Antimicrobial peptides let ions through membranes without boring holes

Antimicrobial peptides let ions through membranes without boring holes

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are highly potent and broad-spectrum antibiotics, found as components of the innate immune system in almost all forms of life. AMPs are short proteins, tiny compared with conventional antibiotics but extraordinarily effective: they bind to and disrupt bacterial membranes, which quickly incapacitates or kills a cell. For decades, the picture many scientists worked with was simple and intuitive: peptides insert into the membrane and make a pore, a stable hole through which ions and other small molecules leak. That simple picture has driven thinking about both how AMPs work and how to design peptide-based antibiotics.

A new study 1, however, challenges that tidy narrative. Using time-resolved structural measurements and careful reanalysis of molecular simulations, researchers show that several natural AMPs can cause very fast ion permeation without forming long-lived, well-structured transmembrane pores. Instead, the peptides act from the membrane surface and trigger short-lived, water-filled channels that conduct ions briefly but effectively. The upshot is a dynamical mechanism (transient water channels produced by accelerated lipid movement) that explains fast ion equilibration across membranes without the need for stable, protein-lined holes.

A pore, what else?

The basic structure of a biological membrane is a bilayer of lipid molecules, each with a hydrophilic head and a hydrophobic tail. The two leaflets of the bilayer face outward and inward. If you imagine poking a small, stable hole through both leaflets, that would be a classical pore: a well-defined structural defect that stays open and lets ions and molecules cross continuously. Many experiments and models have supported such pore formation in various conditions, but direct, time-resolved evidence that stable pores are required for ion flux has been scarce.

TR-SAXS

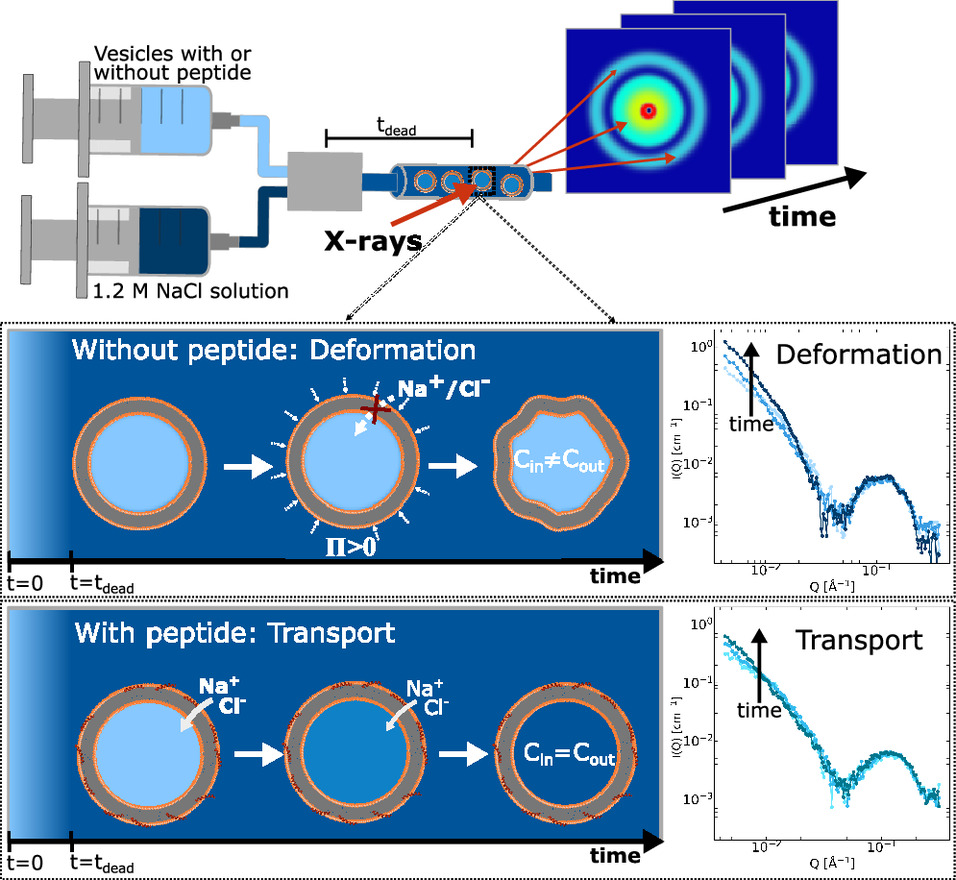

The team approached the problem with a method called time-resolved small-angle X-ray scattering (TR-SAXS). SAXS detects changes in the way X-rays scatter from a sample and is sensitive to nanoscale structural features such as vesicle size, membrane thickness, and domain organization. Making it time-resolved means the authors could follow structural changes and ion movement on millisecond timescales while peptides interacted with lipid vesicles. In parallel, they examined previously reported all-atom molecular dynamics simulations to see what kinds of transient events the peptide–membrane system was undergoing.

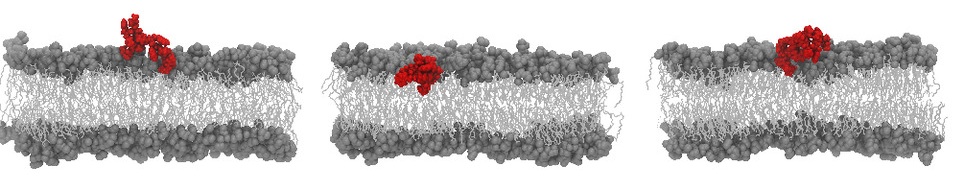

Largely peripheral

What they observed was striking. When peptides such as indolicidin bound to vesicles, salt concentrations inside and outside the vesicles equilibrated in a few tens of milliseconds. This is very fast, and fast enough to matter physiologically. Yet the SAXS data showed that the peptides remained largely peripheral, lodged in the outer leaflet rather than threading through the bilayer. The scattering patterns also lacked signatures expected for ensembles of long-lived, transmembrane peptide pores. Those two facts together argue against the idea that stable, structural pores are the main route for ion flow in these experiments.

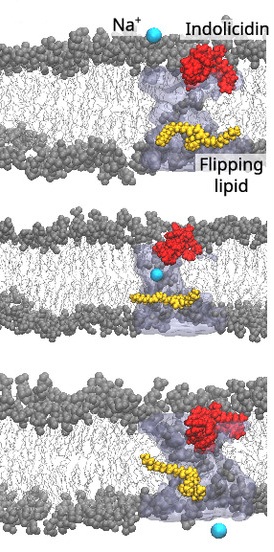

Local flip-flop events

So how can ions cross so quickly if there are no permanent holes? The authors’ interpretation brings lipid dynamics into the foreground. Lipid flip-flop (the movement of lipid molecules from one leaflet to the other) is usually rare and slow because it requires an unfavorable motion of a polar head group through the hydrophobic core. The researchers show, however, that peripheral peptide binding can accelerate local flip-flop events. When a lipid flips, it can transiently carry water molecules with it, or it can destabilize the local packing so that a brief, water-filled channel forms between the two leaflets. These channels are fleeting: they exist for very short intervals but occur often enough and at the right places to allow ions to pass, producing the rapid salt equilibration seen in the experiments. Reanalyzing molecular dynamics snapshots supports precisely this picture of short-lived, ion-conducting water pathways rather than continuous protein-lined pores.

Practical implications

The results have a few practical implications. First, they reconcile two kinds of evidence that were previously in tension: experiments showing fast membrane permeabilization and simulations that rarely produced stable pore structures. Second, they shift attention toward membrane dynamics and lipid mobility as central variables in antimicrobial action, not just the static structural arrangement of peptides. That matters if one wants to design peptides that are potent against bacteria but less damaging to host cells: tuning how a peptide affects lipid packing and flip-flop could be a finer way to control selectivity than simply aiming for pore formation. The research community has already noticed other surprising behaviors (for example, domain, or “patch”, growth in membranes when AMPs bind) and those mesoscopic effects likely tie into the mechanism described here.

A few caveats

The experiments were performed with model lipid vesicles under controlled conditions; bacterial membranes are more complex, with proteins and varied lipid chemistries that could modify the balance between transient and stable mechanisms. Also, not every AMP behaves the same way: concentration, sequence, and membrane composition will influence whether transient channels or more permanent disruptions dominate. The paper’s strength is that it combines direct, time-resolved structural measurements with simulation reanalysis to make a consistent argument; the next steps will be to extend those observations to more realistic membranes and to quantify how sequence features map to dynamical outcomes.

A refined view

These results mean that we need to think of antimicrobial peptides as agents that shake the membrane just enough to let water and ions slip through fleeting cracks, rather than drilling permanent tunnels. Those fleeting cracks, multiplied across a bacterial surface and synchronized in time, can be an efficient way to depolarize and kill a cell. This refined view is not merely a detail; it changes where researchers will look when they try to understand resistance, toxicity, and the rational design of peptide therapeutics.

Author: César Tomé López is a science writer and the editor of Mapping Ignorance

Disclaimer: Parts of this article may have been copied verbatim or almost verbatim from the referenced research paper/s.

References

- V.R. Koynarev, M.L. Nader, K.K. Almåsvold, H.M. Cezar, T. Narayanan, L. Porcar, M. Cascella, & R. Lund (2025) Structural pores not required: Antimicrobial peptides induce ion permeabilization of lipid membranes through transient water channels Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2517944122 ↩