Wikipedia as a cultural lens for mapping 17th-century

Wikipedia as a cultural lens for mapping 17th-century

If you’ve ever fallen down a Wikipedia rabbit hole—clicking link after link until you’re far from where you started—you’ve explored a network, much like physicists map connections in systems like the internet or ecosystems. Each Wikipedia article is a dot, each hyperlink a line connecting ideas. This vast web, built by millions of contributors, mirrors how ideas, people, and fields like art, science, and philosophy connect in human culture.

A recent study 1 asks a bold question: can Wikipedia’s link structure act as a map of cultural history? Could those links show how art, science, and philosophy interacted in 17th-century Europe, a time when these fields were thriving, sometimes together, sometimes apart? The researchers used Wikipedia not as a fact library, but as a living network to measure and visualize cultural connections.

Turning Wikipedia into a cultural map

The idea is simple yet clever: each Wikipedia article—about a person, idea, or movement—is a cultural “dot.” A link between articles suggests relevance, like influence or shared context. By mapping these links, we can build a network showing how knowledge connects historical figures and ideas, much like a subway map shows how stations link up.

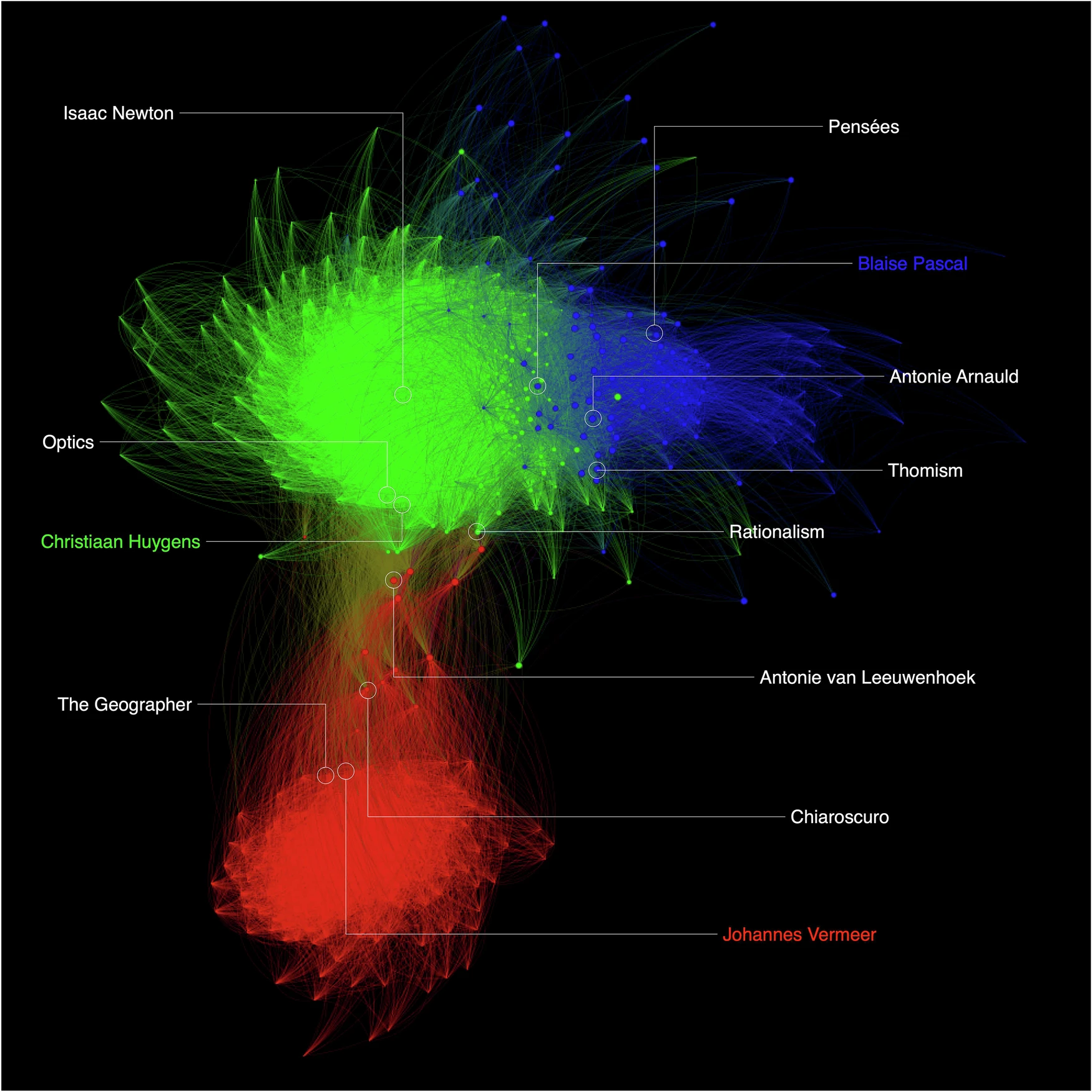

The team focused on well-documented figures born in Europe between 1600 and 1650, narrowing down from over 500,000 Wikipedia biographies to those with at least 100 outgoing links to ensure reliable data. They grouped these figures into three domains: artists (like painters or sculptors), scientists (like astronomers or physicists), and philosophers (like ethicists or thinkers). For each small trio—one artist, one scientist, one philosopher—they traced the web of Wikipedia pages linked to them, and the pages linked to those, up to two layers deep. Each mini-network is a snapshot of 17th-century cultural relationships, as seen through today’s digital encyclopedia. By combining hundreds of these snapshots, they created a large-scale picture of how these domains intertwine.

Quantifying cultural connections

With the network built, the researchers asked: how closely are these cultural areas linked? Do artists mostly connect to other artists? Are scientists and philosophers tightly knit? Are there “hubs”—people or ideas bridging different fields, like central stations in a transport network?

To find out, they measured how often articles shared similar “neighbourhoods” in Wikipedia’s web. If two articles frequently appear in related contexts, they’re considered “close,” even without a direct link. This captures deeper relationships, like ideas that belong to the same cultural conversation. From these patterns, they built a simplified network where the strength of each link shows how related two entities are, allowing them to analyse how clustered the network is, how much domains interact, and who acts as bridges.

The results paint a vivid picture of 17th-century culture, aligning closely with what historians know.

Distinct Communities

The network showed three clear groups: artists linked mostly to other artists, scientists to scientists, and philosophers to philosophers. About 88% of art-related links stayed within the art world, suggesting it was highly specialized. This reflects a shift from the Renaissance, when figures like Leonardo da Vinci blended art, science, and philosophy, to a time when fields were becoming more professionalized.

Cross-Connections

The strongest ties across domains were between science and philosophy. Think of figures like Galileo or Descartes, whose work mixed physics with big questions about reality. By contrast, art was more isolated, with fewer links to science or philosophy. This suggests science and philosophy were in active conversation, while art often stood apart.

Openness of fields

The study also measured how “open” each domain was—how often its members linked beyond their own group. Art was the most insular, sticking to its own circle. Science and philosophy were more outward-looking, with many articles connecting across boundaries. This mirrors the scientific revolution, when questions about knowledge and truth tied scientists and philosophers together.

Bridge figures and ideas

Most figures were specialists, highly connected within their own domain. But a few acted as bridges, linking different worlds. Big names like Newton, Pascal, or Leibniz stood out, but so did concepts like “mechanical philosophy” or lesser-known figures like Kepler, who appeared frequently across networks. These bridges, like hubs in a power grid, were rare but vital, tying together the cultural web.

Despite its biases

This study is exciting because it turns a cultural question—how ideas and fields connect—into something measurable, using data anyone can access on Wikipedia. It’s like using physics to map the flow of ideas, similar to how we study particles or networks. While Wikipedia reflects biases, like those of English-language editors or Western focus, its patterns still echo historians’ views of the 17th century.

For physicists and mathematicians, the method is the star: it uses network theory—tools we apply to everything from atoms to the internet—to study culture. It shows that cultural evolution follows patterns we can measure, like clusters or hubs. Imagine applying this to the 19th century, non-Western cultures, or today’s digital age to trace how fields split, merge, or evolve globally.

Culture as a living network

Ultimately, this research shows culture isn’t just a collection of ideas or artifacts—it’s a dynamic web, reshaped by communication and memory. Wikipedia captures this in real time, and by treating it as data, we uncover patterns once hidden: how knowledge organizes, fragments, and reconnects. Just as physicists map connections in the universe, this study maps the universe of human ideas. It’s a fitting nod to the 17th century, when curiosity began seeing the world as a web of connections—and now, through network science, we’re seeing culture the same way.

Author: César Tomé López is a science writer and the editor of Mapping Ignorance

Disclaimer: Parts of this article may have been copied verbatim or almost verbatim from the referenced research paper/s.

References

- Luis A. Miccio, Paschalis Agapitos, Carlos Gamez-Perez, Francisco González, Juan Luis Suarez & Gustavo A. Schwartz (2025) Wikipedia as a cultural lens: a quantitative approach for exploring cultural networks Humanit Soc Sci Commun doi: 10.1057/s41599-025-04772-5 ↩