The bodyguard

The bodyguard

Ladybugs are beautiful beetles and many present what is called an aposematic coloration, bright and striking colors that warn: do not eat me, I am dangerous. When they are disturbed, they defend themselves with legs and jaws, expel a poison and their brightly colored elytra with black dots are a warning to anyone who tries to attack them: remember these colors and don’t try again. This is not an obstacle for Dinocampus coccinellae, a green-eyed parasitic wasp looking for an adult female ladybug, rarely a male or a juvenile.

This wasp lays an egg with its ovipositor in the soft tissues of the lower abdomen of the beetle. After 5-7 days the egg hatches and a first larva with large jaws emerges. The first thing that the wasp larva does is to eliminate other eggs or larvae that may be in the same animal. It does not want competition and as they say in Fortnite, “only one can survive”. Then it begins to feed on the fat and gonads of the ladybug. Over the course of 18-27 days, the wasp larva grows within the ladybug and goes through four larval stages in its development. When ready to emerge from the interior, the wasp paralyzes the ladybug and begins to tunnel outward. Once out, the wasp larva prepares a silk cocoon between the beetle’s legs. A solitary wasp cocoon is extremely vulnerable and will be eaten by any predator but the wasp has sought a formidable ally: the ladybug, who assumes a new role, after being a cradle and food, becomes a bodyguard 1. The ladybug surrounds the cocoon with its legs and its body and if any predator approaches the cocoon it will move its legs and face the attacker who in most cases will run away.

After 6-9 days the wasp emerges from the cocoon and begins its independent life. In some cases there is a happy ending for everyone; about a quarter of the ladybugs manage to go on living and come out of paralysis once the cocoon is empty. The rest die. But the process is, as in these cases, fascinating.

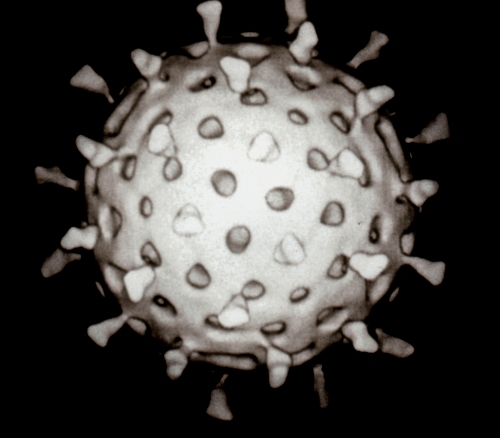

There was a question in this process that was temporalization. The ladybug doesn’t become a zombie until several weeks pass after the wasp has laid the egg. Nolwenn Dheilly and her group thought that maybe the wasp larva or ladybug made some toxic protein that built up over time until it caused the beetle to become paralyzed. They began to look for some suspicious gene activity that could give rise to a molecule with these characteristics and for it they analyze the transcriptome, sequencing the transcripts of RNA both in the ladybug and in the larva of the wasp. I explain it briefly: we have been sequencing for years, reading DNA and knowing the genes of a species. But many genes are not expressed or only expressed in some cells or at specific times, so it is also very interesting to know which DNA genes are transcribed into messenger RNA because it will give us a significant idea about the activity that is taking place. The set of all those messenger RNA transcripts is the transcriptome and when they analyzed it the researchers found, to their surprise, that the brains of the parasitized ladybugs were plagued with an unknown viral RNA, which was not present in healthy ladybugs. It was called the Dinocampus coccinellae paralysis virus, or DCPV 2.

The virus is stored in the oviduct of female parasitoids and transmitted to the host when the mother wasp lays its egg in the abdomen of its victim. At the same time the wasp injects the egg, a cocktail of chemicals and the virus into the ladybug. There is evidence that it is the virus that immobilizes the ladybug, protecting the wasp larva (and virus copies!) from intruders and predators.

Similar iflaviruses have been found in insects of economic interest such as the honeybee and the silkworm. However, in these cases the viruses are very pathogenic and cause the collapse of the colony, but that does not happen in the case of the parasite. In fact, no potential pathogenicity has been seen in the adults of D. coccinellae and it will be necessary to determine whether it is a case of parasitism, commensalism or mutualism. What has been verified is that the DCPV replicate in the cerebral ganglia of the parasitized ladybugs. There is therefore a neurotropism, they move specifically towards the nervous tissue and develop there. Curiously, a neurotropism associated with symptoms of paralysis has been found in other picorna-like viruses such as polio, the virus of lethal paralysis of aphids and the virus of chronic paralysis of bees.

A ladybug devours about 5500 aphids in a year, so any parasite that affects the survival, development and reproduction of ladybugs is a potential threat to agriculture. In the UK the infestation of the best-known ladybug, the seven-point Coccinella septempunctata, by D. coccinellae increased significantly during the 1990s, from 20% of adult animals to more than 70% which had a serious economic impact on English farmers because a significant proportion of ladybugs die and aphids benefit from it. That is why it is important to know more about these relationships between species.

The virus and the wasp have common interests: turning the ladybug into a bodyguard that will protect the maturation of the wasp and more wasps means more viruses. In the end we thought that the wasp was the one that manipulated the puppet but it seems that inside there is a puppeteer, the virus, which maybe is the one running the show.

References

- Weiler N (2015) Wasp virus turns ladybugs into zombie babysitters. Science ↩

- Dheilly NM, Maure F, Ravallec M, Galinier R, Doyon J, Duval D, Leger L, Volkoff AN, Missé D, Nidelet S, Demolombe V, Brodeur J, Gourbal B, Thomas F, Mitta G (2015) Who is the puppet master? Replication of a parasitic wasp-associated virus correlates with host behaviour manipulation. Proc Biol Sci 282(1803): 20142773. ↩

1 comment

[…] beste adibide esanguratsu baten berri ematen du Jose Ramon Alonso neurobiologoak Mapping Ignorance blogean, erasoaren atzean dauden mekanismo molekularrak bilatzen dituen ikerketa baten berri emateko. […]