Do I flower now or do I wait a little bit more?

Do I flower now or do I wait a little bit more?

Flowers are the reproductive organs of angiosperms (flowering plants) and flowering is therefore the phenomenon by which the undifferentiated cells from the meristems (similar to animal stem cells) differentiate into a floral meristem that will then produce the different components of the flower (sepals, petals, stamens and carpels). This transition from a plant vegetative to reproductive stage is a central event in the life cycle of plants and needs to be tightly controlled to avoid flowering under unfavorable conditions. In fact, the success of reproduction of many plants depends in the synchronized flowering of all the individuals from the same population.

This transition from vegetative to reproductive stage is affected by environmental factors such as photoperiod (day-length) and temperature and signals within the plant like hormones. These factors assume the role of checkpoints to induce flowering in the correct time. Flowering in the wrong time can have great economic implications in agriculture, for example, warm periods in winter can confuse the plants and made them to flower too early with the risk of being exposed to later frost periods that can even provoke flowers death and thus, this can be traduced in a complete loss of the plants and trees grains and fruits production.

In 1936 it was proposed by the Russian scientist Mikhail Chailakyan that a substance could act as a mobile signal involved in flowering, that he named “florigen”. Many research groups all over the world have tried for a long time without success to identify this molecule; the inconsistent results found led even to suggest that florigen did not exist. However, more than 60 years later, in 1999 it was discovered in the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana a protein that acts as florigen, called Flowering Locus T (FT).

A. thaliana is a small plant, also known as thale cress. It is an annual plant that belongs to the family of Brassicaceae (broccoli, radish, cabbage, rapeseed, etc…). The genome of A. thaliana was the first one being fully sequenced and has become a popular tool for understanding the molecular biology of a great number of plant traits.

Coming back to flowers; FT production increases in relation with day-length and it is transported from the leaves, via the phloem, to the shoot apical meristem where it acts as inductor of flower development. However, as stated before not only light is essential for flower development but also temperature, age, sugars, hormones and others make the transition to flowering a complex process involving the convergence of multiple signals.

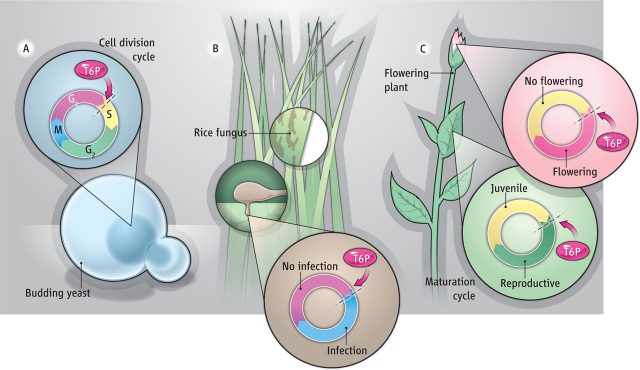

In February a study 1 performed by a german research group made a significant contribution to our understanding of flowering switch on. In this work, Wahl and collaborators describe how the plant metabolic status interferes with the developmental decision of entering into flowering or not. Wahl et al., show how this is achieved through a low-abundant carbohydrate, the sugar phosphate Trehalose-6-phosphate (T6P).

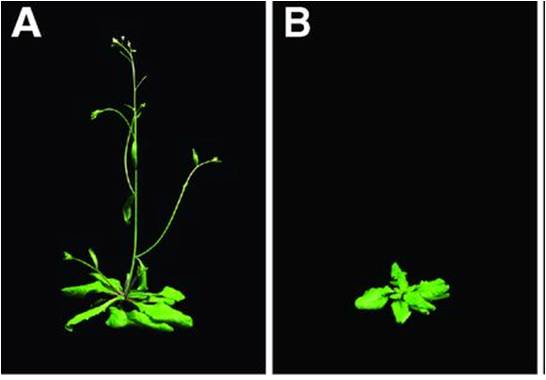

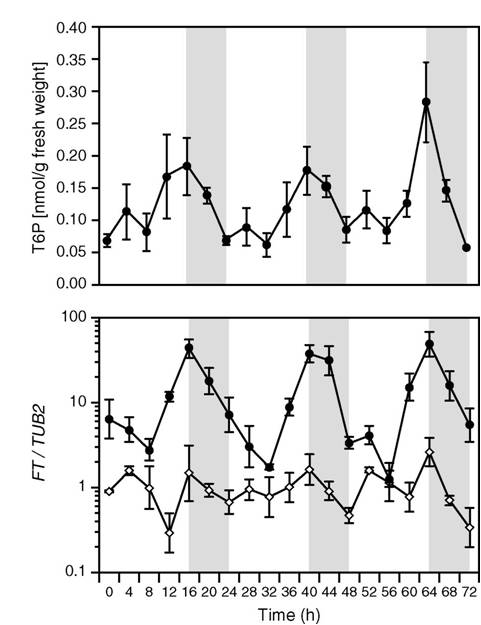

Trehalose is a disaccharide present in all animals and plants at trace levels, except vertebrates where it has not been detected. T6P was previously proposed as signalling molecule in carbon signalling. The synthesis of T6P is catalyzed by the trehalose-6-phosphate synthase enzyme (TPS). Genetically modified A. thaliana plants with reduced levels of TPS expression presented a dramatic delay in flowering time, giving an important cue of T6P involvement in flower development (Figure 2). Interestingly, Wahl et al, observed that T6P content follows a circadian rhythm across the day length with a maximum level at the end of the day, this is a common behaviour of different cell components associated to plant circadian clock, like for instance FT gene activity (Figure 3). By the use of different genetic approaches, Wahl et al., were able to demonstrate that T6P is directly involved in FT gene expression regulation.

Interestingly, Wahl et al. also observed that T6P interferes with flower signals others than photoperiod. They showed that TPS is expressed in the shoot apical meristem and that T6P levels where correlated in the meristem with the plant´s carbon status. Moreover, the presence of T6P in the meristem was shown to be essential for flower development.

FT induction has been shown to be a key signal to induce flowering, the induction of FT was previously shown to increase when increasing day length (environmental signal) in spring and now Wahl et al. have observed that an internal plant signal, an optimum sugars level, indicated by T6P also regulates FT. Thus, T6P creates a link between these two signals: the carbohydrate status (or energy status) and FT-flowering pathway. Thus, T6P provides an idea to ascertain that flowering is induced when the conditions are optimal, this means a minimum day-length and a good plant carbon status to support flowering which is a high-energy demanding process and thus to maximize the probability of plant reproduction.

Overall, the work of Wahl et al., makes a substantial contribution to our knowledge about plant flowering and provides a novel cue about the complexity of plant reproduction and organs development.

References

- Wahl V, Ponnu J, Schlereth A, Arrivault S, Langenecker T, Franke A, Feil R, Lunn JE, Stitt M, Schmid M (2013) Regulation of flowering by trehalose-6-phosphate signaling in Arabidopsis thaliana.Science 339: 704-7. ↩

1 comment

Thank you Daniel. Nice and clear post.