In how many ways can you fold a strip of stamps?

When was the last time you used a postage stamp? Even if it was a long time ago, you may have hold in your hands a strip of stamps. Maybe you have even tried to fold it into a stack, one stamp wide, so that the strip was easier to store. Have you ever wondered how many ways are there to do so?

This problem was stated by Lucas 1 in 1891 and today, more than 120 years later, there is still no formula answering the question. A recent paper by Stéphane Legendre2 reviews the problem and adds some new results.

First, the labeled case is considered, where the stamps can be distinguished (as in the previous picture). For a mathematical model, you can label them ![]() consecutively along the unfolded strip. The goal is then to find all the possible stacks being

consecutively along the unfolded strip. The goal is then to find all the possible stacks being ![]() stamp wide and

stamp wide and ![]() stamps tall.

stamps tall.

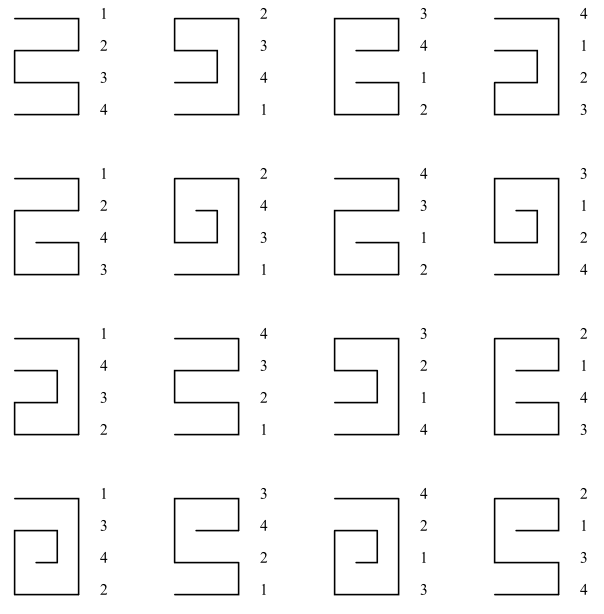

The following figure shows all the possibilities for a strip of ![]() stamps. Horizontal segments represent the stamps, while vertical segments represent the perforations. In addition, the label of each stamp is depicted next to it.

stamps. Horizontal segments represent the stamps, while vertical segments represent the perforations. In addition, the label of each stamp is depicted next to it.

Those strings of numbers suggest to consider a useful notion in Mathematics, that of a permutation. Reading the labels downwards, from the top of the stack to the bottom, we can unambiguously identify a folding with a permutation. Interestingly, not all the possible permutations lead to feasible foldings: For an example, the permutation ![]() is not a folding because a crossing would show up.

is not a folding because a crossing would show up.

The question of which permutations do correspond to a folding was settled by Koehler3 in 1968:

A permutation

is a folding if, and only if, neither the inequalities

nor any of their circular rearrangement occur with

and

having both the same parity (odd or even).

Note that in the example ![]() above, the inequalities arise for

above, the inequalities arise for ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

As for the question of the number of foldings, Sainte-Laguë4 observed in 1937 that:

The number of elements of the set

of foldings of

labeled stamps is

,

where

is the number of elements of the set

of

-foldings of type

, i.e., with stamp 1 on top.

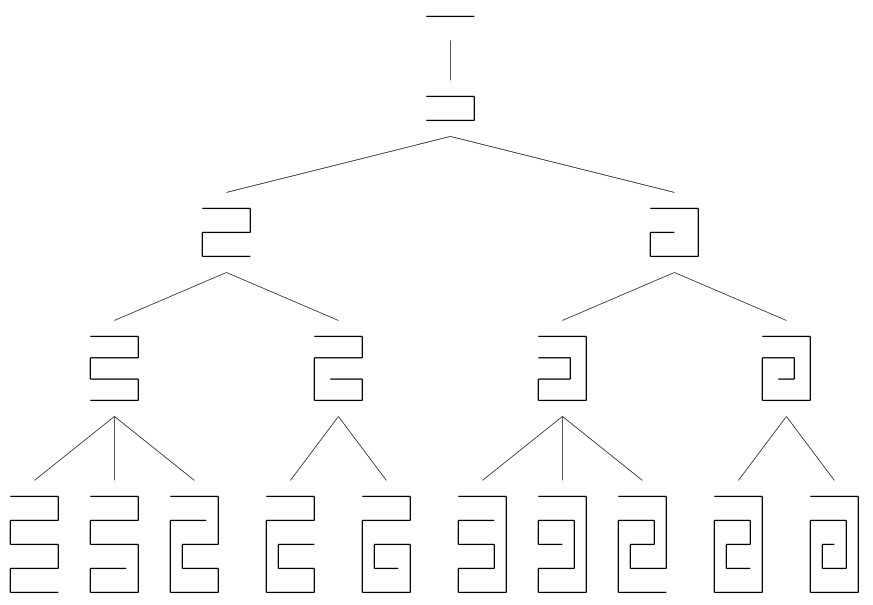

This allows to focus on the set ![]() which, usefully, can be constructed in an inductive way by using a tree of depth

which, usefully, can be constructed in an inductive way by using a tree of depth ![]() . The following figure shows the tree describing the sets

. The following figure shows the tree describing the sets ![]() for

for ![]() .

.

It turns out that, below the second level, the left and the right subtrees are topologically identical. The reason is that if ![]() is a folding, then the “reversed” permutation

is a folding, then the “reversed” permutation ![]() is also a folding.

is also a folding.

Thus, each folding ![]() in the left subtree is uniquely associated with a folding

in the left subtree is uniquely associated with a folding ![]() in the right subtree. This implies that

in the right subtree. This implies that ![]() is even for

is even for ![]() and, more important, that the problem can be reduced to focusing on foldings of type

and, more important, that the problem can be reduced to focusing on foldings of type ![]() . Lunnon5 proposed an algorithm for listing these foldings, using a depth-first search.

. Lunnon5 proposed an algorithm for listing these foldings, using a depth-first search.

The above results have allowed to compute the number ![]() of labeled foldings up to

of labeled foldings up to ![]() , for which 37384929247793935264200 possibilities arise. The whole list of numbers can be checked as the sequence A000136 of the On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences6.

, for which 37384929247793935264200 possibilities arise. The whole list of numbers can be checked as the sequence A000136 of the On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences6.

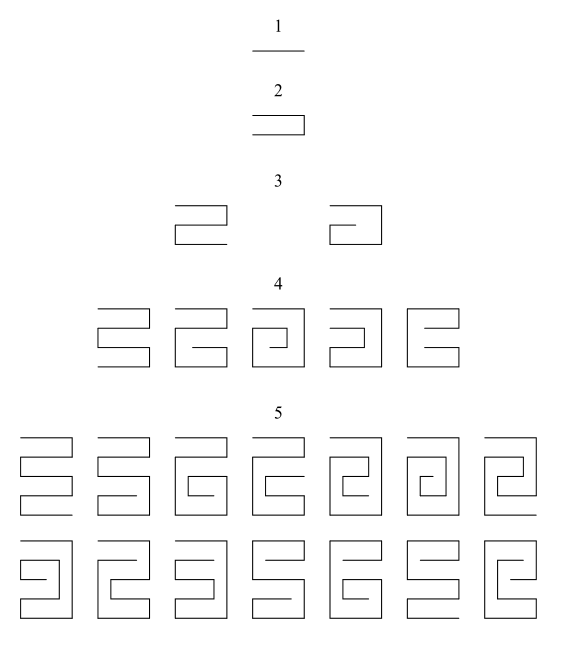

The case of blank stamps is also considered by Legendre. In this case the stamps are not labeled, so that the foldings have to be distinguished according to their shapes. In particular, different labeled foldings might lead to the same unlabeled folding. For an example, consider the second and fourth cases (left to right) in the first row of Figure 2, being one a reflection of the other.

Luckily enough, the corresponding set of unlabeled foldings can also be constructed inductively using a tree. The following figure shows the foldings of ![]() blank stamps for

blank stamps for ![]() .

.

Again, the number ![]() of different unlabeled foldings is known up to

of different unlabeled foldings is known up to ![]() , for which 9346232311986692725748 possibilities arise. The whole list of numbers is available as the sequence A001011 of the On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences7.

, for which 9346232311986692725748 possibilities arise. The whole list of numbers is available as the sequence A001011 of the On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences7.

Provided that there is no formula for the number of foldings, a classical question is wondering about the asymptotics. I.e., how is this number growing when ![]() grows? Legendre cites several authors to support the general believing that the number of

grows? Legendre cites several authors to support the general believing that the number of ![]() -foldings is of the form

-foldings is of the form ![]() , with

, with ![]() being constants which, of course, are not known. That is, an exponential growth.

being constants which, of course, are not known. That is, an exponential growth.

In order to provide an estimation of ![]() , Legendre shows that the number of foldings for all the cases considered above,

, Legendre shows that the number of foldings for all the cases considered above, ![]() , share the same

, share the same ![]() . Then, he uses the best known values to obtain an estimation up to the tenth decimal position.

. Then, he uses the best known values to obtain an estimation up to the tenth decimal position.

Overall, this is a nice review of a problem which, despite seeming harmless, explodes for not so large cases due to the exponential growth of the number of combinations.

References

- E. Lucas. Théorie des Nombres, Vol. 1, Gauthier-Villars, Paris, 1891, page 120. ↩

- Legendre S. (2014). Foldings and meanders, Australasian Journal of Combinatorics, 58 (2) 275-291. DOI: ↩

- J.E. Koehler. Folding a strip of stamps, Journal of Combinatorial Theory, 5:2 (1968), pages 135-152. ↩

- A. Sainte-Laguë. Avec des Nombres et des Lignes, Vuibert, Paris, 1937, pages 147-162. ↩

- W.F. Lunnon. A map folding problem, Mathematics of Computation, 22:101 (1968), pages 193-199. ↩

- Sequence A000136, On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences. ↩

- Sequence A001011, On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences. ↩

8 comments

[…] ¿De cuántas formas puedes plegar una tira de sellos? […]

[…] ¿Cuándo fue la última vez que usaste un sello de correos? Incluso si hace mucho, o nunca lo has hecho, puede que hayas tenido en tus manos una tira de sellos. Puede que incluso hayas intentado plegarla para que […]

[…] Noiz erabili duzu azkenekoz posta-seilu bat? Agian, asko dela edota inoiz ez baina baliteke zure esku artean eduki izana seilu tira bat. Behar bada tira tolesten ahalegindu zara, seilu bakar baten bateratuta gelditu dadin eta horrela errazago gorde. Baina […]

[…] para que ocupe el menor espacio posible, tiene una complejidad matemática no trivial, y saber cuántas maneras diferentes de doblarla existen es un interesante problema de combinatoria… cuya solución aún no ha sido encontrada […]

[…] so that the strip was easier to store. Have you ever wondered how many ways there are to do so? This post reviews a recent research survey about the […]

[…] In how many ways can you fold a strip of stamps? […]

[…] In how many ways can you fold a strip of stamps? […]

[…] In how many ways can you fold a strip of stamps? […]