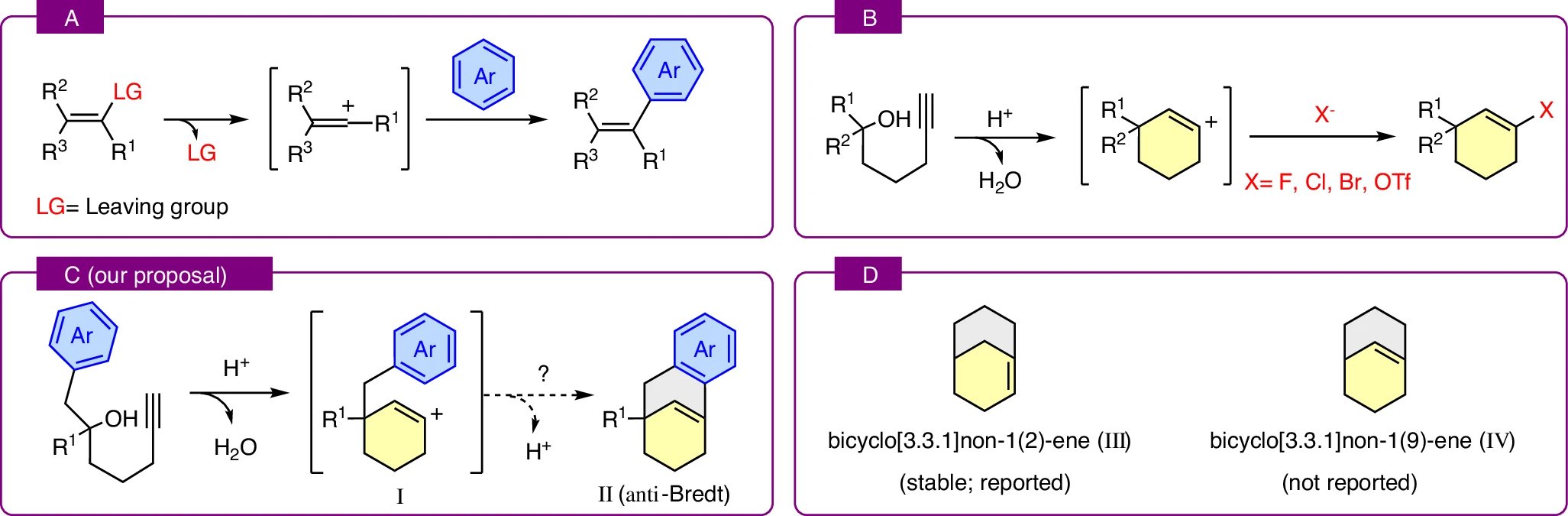

The journey begins with relatively simple starting materials called alkynol derivatives. These molecules are interesting because they contain both an alcohol group and a carbon, carbon triple bond. When the scientists introduced a powerful acid (specifically triflic acid) to these molecules, the alcohol group was forced to leave, creating a highly reactive, positively charged center known as a carbocation. These carbocations are famously “thirsty” for electrons and will often rearrange the entire skeleton of a molecule just to find stability.

In this specific reaction, the nearby triple bond (the alkyne) quickly captures that positive charge. This creates a more specialized and much rarer species called a vinyl cation, where the positive charge sits right next to a double bond. Usually, these vinyl cations are fleeting and difficult to study, but they are the key to unlocking the complex ring systems the researchers were targeting.

The team’s ultimate goal was to see if this cation could react with an aromatic ring located elsewhere on the same molecule. This is an “intramolecular” reaction, meaning the molecule essentially folds in on itself to create a new ring. If the reaction had proceeded in the most direct way possible, it would have produced an “anti-Bredt” alkene, a molecule with a double bond at the bridgehead that should be too strained to exist.

Challenging traditional stability assumptions

Interestingly, the simple anti-Bredt product was not what the researchers found. Instead, they discovered that the reaction took a clever detour. By using a special solvent called hexafluoroisopropanol, or HFIP, they were able to stabilize the high-energy intermediates. HFIP is a unique tool in modern chemistry because it can surround and protect positively charged molecules, giving them enough time to rearrange into more stable forms.

Mechanistically, the HFIP acts as a temporary “reservoir”. It reacts with the vinyl cation to form a neutral intermediate called an enol ether. This is a brilliant chemical workaround. Instead of forcing the molecule to pass through a highly strained, unstable “forbidden” state, the enol ether stores the molecule’s energy safely. From there, the molecule can be reactivated by the acid to undergo a final closure into a stable, three-dimensional bicyclic structure that does not violate the rules of geometry.

Three-dimensional tools for drug design

Beyond just making new molecules, this work has changed how we think about the “forbidden” zones themselves. Computational studies performed by the team suggest that some of these anti-Bredt frameworks might actually be more stable than we previously thought. This suggests that under the right conditions, chemists might eventually be able to isolate and use these rare, high-energy structures.

The practical payoff for this research is found in medicinal chemistry. The resulting bicyclo[3.3.1]nonane cores are rigid and bulky, unlike the flat, two-dimensional rings like naphthalene that are common in many drugs. In the world of drug design, these 3D shapes are called bioisosteres. They can mimic the biological activity of flat molecules while often being easier for the body to dissolve and harder for metabolic enzymes to break down. By turning a rigid rule into a guide for exploration, these researchers have provided a new toolkit for building the medicines of the future.

Author: César Tomé López is a science writer and the editor of Mapping Ignorance

Disclaimer: Parts of this article may have been copied verbatim or almost verbatim from the referenced research paper/s.

References

- O. Garcia-Pedrero, P. Pardo, N. Alberro, F. P. Cossio, and F. Rodriguez (2025) Challenging the Bredt’s rule in an acid catalyzed cationic cyclization to get bicyclo[3.3.1]nonane derivatives Nat. Commun. doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-65574-6 ↩