The potential of used cooking oil for the energy transition

The potential of used cooking oil for the energy transition

Authors: Crisbel Cardenas1, Eduardo Torre-Pascual 1,2 , Maite de Blas 1,2 , Estíbaliz Sáez de Cámara1,2, Erlantz Lizundia1,3 & Ion Agirre-Arisketa1,2

1 Repsol Foundation Classroom on Energy Transition & Circular Economy. Bilbao School of Engineering. University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU). Bilbao. España

2 Chemical and Environmental Engineering Department. Bilbao School of Engineering. University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU). Bilbao. España

3 Department of Graphic Design and Engineering Projects. Bilbao School of Engineering. University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU). Bilbao. España

In Europe, road transport originates nearly one fifth of total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (European Environment Agency, 2023). In this scenario, moving towards more sustainable fuels is particularly important in sectors where electrification remains challenging, such as heavy-duty transport. Biofuels are often considered climate neutral, as the carbon dioxide released during combustion is part of the natural carbon cycle (IPCC, 2006) and can therefore play a crucial role in the defosilization of transport.

In recent years, used cooking oil, which can contaminate up to 1,000 liters of water if improperly disposed of (MITECO, 2025), has emerged as a relevant feedstock for biofuel production. Today, more than 35% of European biofuels are produced from waste oils, driven by policies such as Spanish National Integrated Energy and Climate Plan (PNIEC) and the Renewable Energy Directive (RED II). In this context, used cooking oil (UCO) has become an attractive feedstock for renewable fuel production. This is due to its wide availability and its compatibility with existing industrial processes, which allow its chemical transformation into UCOME (used cooking oil methyl ester).

To shed more light on the actual impacts originating from the utilization of used cooking oil for energy purposes, the present study compares this process to another well-known biodiesel production process: the hydrogenation of vegetable oils (HVO). Although both processes rely on similar waste streams, they are not necessarily equivalent in terms of sustainability. In addition, conventional fossil-based diesel production was included as a reference scenario. The comparison of three of the processes has been conducted using the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) methodology.

The journey of used cooking oil

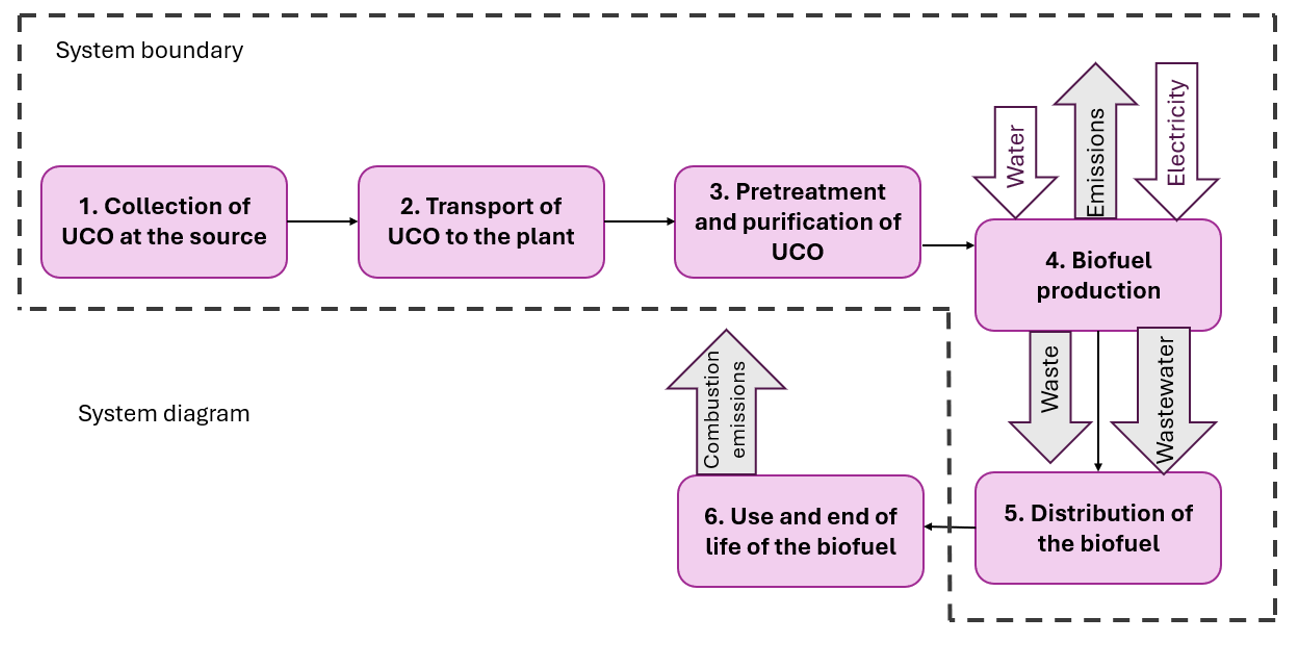

UCO can be converted into biofuels such as UCOME, a biodiesel derived from the chemical transformation of used cooking oil, and HVO (hydrotreated vegetable oil), a renewable diesel produced through the hydrogenation of oils. Figure 1 provides an overview of the full lifecycle of UCO, tracing its path from household waste collection to biodiesel production and distribution. This complete pathway represents the life cycle of the fuel and forms the basis of the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), which evaluates the environmental impacts associated with each stage of the process.

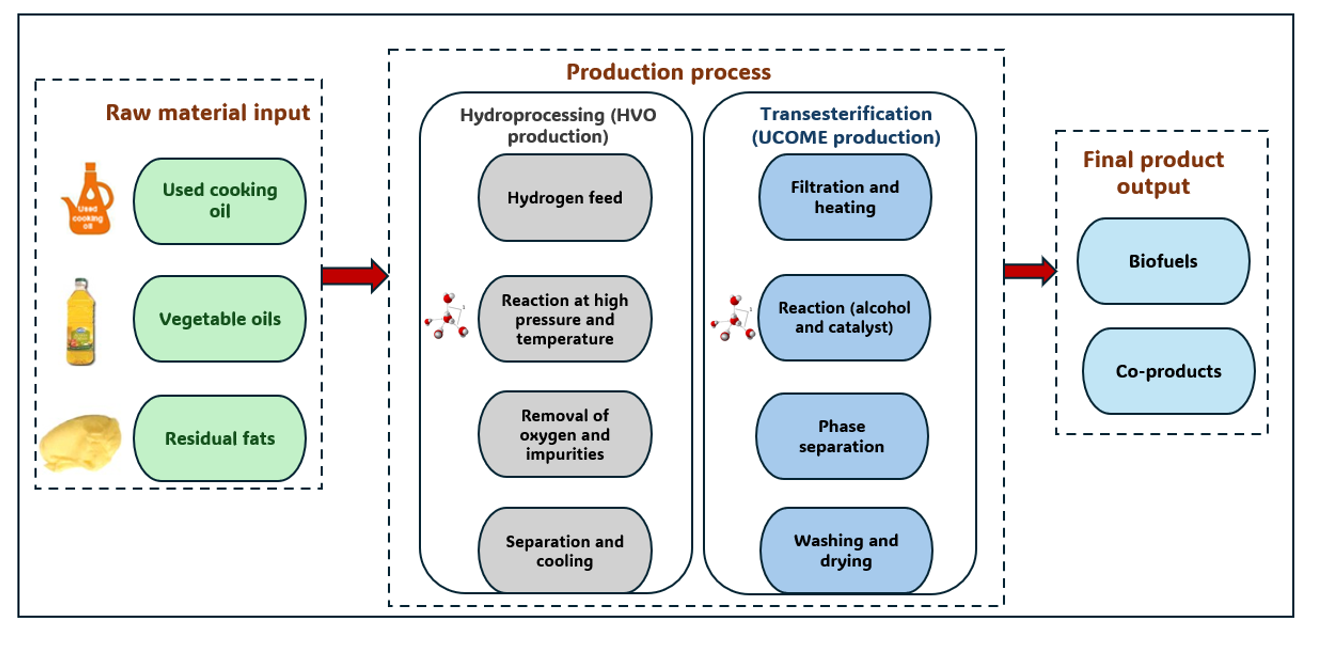

One of the most widely used biofuels is UCOME, whose carbon footprint can be reduced by more than 70% compared to conventional fossil diesel when a well to wheel perspective is considered, corresponding to values of approximately 0.025–0.030 kg CO₂-eq/MJ (JEC, 2020). Another alternative is HVO, whose climate impact largely depends on the origin of the hydrogen used in the production process. Figure 2 compares the two main technological routes for biofuel production hydroprocessing (for HVO) and transesterification (for UCOME) highlighting their key processing steps, main inputs, and resulting products.

From waste to a national resource

Used cooking oil is an abundant resource in Spain. If fully recovered, this resource could be converted into approximately 147,000 tonnes of UCOME per year. These potential highlights the strategic role that waste derived feedstocks could play in the decarbonization of the transport sector, by turning a domestic waste stream into a valuable energy resource.

Environmental traffic light

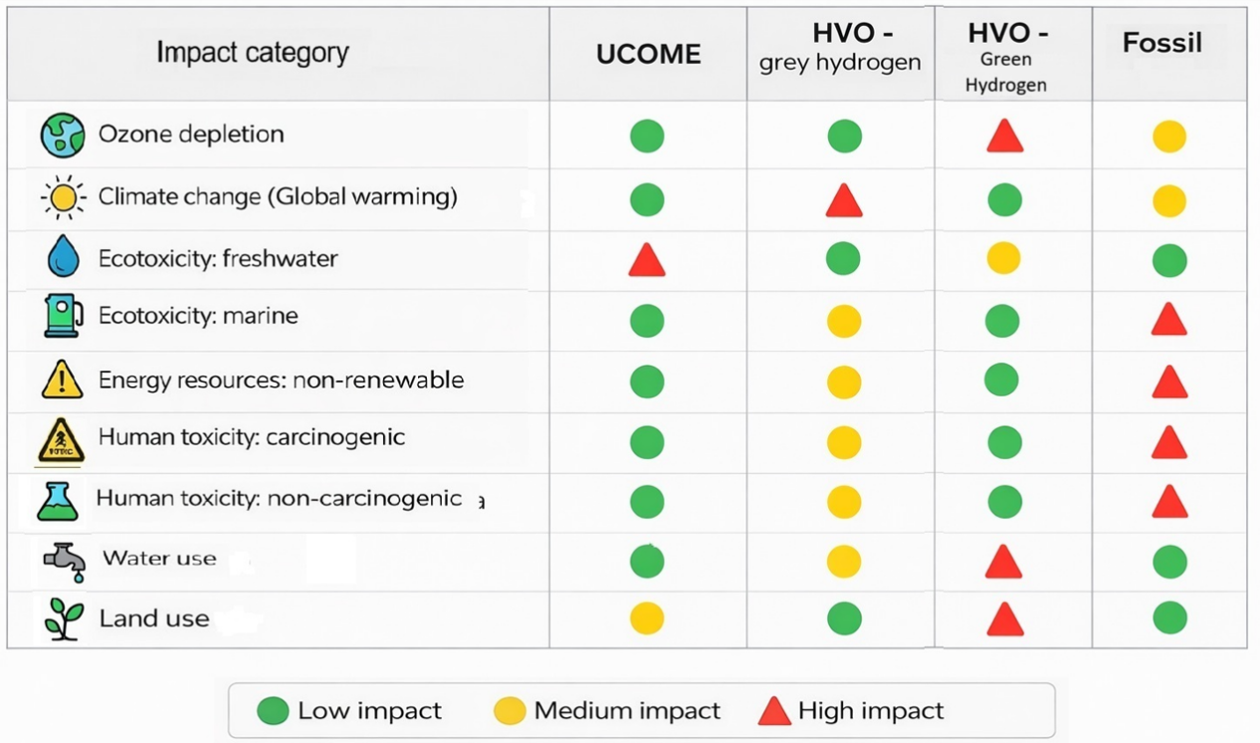

Assessing the sustainability of biofuels requires going beyond a single indicator. While greenhouse gas emissions are often the focus, other environmental dimensions such as impacts on ecosystems, human health, water consumption, and land use also play a relevant role. To capture this complexity, Figure 3 summarizes the environmental performance of the different fuel options using a color-based traffic light system, allowing for a rapid and intuitive comparison across multiple impact categories.

Based on the life cycle assessment performed in this study, considering a system boundary from the collection of used cooking oil to biofuel distribution (stages 1 to 5 in Figure 1), UCOME shows a substantially lower climate impact than conventional fossil diesel when expressed per unit of delivered energy. In quantitative terms, greenhouse gas emissions decrease from approximately 0.023 kg CO₂-eq/MJ for fossil diesel to about 0.011 kg CO₂-eq/MJ for UCOME, corresponding to a reduction of around 53% during the fuel production stage.

Beyond climate change, the environmental traffic light reveals important differences among the fuel pathways. Overall, UCOME emerges as the most favorable option, showing a consistently low environmental impact across the majority of the assessed categories. In contrast, the environmental profile of HVO strongly depends on the origin of the hydrogen used in its production. When fossil-based (grey) hydrogen is employed, HVO can display environmental impacts similar to those of fossil diesel. The use of renewable (green) hydrogen improves its climate performance but is associated with higher pressures on other environmental dimensions, particularly water consumption and land use, linked to renewable electricity generation and hydrogen production infrastructure.

Taken together, these results show that different fuel pathways involve trade-offs across environmental dimensions, as improvements in one area may be accompanied by higher impacts in others. The environmental traffic light therefore highlights the importance of adopting a multi-criteria perspective when evaluating biofuels, helping to identify the most balanced options as well as the key trade-offs involved in their deployment.

Implications for the energy transition

Advancing the energy transition requires looking beyond CO₂ emissions alone. All fuels generate environmental impacts throughout their life cycle, highlighting the importance of considering the full range of environmental effects when discussing sustainable fuels. This approach helps to identify advantages and tradeoffs across different environmental categories. From this perspective, both UCOME and HVO produced with green hydrogen show a better overall environmental performance than fossil-based diesel. This highlights that there is no single, universal solution and that sustainability must be assessed on a case-by-case basis.

Future research could further refine these conclusions by extending the system boundaries to include the use phase of fuels and by exploring alternative assumptions regarding hydrogen production pathways and energy mixes.

Beyond the specific results presented here, the case of used cooking oil illustrates a broader lesson for the energy transition. Turning everyday waste into valuable resources requires not only technological solutions, but also careful environmental assessment to avoid shifting impacts from one area to another. Tools such as Life Cycle Assessment help reveal these trade-offs and support more informed decisions. As societies move towards more sustainable energy systems, combining waste valorization with a comprehensive evaluation of environmental impacts will be essential to ensure that well intended solutions truly contribute to long term sustainability.

References

Asociación Española de Normalización (UNE). (2018). UNE-EN ISO 14044:2006/A1. Gestión ambiental. Evaluación del ciclo de vida. Requisitos y directrices. Modificación 1 (ISO 14044:2006/Amd 1:2017).

Asociación Española de Normalización (UNE). (2021). UNE-EN ISO 14040:2006/A1. Gestión ambiental. Análisis del ciclo de vida. Principios y marco de referencia. Modificación 1 (ISO 14040:2006/Amd 1:2020) (Versión corregida, enero 2022).

Bezergianni, S., Dimitriadis, A., & Chrysikou, L. P. (2013). Quality and sustainability comparison of one- vs. two-step catalytic hydroprocessing of waste cooking oil. Fuel, 118, 300. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2013.10.078

Cardenas, C. (2025). Valorización de aceites de cocina usados para la producción de biocombustibles sostenibles: comparación de tecnologías mediante análisis de ciclo de vida. Trabajo Fin de Máster, Universidad del País Vasco UPV/EHU.

Ecoinvent Association. (2024). ecoinvent database. Disponible en https://ecoinvent.org/database

Eurostat (2025). Glossary: Biofuels. Disponible en: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Glossary:Biofuels

European Environment Agency. (2023). Greenhouse gas emissions from transport in Europe. EEA Report.

IPCC. (2006). 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories. Volume 2: Energy. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

JRC, EUCAR & Concawe. (2020). JEC Well-to-Wheels Report v5: Well-to-Tank (WTT) report version 5. EUR 30284 EN. Publications Office of the European Union. doi:10.2760/100379.

Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico, MITECO. (2025). Obtenido de: https://www.miteco.gob.es/es/calidad-y-evaluacion-ambiental/temas/prevencion-y-gestion-residuos/flujos/domesticos/fracciones/aceites-cocina.html

Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico, MITECO. (2025a). Estadísticas de biocarburantes. Recuperado el 6 de febrero de 2025, de https://www.miteco.gob.es/es/energia/hidrocarburos-nuevos-combustibles/biocarburantes/estadisticas.html

Shahid, E. M., & Jamal, Y. (2011). Production of biodiesel: A technical review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 15(9), 4732–4745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2011.07.079