The brain has a direct connection to the lymphatic system

The brain has a direct connection to the lymphatic system

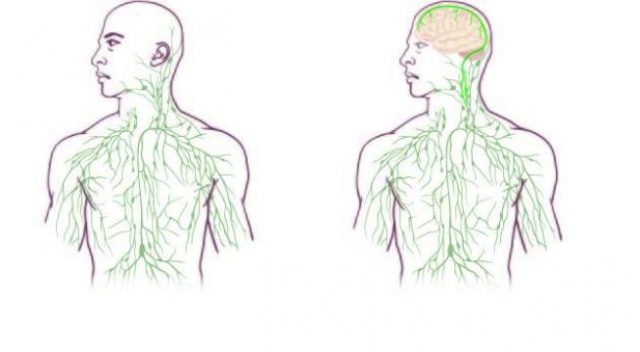

The lymphatic system performs important immune functions, and runs parallel to the blood circulatory system to provide a secondary circulation that transports excess interstitial fluid, proteins and metabolic waste products from the systemic tissues back into the blood. For centuries, it was thought that the central nervous system lacks a lymphatic drainage system and the brain was therefore considered the only major organ that lacked a direct connection to the lymphatic system. Not any longer.

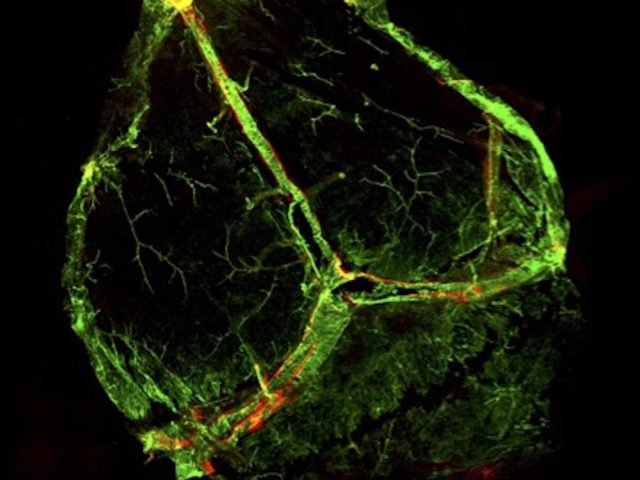

The lymphatic vessels are shown in red, almost invisible besides the blood vessels (in green). | Credit: Louveau et al (2015)

A recent study published in Nature 1 by a group from the University of Virginia reported something both simple —that there are lymphatic vessels in the dural sinuses— and revolutionary, in the sense that thousands of researchers have studied the brain anatomy without distinguishing them. The reason was that these vessels were «very well hidden» and they entered into the brain sinuses following major blood vessels, in close apposition to them and their thin walls were time after time overlooked.

The vessels are located in the meninges, the membranes covering the brain, a part that it is frequently discarded when the brain is prepared for analysis. Antoine Louveau, a postdoctoral fellow in Jonathan Kipnis’ Lab designed a system to mount a mouse’s meninges on a single slide so that they could be examined as a whole. A simple trick was used, they fixed the meninges with the skull cap so that the tissue is well fixated and hardened and its ultrastructure is perfectly preserved before dissecting it out 2.

Using immunohistochemistry, these lymphatic vessels express all the molecular markers characteristic of lymphatic endothelial cells such as Lyve-1, Prox1, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 and podoplanin. The presence of lymphatic endothelial cells in the meninges was also confirmed by flow cytometry. These vessels are able to carry both fluid and immune cells from the cerebrospinal fluid, and are connected to the deep cervical lymph nodes. They are devoid of smooth muscle cells and have no valves.

The meningeal lymphatic network appears to start from both eyes and track above the olfactory bulb before aligning adjacent to the sinuses. The authors were also able to live image these vessels, a crucial step to be confident about their function. It seems that the interstitial fluid from the brain parenchyma drain into the periphery after it has been drained into the cerebrospinal fluid through the recently discovered glymphatic system.

This study implies that the brain is like every other organ and it is connected to the peripheral immune system through meningeal lymphatic vessels. This fact opens completely new perspectives for the relationship between the nervous and the immune system and it is logic to consider that these lymphatic vessels may play a role in the constant immune surveillance that takes place within the meningeal compartment and, when they do not work properly, in every neurological disease that has an immune component. This discovery provides a simple answer to two previously unanswered questions: How did immune cells get in the brain, and how did they leave the brain? 3

The study was done in mice and it will be necessary to check that a similar system exists in humans but this discovery may have implications for different and important neurological diseases. Neurodegenerative diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease fall within a broad category referred to as proteinopathies, due to the common assemblage of misfolded or aggregated intracellular or extracellular proteins. According to the prevailing amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease, the aggregation of amyloid-beta (a peptide normally produced in and cleared from the healthy young brain) into extracellular plaques drives the neuronal loss and brain atrophy that is the hallmark of Alzheimer’s dementia. The proper functioning of the lymphatic clearance system may be necessary to remove the soluble amyloid-beta from the brain parenchyma and, therefore, the typical accumulations in Alzheimer’s patients would be due to lymphatic vessels not working properly. In addition, the lymphatic vessels may be affected by acute brain injuries such as ischemic stroke, intracranial hemorrhage or subarachnoid hemorrhage. Finally, it seems that the vessels look different with age, so they may also be involved in aging.

It will be necessary to change all textbooks since the absence of lymphatic vessels in the brain was a universally accepted dogma. All people thought hitherto that the body, and particularly the central nervous system, was carefully and completely mapped and then this surprise comes out with its important functional implications.

References

- Louveau A, Smirnov I, Keyes TJ, Eccles JD, Rouhani SJ, Peske JD, Derecki NC, Castle D, Mandell JW, Lee KS, Harris TH, Kipnis J (2015) Structural and functional features of central nervous system lymphatic vessels. Nature. doi:10.1038/nature14432. ↩

- University of Virginia Health System. (2015, June 1). Missing link found between brain, immune system; major disease implications. ScienceDaily. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2015/06/150601122445.htm ↩

- Friedman LF (2015) This stunning discovery about the brain will have scientists rewriting textbooks. Business Insider. June 3. ↩

1 comment

[…] Cuando parecía que ya no se podía saber nada más sobre la anatomía de un modelo animal archiestudiado como el ratón, va un grupo de investigadores y descubre ni más ni menos que el encéfalo tiene una conexión directa […]