Turning malignancy into normalcy: A computational path to cancer cell reversion

Turning malignancy into normalcy: A computational path to cancer cell reversion

Author: José R. Pineda got his Ph.D. from University of Barcelona in 2006. Since 2007 he has worked for Institut Curie and The French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission. Currently he is a researcher of the UPV/EHU. He investigates the role of stem cells in physiologic and pathologic conditions.

Throughout the relentless struggle against cancer, conventional medicine has largely depended on aggressive methods of elimination—surgical removal, radiation, and chemotherapy—aimed at eradicating malignant cells before they can overwhelm the patient. While these approaches have proven effective in many cases, they often come at a steep cost, damaging healthy tissue and leaving patients vulnerable to recurrence. In a groundbreaking development from the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, researchers led by Professor Kwang-Hyun Cho explore 1 a radically different strategy: instead of destroying cancer cells, they propose reprogramming them. Their research into colon cancer revealed that, under specific conditions, malignant cells can be guided back to their original, healthy state. This represents a fundamental shift in cancer treatment philosophy—from annihilation to rehabilitation.

This new perspective invites a reconsideration of the core question of oncology. If cancer arises from a breakdown in cellular programming, could the solution lie in repairing that code rather than eliminating the cell altogether? To grasp the significance of this approach, it’s important to understand how cancer originates. At its essence, cancer is a result of dedifferentiation, where specialized cells lose their identity and function. In the colon, for example, healthy epithelial cells perform distinct roles. When these cells abandon their specialization and focus solely on survival and replication, they become cancerous. Traditional treatments aim to eliminate these rogue cells, but they often harm other rapidly dividing cells in the process, such as those in the bone marrow or hair follicles. Moreover, cancer’s ability to adapt means that resistance to treatment and relapse remain persistent challenges.

Reprogramming offers a promising alternative. The concept is both simple and profound: cancer cells are not inherently destructive—they are misdirected. If scientists can identify the molecular instructions these cells have lost, they may be able to redirect them toward normal behavior. The result is a cell that no longer acts like a tumor. Professor Cho’s team has not only theorized this possibility but has demonstrated it with remarkable precision. Their work relies on the computational platform, BENEIN (short for “Boolean Network Inference and Control”). Using Boolean logic, where genes are treated as either “on” or “off,” the BENEIN system can simulate thousands of genetic scenarios. This allows researchers to test combinations of gene activation and silencing virtually, without the need for physical experimentation. Such precision modeling minimizes trial-and-error and enables highly targeted interventions. Thus, the computational platform is designed to analyze the gene networks that define cellular identity and their astonishing results were published in the prestigious journal Advanced Science [1]. BENEIN framework uses single-cell transcriptomic data to identify master regulatory genes and Cho and collaborators used this strategy to identify (and then, to revert) the genetic regulation that determines whether a cell behaves normally or becomes cancerous.

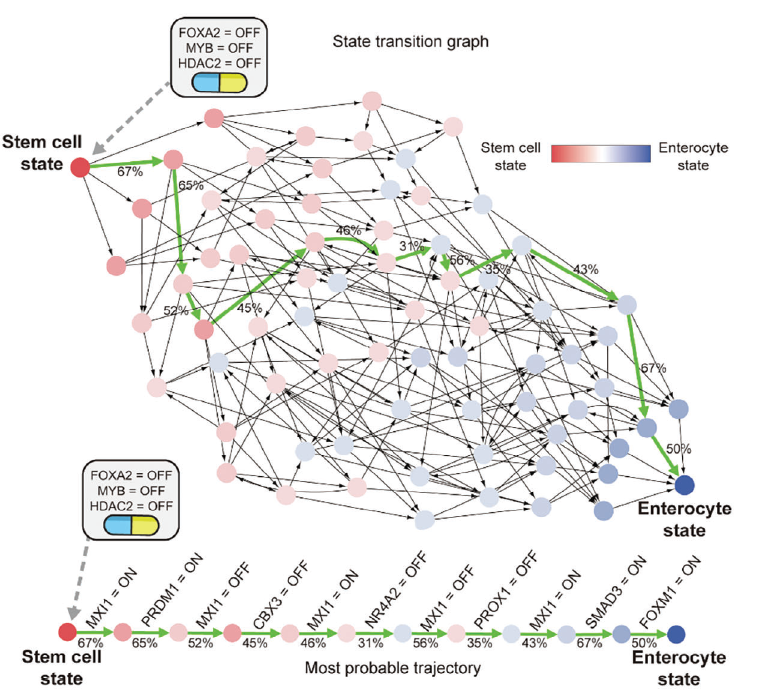

They started by looking at the activity of genes in individual cells, separating each cell’s gene activity into two stages: before and after a change. Then, they built a map of how genes influence each other. They simplified this map to focus on the most important parts and turned it into a model that uses simple ON/OFF logic to describe gene behavior. Finally, they identified which genes (called master regulators) need to be controlled to guide cells toward a healthy state. They looked at thousands of cells and tracked how they naturally change into enterocytes (a type of healthy colon cell). They built a model showing how genes interact during this process. The model matched well with real data, showing that it could accurately simulate how stem cells become enterocytes. They also identified stable states (called attractors) that represent different cell types and showed how cells move from one state to another during differentiation. The analysis using BENEIN platform identified three genes: MYB, HDAC2, and FOXA2 known to contribute to tumor growth and abnormal cellular behavior. Next, they decided to silence all three genes simultaneously in HT-29, CACO-2, and HCT-116 colon cancer cell lines. They observed a dramatic transformation by turning off MYB, HDAC2, and FOXA2 on these cells observing that closely matched the behavior of healthy enterocytes reducing their proliferation. But why these genes were so important? These genes sit at the top of the gene network, meaning they control many other genes. When these three are turned off, they strongly influence the rest of the network, pushing cells toward a healthy state. They also tested this in lab-grown normal colon cells and found that the changes predicted by the computer model matched what happened in real cells. This results confirmed that MYB, HDAC2, and FOXA2 genes are key drivers of cell behavior.

Next they used in vivo mice grafts in which tumors made from these modified cancer cells were much smaller than those made from untreated cancer cells. This result showed that controlling these genes not only changes cell behavior but also reduces cancer growth in living organisms. Their results highlighted that when the three master genes were turned off, cancer cells began to look and act like normal colon cells. At the same time, cancer-related pathways like MYC and WNT become less active. This transformation was confirmed both by looking at gene activity and by measuring protein levels. Furthermore, they also showed that simply increasing these genes doesn’t make cells more cancerous, reinforcing that their inhibition is key to reversion.

In conclusion, this new approach marks a significant advancement in personalized medicine, offering the potential to tailor treatments not just to a cancer type, but to the unique genetic architecture of an individual’s tumor. The most immediate benefit would be a significant reduction in side effects. Although challenges remain on the path ahead, by proving that colon cancer cells can be methodically guided back to a normal-like state, the researchers have gone beyond introducing a novel technique. This strategy replaces the traditional arsenal of toxic interventions with a blueprint for biological correction. Whether this approach evolves into a mainstream standard or remains a specialized option will depend on thorough validation, clinical efficacy, and successful translation into practice. Yet, the current evidence is encouraging.

References

- Jeong-Ryeol Gong, Chun-Kyung Lee, Hoon-Min Kim, Juhee Kim, Jaeog Jeon, Sunmin Park, Kwang-Hyun Cho (2025) Control of Cellular Differentiation Trajectories for Cancer Reversion. Adv Sci doi: 10.1002/advs.202402132. ↩